Dante J. Pieramici, MD: The COVID-19 pandemic has been an experiment in nature, not only for the coronavirus but for the impact it’s had on other medical conditions. Early in the pandemic, patients, particularly at-risk patients, were afraid to go out and were under lockdown in many institutions, resulting in missed appointments and delayed or interrupted treatments.

This discussion focuses on the impact of delayed treatments on the visual outcomes of various retinal diseases, specifically neovascular AMD, diabetic macular edema (DME), and macular edema associated with retinal vein occlusions (RVOs).

Dr. Singh, what was the impact of COVID-19 on the number of patients coming in to your large academic center for intravitreal injections?

Rishi P. Singh, MD: Initially, we saw a significant drop in volume, close to 30% or 40%. Even patients receiving active injections didn’t return for a month because they didn’t know what to make of the pandemic.

When we realized this was happening, we took steps to educate people in our communities about the need for perpetual anti-VEGF therapy. We finally saw patients return, and it was striking to see what the return was like. In fact, my colleagues and I undertook a chart review to determine what missing a single injection meant for patients.1

We found that visual acuity declined by 5 or 6 letters, particularly in patients with high VEGF-related diseases, such as DME and RVO, and those visual acuity losses persisted 9 months after that one missed injection.

That was a stark reminder that perpetual treatment is necessary, and that we clearly have an issue with drug durability. As our patients return for treatment, we’re making sure that we continue to educate them on why those injections are necessary.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Wykoff, what was your experience in the large private practice where you work?

Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD: Our experience was similar, but with some subtle differences. At the peak of the decline, our volume dropped about 20% to 25%. Then very rapidly, we saw an increase in volume in our clinics, because the general ophthalmologists around us were shutting down completely, and we were getting many of the peripheral retina cases that they had been managing. As a result, we had quite a high census of patients in many of our clinics relatively early on during the lockdown.

Overall, my experiences have been heterogeneous. I believe they echo our incomplete understanding of these disease processes. While some patients absolutely lost vision, others did fine while they were away for a number of months. This just underscores the challenges we face. When patients come back and they’ve lost vision, it’s an easy discussion. They know what happened, we know what happened, and we start to treat them again. But when a patient I was treating for DME returns and the DME hasn’t recurred, I start to wonder if I need to treat this patient as frequently as I had been. I’ve had many discussions like that, particularly with patients who have wet AMD. My response to them has been, “I think we dodged a bullet here with a few months of undertreatment, but that’s not my recommendation going forward. Based on all of the data we have over the last decade, I think consistent dosing overall achieves the best long-term visual and anatomic outcomes.” In the vast majority of those cases, I have restarted treatment, in some cases with a decreased frequency of dosing.

Dr. Singh: Some of the changes we made in our practice have streamlined our care. We moved the OCT to the lane where we see patients, and we omitted imaging whenever possible. My thought process was: If a patient was on a good treat-and-extend regimen on a quarterly interval and vision hadn’t changed, was an image going to help me make another clinical decision? I’m not sure. Many of us omitted imaging for those patients during that timeframe and opted not to get additional fluorescein angiograms, for example, in a solid case of neovascular AMD. We’d just treat the patient right away. From that standpoint, we streamlined our practice as much as we possibly could, although, admittedly, obtaining fewer images during that time may have come at the cost of understanding some nuances of the disease.

Dr. Pieramici: Many of our modifications made the clinic safer for patients and made the visits quicker. When patients saw that we were getting them in and out quickly and that we were taking all recommended precautions, I think they were comfortable returning for their next scheduled visit. As we all engaged in this experiment in nature, we were pushed to our limits to try to function efficiently. We realized that we probably don’t need fluorescein angiograms or OCTs at every visit. We can monitor patients in a more basic way and still end up with a good outcome.

New Challenges After Treatment Lapses

Dr. Pieramici: We did see variability in disease status when patients returned to our clinic. Some patients lost vision, and we’ve been fighting to get that vision back. In some cases of DME or vein occlusion, patients seemed to have improved, but some AMD patients lost vision that I think we’re not going to get back.

Dr. Wykoff, do you think any differently now about fluid in the eye? How do you approach certain patients, based on what you’ve learned during the pandemic, particularly when treatment is interrupted?

Dr. Wykoff: What we saw during the pandemic highlighted two major shortcomings of our current practice situation. One is the challenge we face in predicting the ideal treatment frequency—and when that treatment frequency should change—for an individual patient for the medium term and the long term. Some people are high anti-VEGF-need patients for a time, and then we may be able to decrease their treatment frequency over time. But we’re not good at knowing when that transition occurs. We don’t have any biomarkers for the VEGF loads in people’s eyes on a regular basis. So the pandemic brought to my attention the challenges of our ability to prognosticate on an individual patient basis.

The other shortcoming that the pandemic brought out is the need for more durable treatments. Our current treatments are effective, but we need new, more durable medicines or devices and implants that can extend the durability of the medicines we have today. Related to that, I believe home monitoring would be ideal. We are such an imaging-heavy field, to be able to monitor patients remotely with imaging would be fantastic.

It’s interesting to hear that you decreased imaging frequency, Dr. Singh. If anything, I became more dependent on imaging, because I was decreasing our examinations to avoid close contact with patients. We did very few fluorescein angiograms, but we increased our Optos imaging, because I felt it was safer for patients than a comprehensive, dilated examination.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Singh, did you change any of your treatment strategies during the pandemic?

Dr. Singh: During the pandemic, four different anti-VEGF agents—three FDA-approved and one off-label—were available to us. In most of our practice scenarios, we were advised to use the off-label drug whenever possible and then potentially an on-label drug. Our preference among the on-label drugs was one with a better drying effect, but at the time, the one with the better drying effect also had intraocular inflammation issues. So, we often avoided that drug and chose the most durable agent, because we thought we’d be able to extend faster.

Based on data from the ALTAIR and ARIES trials, which had been released just prior to the pandemic, that drug was aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron).2,3 Good data from those trials suggest that we can extend our treatment interval to 8 weeks and potentially beyond. Thus, we had Level 1 evidence supporting our use of Eylea as our primary therapy for many patients. Knowing that we wouldn’t see adverse issues, such as intraocular inflammation, retinal vasculitis, or lack of durability, we ended up switching many patients to Eylea and starting many others with Eylea.

Dr. Pieramici: Did data from those trials give you confidence that many patients can be extended out to 12 weeks and in some cases beyond using Eylea?

Dr. Singh: The ARIES and ALTAIR data solidified that for me. Seeing large percentages of patients go 12 weeks and beyond in those studies was reassuring. In addition, both studies had 2-year data points, and both of them looked really good as far as durability and low rates of side effects, which I think is important in this time period.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Wykoff, did you change either your strategy or drugs during this time?

Dr. Wykoff: In general, my goal with or without a pandemic is to keep the macula as dry as possible for as long as possible between injections. I don’t have a drive to start with an off-label agent as many physicians do, so I often gravitate toward ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) or Eylea first line. In my experience in many cases, Eylea proves to be a better drying agent, consistent with the comparative data that we have, particularly in DME.4

I am intolerant of fluid, and this is a challenging landscape. Trials, such as FLUID,5 and even ARIES and ALTAIR, bring up the topics of how much fluid matters and if we can extend longer, even if there’s persistent fluid, but I think there’s risk.

Looking at ARIES and ALTAIR, I do see a decrease in visual acuity in some cases, particularly through the second year, so I worry that patients are being extended too far. I use OCT guidance to dictate what that interval is. I don’t have a problem maintaining patients on a monthly dosing schedule. While VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 are somewhat dated now, a post hoc analysis by Jaffe and colleagues showed that a meaningful proportion of patients treated with Eylea probably benefit from monthly dosing.6

I’m a big believer in finding the individual patients who need more frequent dosing and treating them as frequently as possible. I’m not a believer in one-size-fits-all with any of these diseases. I don’t hesitate to maintain a monthly dosing schedule, but if a macula is completely dry, I’ll absolutely push it to Q8, Q12, and Q16. It’s nice to have prospective data, such as ARIES and ALTAIR, that support taking patients out to even 4 months with Eylea in many cases.

Role of Fluid in AMD, DME, RVO

Dr. Pieramici: We’re discussing a variety of diseases—neovascular AMD, DME, and RVO with macular edema. Do you think about fluid the same way in these diseases?

Dr. Wykoff: We still have a lot to learn about the nuances of fluid in each of these disease states. In AMD, for example, a tremendous amount of data tells us that, from a prognostic perspective, intraretinal fluid correlates with longer-term worse outcomes than subretinal fluid, but that doesn’t mean subretinal fluid is good. The FLUID study helped us understand fluid status, but I think sometimes that trial has been oversimplified to suggest that subretinal fluid can be observed. The FLUID study was a treat-and-extend study for all patients and there was simply more leeway in the interval for patients with only subretinal fluid without intraretinal fluid.

The other finding from the FLUID study was that as you tolerated more subretinal fluid, you actually got more intraretinal fluid. The problem is we can’t choose intraretinal fluid versus subretinal fluid. The patient has what the patient has, and we have to focus on maintaining as stable and dry a retina as possible.

The other factor related to wet AMD that’s become more important to me than the absolute amount of fluid is the fluid fluctuation status over time. Chakravarthy and others have shown repeatedly that we want to avoid these fluctuations, that maybe a little bit of fluid that’s stable over time will be better tolerated than fluctuations.7

I definitely do tolerate more fluid in DME. Protocol V highlights the fact that we can tolerate some central fluid as long as we monitor these patients carefully.8

RVO tends to be an on or off disease where there’s either a lot of fluid or it’s dry. So usually, you want to find your interval and then maintain a dry retina by going just under the interval when you see recurrence.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Wykoff is strict with fluid. He fears the fluid, particularly in neovascular AMD. Dr. Singh, are you somewhat less strict? Are you more comfortable with fluid?

Dr. Singh: I think the bottom line is that all of the studies we talk about, except perhaps the FLUID study, took into account how the fluid was responding and then framed their treatment guidelines based upon that. In many studies that have analyzed fluid changes and fluid presence over time—HARBOR, CATT, VIEW 1, and VIEW 2—what we’re really seeing is that fluid is just a biomarker that is present or absent.9-11 It doesn’t mean we weren’t treating for it. It just happened to be a positive or negative biomarker, depending on the situation.

In putting together some information for an upcoming talk, I’ve concluded that monitoring central subfield thickness (CST) is probably too simplistic. For a long time, we thought we could look at CST because we can’t quantify fluid right now through artificial intelligence; however, CST correlates poorly with fluid levels. It’s probably a poor biomarker, but it’s the best one we have right now.

With regard to fluid concerns, I agree that intraretinal fluid is definitely what we’re most concerned about. I think the jury is still out about subretinal fluid. I believe we don’t have enough data to suggest that subretinal fluid is either equivocal or positive or negative. I think all fluid essentially has some value to us.

Dr. Pieramici: I would agree. All fluid is not the same, whether it’s a good thing or just not a bad thing. I think it does allow us to extend treatment intervals in certain circumstances for some patients, even though they have some stable subretinal fluid. In a patient with diabetic macular edema, however, it’s unclear to me. There’s a modest correlation between changes in fluid and visual acuity. So the anti-VEGF agents in these diabetic patients may be doing more than just helping the fluid on some level. Therefore, I’m much more tolerant, and I think it’s much less of an acute situation in these diabetic patients.

A New Look at Pre-Pandemic Data

Dr. Singh: Some of the data that might be helpful to us is from before the pandemic. My colleagues and I studied patients who had 3- or 4-month lapses of treatment with any of the anti-VEGF agents across various disease states to see if there were any differences.12 In the AMD arm, it was clear that there was a detriment, even at 3 months of delaying therapy. In the DME and the RVO arms, essentially it was equivocal by 1 year of restarting therapy and integrating these patients back into the mix of things.

That being said, the OCTs showed thickening, and they all had fluid; visual acuities were remarkably similar to what they were if they’d never had this delay. We had a control population that we monitored through a matching process. This is a short-term paper, studying only 3 months of a delay in a 1-year follow up. What is the effect over a 2-, 3-, or 4-year period? All I can tell you is their anatomy is very different than what we would expect it to be in these cases.

Dr. Wykoff: We do have data from waiting 6 months to treat. In the VIVID and VISTA trials, patients had center-involved fluid with vision loss.13 Some of the patients were randomly assigned to an observation arm, and when they lost vision beginning at 6 months, they were allowed to transition over and receive Eylea. Those patients did well. They gained vision. But they never gained as much vision as the patients who were treated in the beginning of the trials. So I think we do have good prospective registration trial data to show that waiting 6 months in patients with center-involved fluid with vision loss is not good for long-term outcomes.

My second point has to do with Protocol V, a fascinating and controversial paper.8 Unfortunately, I believe it’s been over-interpreted to suggest that patients can be observed if they have good vision. The problem is the vision in those eyes was really good. It wasn’t symptom-based for patients. Their best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) had to be 20/25 or better. It was so strict because we have good data that patients with BCVA of 20/32 or worse will do better if they receive prompt treatment. Thus, we have to be careful in practice to not over-interpret Protocol V and apply it to patients who were not included in the study. It really only applies to patients who have absolutely normal visual function.

Dr. Pieramici: In addition, you must monitor patients closely and be comfortable that you can measure a difference on a Snellen visual acuity chart. In clinical practice, I think we’re less comfortable with the visual acuities we get on Snellen than in a clinical trial. Being able to tell if visual acuity is worsening and know when to switch treatment may be difficult.

Dr. Wykoff: To that point, the PANORAMA data helps guide what I do.14 While I enjoy looking at the Protocol V data, that’s not how I practice. If patients have center-involved fluid with excellent vision, I’ll often apply the PANORAMA treatment protocol, whereby I treat them initially and then quickly go to 12- or 16-week intervals. To me, PANORAMA is more applicable, because it’s looking at a population of patients who have good vision and yet they have diabetic retinopathy. We have very good data through 2 years from PANORAMA, showing that patients can do quite well when maintained with just three injections a year.

Dr. Singh: I agree. I think this idea of treating diabetic retinopathy, particularly in patients who have severe nonproliferative disease who were studied in PANORAMA, is our opportunity as retina specialists. In all of medicine, there are very few conditions for which we can say we can regress a disease state, or we can at least cause it to get to a lower level compared to what it was. What we’re seeing in diabetic retinopathy is quite remarkable. We’re causing remodeling of the blood vessels so that reabsorption of that blood occurs.

It’s interesting to see that, because I think it tells us that we’re going to potentially prevent patients from experiencing socioeconomic losses from their condition. Vision-threatening retinopathy complications are far lower. With the amazing amount of durability exhibited in PANORAMA—almost quarterly injections—we could enable patients to continue to do their work and prevent them from losing their jobs. Some of these medications can be transformative by keeping patients in the working population.

Dr. Wykoff: I believe these drugs have multiple effects, and we’re still learning about some of the most interesting effects of them. One is on the retinal vasculature itself. I think the Holy Grail of treatment for diabetic retinopathy is to slow and maybe one day reverse areas of retinal nonperfusion. I don’t think our current drugs reverse it, but I think we have fairly good data now that they can meaningfully slow the worsening of these areas of retinal nonperfusion, as was demonstrated for Eylea in VISTA and VIVID, and for Lucentis in RISE and RIDE, and there were hints of it in PANORAMA, as well.13-15

I believe the underlying vasculature is our core target, and we’re seeing the secondary effects of a breakdown of the vasculature through the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale. When we’re treating, we’re not treating the dot-blot hemorrhages. Even though the hemorrhages resolve, that’s a secondary effect. What I’m trying to impact is the underlying retinal vasculature, and you can’t see that on a color fundus photograph.

Dr. Pieramici: That’s the gold mine really. Diabetes is a vascular disease, but we can’t yet stop or reverse the vascular damage. With anti-VEGF agents, we can slow the progression of vascular damage and loss.

Eylea’s Place in the Treatment Regimen

Dr. Pieramici: Considering we have several anti-VEGF agents, how does Eylea fit into your treatment regimen for patients with neovascular AMD, DME, and RVO with macular edema?

Dr. Singh: Eylea fits very nicely into my regimen, particularly for RVO. To me, the data from LEAVO has been the most impactful of any study I’ve seen in the past couple of years.16 Seeing the data on the drying effect through other studies but also through LEAVO exploring the superiority of the drug in comparison to the non-branded agent is important. That study has also resonated with the idea that RVO patients are the most difficult to take care of because they’re either on or they’re off, and when they’re off, they’re really off the rails sometimes. They have significant macular edema and poor vision. They can lose vision, and neovascular glaucoma and vision-threatening complications can occur. Therefore, I want to maintain these patients on the best possible agent with the most efficacy. In addition, the fact that Eylea inhibits placental growth factor (PlGF), which is upregulated in these ischemic retinopathy conditions, is another reason why I use it to treat RVO.

For DME, we have Level 1 evidence from multiple studies, including Protocol T, that have shown incredible benefits of Eylea, particularly in patients who have poor vision.17 Even in patients who have good vision—20/40 or better—there were some differences with regard to their absolute vision gain, particularly those who had CST greater than 320 µm or 350 µm. That’s an important concept. This is for patients who have true DME with morphological states and even good vision potentially. This is a very good drug for them, because you can see significant differences with regard to gains in visual acuity. I think people forget about the substudy from Protocol V, but it’s relevant and important to our patients, because it might be the difference between gaining 10 letters of visual acuity versus gaining only 3 or 4 letters and just chalking it up to the fact that their visual acuity is 20/40 or better.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Wykoff, how does Eylea fit into your practice?

Dr. Wykoff: RVO and DME are where we have the strongest data that separates Eylea from the other anti-VEGF agents. To LEAVO, I would also add a small study called NEWTON and even SCORE 2.18,19 All of these studies point toward Eylea as a more durable agent, because it has a better drying effect. There are many arguments for why that might be, but clinically, I think we have quite a bit of prospective data to support it.

The same with diabetic retinopathy and DME. I think the data from PANORAMA is quite convincing, and the DRCR Protocol W supports it.14,20

While I think Lucentis is effective for diabetic retinopathy and DME, we don’t have data specifically looking at the population of patients who have proliferative diabetic retinopathy without DME. It’s helpful to be able to guide management when we have prospective trials, multiples of them, to guide which drug to use.

Protocol T continues to influence my clinical practice, because I find Eylea to be the optimal drying agent, particularly in DME. In neovascular AMD, all of the agents are similar, but when we’re looking at durability and getting the longest interval possible, I think the data for DME and RVO plays out in neovascular AMD as well.

Dr. Pieramici: I think when you have a tough case, you’re going to reach for Eylea or you’re going to end up there. You may start with off-label bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech) and go down the list, and Eylea is at the end of it. But why not use it at the beginning, if you can? In my opinion, if it’s the best agent for the tough cases, it’s going to be as good or better or more durable for the easier cases.

Let’s continue with a discussion of some real-world cases and the impact of treatment interruption on specific disease states.

CASE REPORT:

Effect of Treatment Lapse for CRVO with Macular Edema

Dr. Singh: This 76-year-old man presented with worsening vision in the left eye for several months. He had no history of ocular surgeries, procedures, or injections. He had been diagnosed with CRVO with macular edema in the left eye and had been referred to me for management in my clinic.

Initial evaluation reveals some subtle edema, indicating a nonischemic vein occlusion, and the B-scan shows subretinal fluid (Figure 1). Retinal thickness was 383 μm. ETDRS acuity was 76 letters, or roughly 20/40 on the Snellen chart.

After 3 monthly anti-VEGF injections (our typical loading dose), the patient’s visual acuity was 80 ETDRS letters. There was no evidence of significant fluid, and retinal thickness had normalized at 297 μm.

The data for treat-and-extend has not been solidified in RVO, but sometimes when nonischemic vein occlusions are treated, they may reperfuse and patients may not require ongoing therapy. After the third injection, this patient’s visual acuity and OCT had improved, and we opted to withhold therapy and scheduled the patient for follow-up in 1 month. He returned 3 months later.

Figure 2 shows the status of the left eye 3 months after therapy was discontinued. Retinal thickness was 837 µm with massive amounts of fluid present. Visual acuity had decreased to 45 ETDRS letters, which is just barely 20/200 on the Snellen chart.

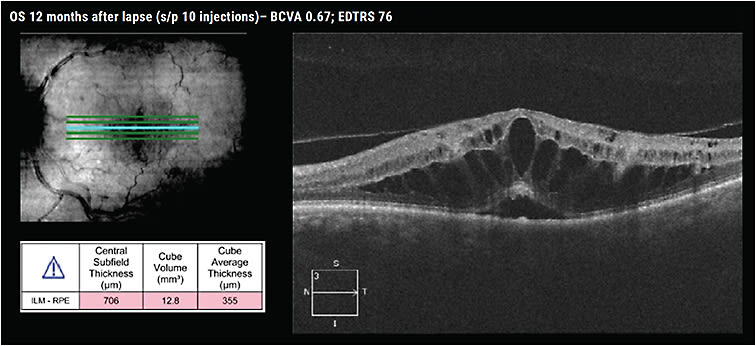

We resumed treatment and aggressively tried to regain lost ground, administering 5 injections in 6 months. Twelve months after the lapse in treatment, the patient had received 10 injections. His visual acuity was 76 ETDRS letters, almost at his baseline, but edema persisted on OCT (Figure 3).

I wanted to share this case because it’s an interesting example of the effects of a lapse in therapy akin to what we’ve seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. This case was not from the pandemic. This is a patient from a study performed at the Cleveland Clinic in which we examined how a 3-month lapse in therapy affected some patients.21

In our study, we found that patients with RVO who had an unintended lapse in treatment of 3 months experienced significant CST increases that persisted throughout 12 months of follow-up. The lapse patients experienced a significant decrease in visual acuity that persisted for 3 months of follow-up and normalized after 6 months. We also found the lapse patients required a significant increase in the number of anti-VEGF injections post-lapse, yet they still experienced negative visual outcomes.

Dr. Pieramici: Dr. Singh, what do you think is happening here pathophysiologically?

Dr. Singh: I think we’re seeing VEGF levels rise to an ischemic state, which we’d expect in ischemic RVOs. Trying to reverse that is next to impossible, regardless of the anti-VEGF agent you use. Fortunately, the visual acuity wasn’t as bad as we expected it to be, but certainly the OCT was less than desirable. I believe giving that treatment over a longer period, we probably would see some eyes return to a normal OCT state, but it will take a long time to reduce those VEGF levels, particularly in RVO, which is such a heavily VEGF-dependent condition.

CASE REPORT:

Impact of Delayed Treatment for NPDR

Dr. Wykoff: It’s always interesting to think about patients with poorly controlled blood sugar, because they’re often excluded from the prospective trials. This 56-year-old man has type 2 diabetes and nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). His HbA1c is 12.

Color fundus images show extensive hard exudates, lipids, cotton wool spots, and dot-blot hemorrhages (Figure 4). Visual acuity is 20/70 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left eye.

This patient received fairly frequent treatment with Eylea. Figure 5 (top) shows the patient’s right eye. As you can see, he did quite well after receiving the first 3 monthly injections. CST and visual acuity were improving. But then, life got in the way, as it often does for patients and their caregivers. When I saw the patient 2 months later, CST was almost twice as thick as it had been at baseline. Subretinal fluid is now extensive, as well as the presence of intraretinal fluid, and the patient noticed that his visual acuity had declined to 20/80.

Figure 5 (bottom) shows the patient’s left eye during the same treatment period. At baseline, both eyes had similar thicknesses and similar visual acuities. After 3 monthly injections, visual acuity was about the same, and CST was improving. The IS/OS junction, the ellipsoid zone, was beginning to repopulate. But then, there’s a lapse in treatment by just 1 extra month from November to January. Again, fluid increased, and visual acuity was maintained.

This is a great example of the benefit and the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy in a very high VEGF load eye. It’s clearly responsive to anti-VEGF therapy, but it continues to need regular dosing. Compliance becomes the challenge for this patient.

Dr. Pieramici: This is a sick patient with poorly controlled diabetes and what looks like severe nonpro-liferative disease. I imagine that when he first came in, he probably hadn’t had treatment and he’d had this edema for many months.

Then you gave him a few treatments and, particularly in the right eye, it seems like a rebound effect occurred after he discontinued the anti-VEGF therapy. What’s going on there?

Dr. Wykoff: It’s difficult to know. Even if you look at the CST map for the left eye, you can see the superior macula has become very thick, which does suggest some type of a rebound. This patient’s blood sugar and blood pressure are fluctuating dramatically. We’re trying to get him in to see a new primary care physician to get him back on medicines. He’s been starting and stopping his systemic medicines. I think we’re seeing a lot more going on here than just the eye condition. We’re seeing the systemic manifestations of these poorly controlled vascular diseases.

Dr. Singh: These are tough cases to manage, and I think you did the best you could for this patient. The visual acuity was flirting with 20/40 the entire time, which I think is a good thing, because potentially this patient could regain driving vision with continual therapy.

When I saw your first picture, I didn’t know if there was some hemorrhage present, and I wondered if the disease is truly proliferative in nature. Even if the disease is proliferative, we know that scatter laser doesn’t change the frequency of treatment in these patients. Even treating them for potentially proliferative disease wouldn’t have an effect on the final outcome. I think you’ve done an admirable job of keeping this patient in treatment.

Dr. Wykoff: When I see a lapse like this, if it’s proliferative or severe nonproliferative, I move forward with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP). I don’t put in complete PRP, but as soon as there’s a lapse in treatment, I’m honest with the patient. I say, “It’s in everyone’s best interest if we put in some laser, in case you can’t come back. It’s not a personal comment at all, but life gets in the way for all of us and we can prevent a bad outcome if we put in some laser.”

I often encourage patients like this to agree to peripheral scatter laser.

Dr. Pieramici: This is the type of patient I really worry about, because sometimes they come back all of a sudden a year later and they have rubeosis and their visual acuity has declined from 20/60 to counting fingers. They’re young patients, and it’s depressing for them and for us. Treating with the laser gives some security if they do disappear for a period of time.

Using Eylea to treat a patient like this is a great choice. It’s the strongest agent that we’re going to be comfortable with. Even if we have to use it every month, I feel it’s going to give him the best chance of drying and maintaining good vision.

Learning From Lapses

Dr. Pieramici: The COVID-19 pandemic has given us a natural experiment to see what happens to some of our patients when they miss their scheduled treatments. In some cases, these lapses were dramatically detrimental to their vision, while in others, patients actually did okay. I think it taught us more about treatment intervals and the importance of being consistent as much as we can. It also taught us what medications may be more effective and more reliable in certain types of patients, particularly when they may not follow up as scheduled.

Going forward, I also think we’ve learned more about fluid. We can still debate these issues, but at the end of the day, being able to monitor our patients, reduce the burden of therapy in the long run, but end up with efficacious outcomes is the end result for these patients. I think they’re going to do very well with anti-VEGF therapy. ■

REFERENCES

- Song W, Singh RP, Rachitskaya AV. The effect of delay in care among patients requiring intravitreal injections. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(10):975-980.

- Ohji M, Takahashi K, Okada AA, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept treat-and-extend regimens in exudative age-related macular degeneration: 52- and 96-week findings from ALTAIR: A randomized controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1173-1187.

- Mitchell P, Holz FG, Hykin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept using a treat-and-extend regimen for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the ARIES study: A randomized clinical trial. Retina. 2021;41(9):1911-1920.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203.

- Guymer RH, Markey CM, McAllister IL, et al. Tolerating subretinal fluid in neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with ranibizumab using a treat-and-extend regimen: FLUID study 24-month results. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):723-734.

- Jaffe GJ, Kaiser PK, Thompson D, et al. Differential response to anti-VEGF regimens in age-related macular degeneration patients with early persistent retinal fluid. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(9):1856-1864.

- Chakravarthy U, Havilio M, Syntosi A, et al. Impact of macular fluid volume fluctuations on visual acuity during anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with nAMD. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(11):2983-2990.

- Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1880-1894.

- Ho AC, Busbee BG, Regillo CD, et al. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2181-2192.

- Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group, Maguire MG, Martin DF, et al. Five-year outcomes with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: The comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(8):1751-1761.

- Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2537-2548. [published correction appears in Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):209-210].

- Yalamanchili SP, Maatouk CM, Enwere DU, et al. The short-term effect of a single lapse in anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema within routine clinical practice. Am J of Ophthalmol. 2020;219:215-221.

- Heier JS, Korobelnik JF, Brown DM, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 148-week results from the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(11):2376-2385.

- Brown DM, Wykoff CC, Boyer D, et al. Evaluation of intravitreal aflibercept for the treatment of severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: Results from the PANORAMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(9):946-955.

- Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, et al. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: The 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2013-2022.

- Hykin P, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, et al. Clinical effectiveness of intravitreal therapy with ranibizumab vs aflibercept vs bevacizumab for macular edema secondary to central Rretinal vein occlusion: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(11):1256-1264.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203.

- Khurana RN, Chang LK, Bansal AS, Palmer JD, Wu C, Wieland MR. Treat and extend regimen with aflibercept for chronic central retinal vein occlusions: 2 year results of the NEWTON study. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2019;5:10.

- Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al. Effect of bevacizumab vs aflibercept on visual acuity among patients with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: The SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2072-2087.

- Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Josic K, et al. Effect of intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor vs sham treatment for prevention of vision-threatening complications of diabetic retinopathy: The protocol W randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(7):701-712.

- Liu JC, Alsaloum P, Iyer A, Kaiser P, Singh R. Consequences of treatment lapse in retinal vein occlusion patients receiving anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(8):3188.