An important part of a discussion about geographic atrophy (GA) is how to define the term itself. Over time, understanding has grown about atrophy in the macula, and nomenclature has changed. Retinal Physician talks here with Glenn Jaffe, MD, about the efforts to clarify the definition of geographic atrophy and its subtypes.

RETINAL PHYSICIAN: HOW HAS THE TERM “GEOGRAPHIC ATROPHY” EVOLVED?

GLENN JAFFE, MD: Geographic atrophy was a term that was used based on color fundus photography to describe the appearance of retinal atrophic lesions in eyes with macular degeneration. It was defined by well-circumscribed round or oval areas of depigmentation at least 175 μm in diameter through which choroidal vessels are visualized. Over time, retina specialists have used newer modalities other than color fundus photography to assess GA. These include near-infrared reflectance, autofluorescence, and most notably optical coherence tomography.

The Consensus on Atrophy Meeting (CAM) group was convened to describe the preferred imaging modalities used to identify and follow eyes with atrophy and to define the terms used for atrophy, whether secondary to macular degeneration or other conditions, to identify risk factors for atrophy, and to determine how these risk factors might be used in clinical trials. I was part of this group, and we held a series of these consensus meetings and published several papers that addressed the consensus meeting objectives.

One of the consensus papers defined the various terms to determine the primary modality for assessing atrophy.1 The first term to define was the general term macular atrophy, which can apply to the atrophy that we see in different diseases, such as non-neovascular AMD, neovascular AMD, and hereditary retinal degenerations such as Stargardt disease.2 Then we worked to define specific terms based on OCT criteria. We retained the term “geographic atrophy” to refer to the atrophy that occurs exclusively in eyes with non-neovascular AMD. We did that primarily because that was the term that most retina specialists were accustomed to from the color fundus photograph days, and it was the term that most people were still using.

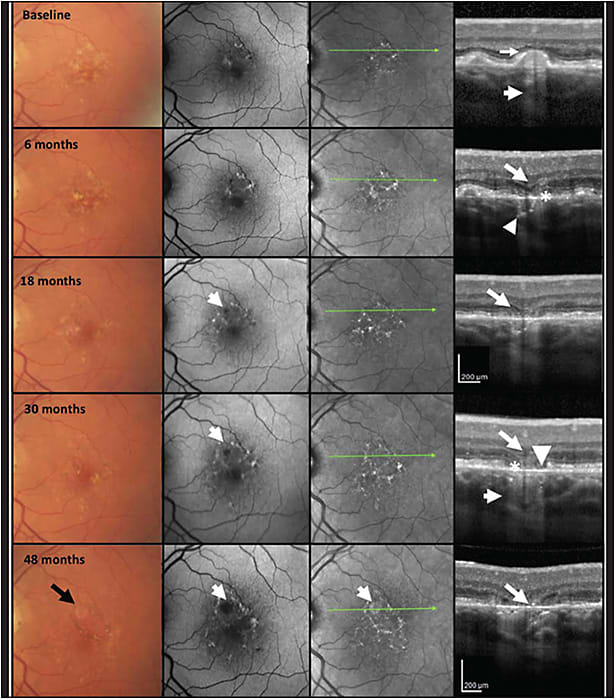

The CAM group defined macular atrophy by 3 main criteria on OCT: loss of the outer retina, loss of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choroidal hypertransmission. The latter 2 must be at least 250 μm in diameter (Figure 1).3 That number was chosen because we felt it was a size that could be reproducibly assessed by people who were reviewing the OCTs — namely, readers at a reading center.

As it has turned out, 250 μm works well as a cutoff for reproducibly identifying the lesions. The OCT correlate to the term geographic atrophy, which also is the OCT correlate for the more general term macular atrophy, is called complete RPE and outer retinal atrophy (cRORA). This term is defined by the above-mentioned 3 OCT criteria.

There is another term that is used when each of those 3 features are present, but do not meet the full criteria for GA or cRORA. This is called incomplete RPE and outer retinal atrophy (iRORA). These lesions may have some choroidal hypertransmission or disruption of the RPE, but they may not meet the full 250-μm threshold for cRORA. The lesions should have some degree of outer retinal atrophy as well.

RP: WHERE DOES NASCENT GA FIT INTO THIS DISCUSSION?

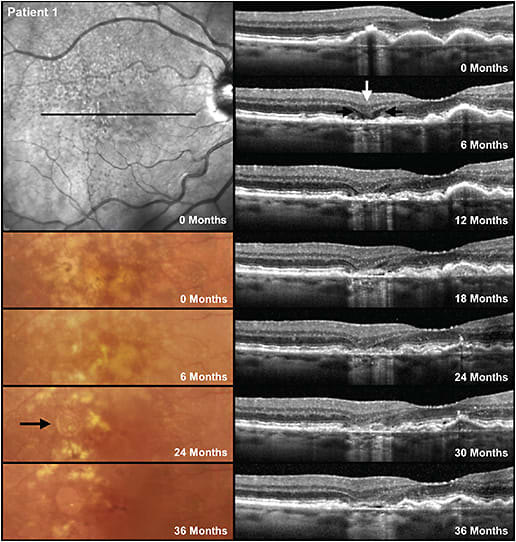

GJ: There has been confusion about distinguishing iRORA from nascent GA (nGA). This term was defined by Dr. Robyn Guymer’s group at the Centre for Eye Research Australia to describe signs that, when present, indicate a very high risk of progression to GA (Figure 2).4 The signs needed for nGA are the subsidence of the outer plexiform layer and inner nuclear layer, or a hyperreflective wedge-shaped lesion in Henle’s nerve fiber layer. There was no requirement for the presence of hypertransmission or RPE changes, although they are often present. Dr. Guymer’s research finds nGA to be more robust as a risk factor for progression than signs of iRORA.

Most cases of nGA will satisfy the definition of iRORA and sometimes cRORA. However, if for example there is no hypertransmission due to debris on Bruch’s membrane that is blocking the signal, then nGA may be present but not iRORA or cRORA. There are cases of iRORA in which the photoreceptor signs are simply a loss of the ellipsoid zone or external limiting membrane or thinning of the outer nuclear layer but no subsidence or wedge, and as such those patients do not have nGA. The subsidence of the outer plexiform layer and inner nuclear layer seem to be a sign that the loss of the photoreceptors is more advanced. Given that it has been difficult for researchers and clinicians to agree on the status of the RPE that is required to determine the presence of iRORA and cRORA, and that it is easier to reproducibly identify nGA, nGA appears a more robust sign when looking for early signs of atrophy on OCT.

So, nascent GA is specifically defined by the subsidence and the hyporeflective wedges, whereas cRORA is defined by those 3 OCT criteria described above with outer retinal loss, RPE loss, and choroidal hypertransmission at least 250 μm in diameter. One more important note is that RPE tear was excluded from the definition of cRORA. Although an RPE tear is associated with choroidal hypertransmission at the site of denuded RPE (or depigmented RPE that has slid over to cover Bruch’s membrane in the area of lost RPE), the overlying outer retinal layers are often mostly intact.

RP: WHAT ELSE SHOULD RETINA SPECIALISTS KEEP IN MIND ABOUT THESE DEFINITIONS?

GJ: Macular atrophy really is a general term. I was part of the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT), and in this study, which was a study of neovascular AMD comparing ranibizumab to bevacizumab, we looked at what we called geographic atrophy. If we were using current terminology, we wouldn’t have used the term geographic atrophy because that term is now specifically reserved for non-neovascular AMD. If I were writing the CATT papers today, I would use the term macular atrophy, because that’s the more general term and doesn’t specifically refer to non-neovascular AMD. However, we had not convened the consensus meetings at that point.

RP: WOULD IT BE BENEFICIAL IN THE FUTURE TO REVISIT THE TERMS?

GJ: It might help to have more clarity around iRORA and nascent GA. Most of the time patients who have nascent GA have iRORA, but they don’t always overlap perfectly. In fact, I would say nascent GA, which is really the earliest phases of geographic atrophy, is a stronger risk factor to progression to cRORA than is iRORA.

RP: IS THERE CONFUSION BETWEEN FOVEAL AND SUBFOVEAL ATROPHY, AND HOW DOES THAT AFFECT POTENTIAL THERAPIES?

GJ: Macula and fovea mean different things to histologists or anatomists than it does to clinicians. In particular, in clinical trials, there’s been ambiguity about the terms such that it has not always been clear what is meant when results of a trial are described regarding the location of the GA with respect to the foveal center. Some light is now being shed on those terms. The definition of fovea differs depending on what paper you read, but generally, the fovea is an oval region that is approximately 250 μm in radius.

Several clinical trials have used the terms foveal or extrafoveal for inclusion and exclusion criteria and when describing the results. These terms can be ambiguous when used in this manner. In Apellis’s DERBY and OAKS trials of pegcetacoplan for geographic atrophy, the term foveal was used to refer to foveal centerpoint involvement, not just involvement within that central zone.

Similarly, in Iveric Bio’s GATHER trials of avacincaptad pegol, foveal was used to idesribe eyes that had foveal center point involvement. This term had also earlier been called foveal involvement, which led to some confusion. People who had foveal center point involvement were excluded, so the lesion could come right up to the foveal center point, but if it was more than 0 μm away, then those people could be included in the trial. Somehow people started calling those extrafoveal lesions, even if they came right up to the foveal center, but they were within the foveal zone. To me, extrafoveal really means outside the fovea.

A better description of the criteria for trials and presentations might be non-foveal-center involving instead of extrafoveal. It’s more awkward, but it’s more descriptive. The equivalent ICD-10 diagnoses associated with these GA and pre-GA lesions are: “nonexudative AMD, intermediate dry stage” for high-risk drusen, iRORA, and nascent GA, “nonexudative AMD, advanced atrophic without subfoveal involvement” and “nonexudative AMD, advanced atrophic with subfoveal involvement.”

RP: WHAT MORE DO RETINA SPECIALISTS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THESE DEFINITIONS AS THEY RELATE TO CLINICAL TRIALS?

GJ: Non-neovascular AMD is a hot topic in clinical trials. Many drug companies have shifted their focus more toward non-neovascular AMD and away from neovascular AMD, because the bar is rising higher and higher to get drugs approved for neovascular AMD. However, it is challenging to target earlier phases of non-neovascular AMD with a clinical trial, because the FDA wants the endpoints to show meaningful results to the patient in visual acuity or vision-related function. It’s difficult to design a clinical trial with a reasonable number of patients over a reasonable timeframe when you start from the early phases that don’t progress quickly enough to detect a functional endpoint.

A huge opportunity for the future is to figure out how to design trials for non-neovascular AMD that have approvable endpoints, that have enough patients to demonstrate an effect but not so many patients to be cost prohibitive, and that can be recruited and completed within a reasonable timeframe. The biggest challenge with designing some of these earlier AMD trials is that the FDA has required a 3-line improvement in visual acuity, even in intermediate AMD trials. That’s been a challenge because it’s not often that patients develop that 3-line change. That was the issue for Stealth Biotherapeutics’ RECLAIM-2 trial of elamipretide that didn’t meet its endpoint, although it did have some signals to suggest that the drug had a beneficial effect.5 Allegro’s LUMINATE trial of risuteganib showed a higher proportion of 3-line gainers, a finding that inspires optimism for next-phase trials.6

The question that remains is whether there’s a way to come up with alternative endpoints or ways to design the trials that can satisfy the FDA’s requirement, or whether the FDA will modify the endpoints. The FDA usually will consider alternative endpoints if you can show that it’s a validated endpoint that is clinically meaningful. If we can come up with those and show that they’re clinically meaningful, we may be able to get away from needing to show 3-line improvement in visual acuity. An example might be a composite endpoint that includes several visual function tests, such as low-luminance visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and microperimetry. Including more than just a single visual function endpoint could also improve trial design and results. This approach is similar to a composite endpoint that has been used for uveitis, which includes several different uveitis features, not just one.7

This is a very exciting time in retina, and I believe that it will not be long before we have approved treatments for GA. It will be especially important going forward, as we design trials that target earlier AMD disease stages, that we communicate definitions of AMD biomarkers, trial endpoints, methodology, and results with standardized terminology to minimize confusion and to move the field forward. RP

Editor’s note: This article is part of a special edition of Retinal Physician that was supported by Apellis Pharmaceuticals. Authors and editors maintained editorial control for all articles in this special edition.

REFERENCES

- Sadda SR, Guymer R, Holz FG, et al. Consensus definition for atrophy associated with age-related macular degeneration on OCT: classification of atrophy report 3 [published correction appears in Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan;126(1):177]. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(4):537-548. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.028

- Jaffe GJ, Chakravarthy U, Freund KB, et al. Imaging features associated with progression to geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 5. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(9):855-867. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2020.12.009

- Guymer RH, Rosenfeld PJ, Curcio CA, et al. Incomplete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 4. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(3):394-409. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.035

- Wu Z, Luu CD, Hodgson LAB, et al. Prospective longitudinal evaluation of nascent geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(6):568-575. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2019.12.011

- Stealth Biotherapeutics announces data from RECLAIM-2 phase 2 trial of elamipretide in geographic atrophy. News release. May 2, 2022. Accessed November 11, 2022. https://investor.stealthbt.com/websites/stealthbio/English/5200/us-press-release.html?airportNewsID=e06fe2cb-dcaa-4303-8630-94ee8ef714db

- Boyer DS, Gonzalez VH, Kunimoto DY, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravitreal risuteganib for non-exudative AMD: a multicenter, phase 2a, randomized, clinical trial. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2021;52(6):327-335. doi:10.3928/23258160-20210528-05

- Jaffe GJ, Dick AD, Brézin AP, et al. Adalimumab in patients with active noninfectious uveitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1509852