According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, in 2019 the average spending on prescribed medications per capita in the United States was $1,126 (an increase of 69% compared to 2004), much more than the $552 per capita average in comparable countries.1 Based on wholesale acquisition costs, single doses of the most commonly used anti-VEGF agents vary considerably: aflibercept 6 mg (Eylea; Regeneron) costs $1,830, ranibizumab 0.3 mg (Lucentis; Genentech) costs $1,170, and repackaged 1.25 mg bevacizumab at compounding pharmacies costs approximately $70.2 Ranibizumab and aflibercept costs account for 12% of the Medicare Part B budget annually: $9,719 per beneficiary for ranibizumab and $9,934 per beneficiary for aflibercept.3

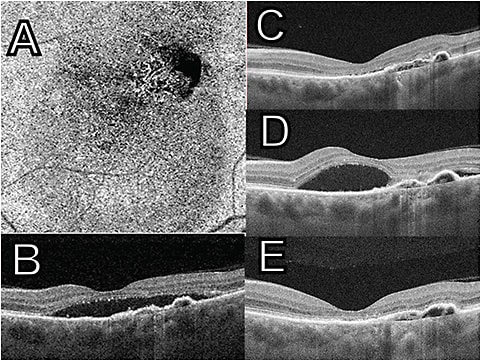

To attenuate the cost part of their ledger, many insurance companies have instituted a “step therapy” approach. The central tenet of the step therapy insurance paradigm is to try less expensive therapeutic options first, only “stepping up” to drugs that cost more if the initial treatment fails to meet the desired goal. Therefore, for some, step therapy is referred to as “fail first” therapy (Figure 1).

A recent study attempted to define the suitability of a step therapy approach with one of the most common and serious clinical scenarios in retina: the management of diabetic macular edema (DME). The report, from the DRCR Network (Protocol AC),4 compared outcomes for patients with center-involving DME at 2 years when starting off with intravitreal aflibercept vs starting with intravitreal bevacizumab.

Previously, in the Protocol T study,5 a comparative “non-step” trial of these drugs showed similar outcomes in eyes with a baseline visual acuity of 20/40 or better. However, in this study, in eyes with a baseline visual acuity of 20/50 or worse, aflibercept treatment resulted in better vision than bevacizumab therapy at 2 years (mean improvement, 18.1 letters with aflibercept vs 13.3 letters with bevacizumab) and better vision through 1 year than ranibizumab therapy. Still, 68% in the bevacizumab group who initially had 20/50 vision or worse obtained visual acuity of 20/40 or better at 2 years.

The Protocol AC step therapy study included 270 participants with initial visual acuity from 20/30 to 20/50, some of whom received treatments in both eyes. Half of the patients were assigned to aflibercept from the start, and half were assigned to start with bevacizumab. For participants who needed treatment in both eyes, each eye started treatment with a different drug.

Participants initially received injections of either aflibercept or bevacizumab every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. If eyes assigned bevacizumab failed to reach the preset benchmarks of vision and macular edema starting at 12 weeks, the eye was switched to aflibercept. Follow-up visits took place every 4 weeks during the first year, followed by every 4 weeks to 16 weeks during the second year, depending on the examination findings.

At 24 weeks and 52 weeks, switching criteria were met in 39% and 60%, respectively, in the bevacizumab-first group. At the end of 2 years, 70% of the bevacizumab group needed to be switched to aflibercept according to the preset criteria. After this time, eyes in both groups had similar visual acuity outcomes, improving on average approximately 3 lines on an eye chart, compared to the start of the trial. Eyes in the aflibercept monotherapy group required fewer injections: a mean of 14.6±4.1 injections vs those in the bevacizumab-first group, who required 16.1±4.1 injections.

Does the result of this carefully monitored study warrant consideration of step therapy in this scenario? At the end of the study, because 70% of the bevacizumab-first patients were receiving aflibercept, was the study really comparing different groups? Will physicians in the “real world” be able to adhere to strict switching criteria if treatment is initiated with bevacizumab? Will patients with diabetes in the “real world” demonstrate follow-up visit compliance to give us confidence that physicians will be able to monitor them efficiently enough to determine when switching is necessary? This month, we are fortunate to have expert commentary from Reginald Sanders, MD, regarding this important issue.

Weighing Cost and Outcomes

Reginald Sanders, MD

Since 2019, CMS has allowed Medicare Advantage plans to use less expensive medications for Part B drugs (step therapy). In the retina arena, this mostly meant the use of the less expensive bevacizumab for a period time to treat DME before the use of the more expensive medications, such as ranibizumab and aflibercept. Over time, this cost-cutting policy has been adopted by a growing number of medical insurers. This policy is at odds with physicians who value using their experience, clinical data, and judgement to treat their patients’ DME as they best see fit, as well as with patients who desire to receive the best care and treatment.

The American Society of Retinal Specialists and the American Academy of Ophthalmology have been assiduously lobbying CMS and Congress to rescind the step therapy policy. Step therapy, also known as fail-first therapy, has raised concerns about best care for DME. Dr. Colucciello has expertly and effectively illustrated this above with discussions of 2 pivotal DCRC studies, Protocols T and AC.

Although Protocol T was not step therapy, it clearly showed the superiority of aflibercept over bevacizumab in the treatment of patients with DME with vision worse than 20/50. Protocol AC showed that over time, patients with DME treated first with bevacizumab had to be switched over to aflibercept by an increasing percentage to achieve the same results as the monotherapy aflibercept group. In addition, more injections were required in the step-therapy group to reach the same results. Thus, it is difficult to make the case clinically, morally, or financially that step therapy treatment for DME is warranted or beneficial for our patients. RP

REFERENCES

- Kurani N, Cotliar D, Cox C. How do prescription drug costs in the United States compare to other countries? Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-do-prescription-drug-costs-in-the-united-states-compare-to-other-countries/#Per%20capita%20prescribed%20medicine%20spending,%20U.S.%20dollars,%202004-2019

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2022 ASP drug pricing files. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/2022-asp-drug-pricing-files

- Patel S. Medicare spending on anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medications. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(8):785-791. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2017.12.006

- Jhaveri CD, Glassman AR, Ferris FL 3rd, et al. Aflibercept monotherapy or bevacizumab first for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):692-703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204225

- Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-1359. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.022