Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of blindness in working-age adults in the United States.1 The latest guidelines recommend at least yearly screening for all people with diabetes, beginning at diagnosis for type 2 diabetes and within 3 to 5 years of diagnosis for type 1 diabetes, with more frequent visits required for advanced disease.2 Given the current prevalence estimates of diabetes, 37.3 million people in the United States require annual DR screening, with a subset of 10.6 to 15 million people expected to require more frequent screening. Adequate screening requires examination of both visual acuity and the retina, with the gold standard being a dilated fundus exam (Figure 1).2

Without a centralized screening system, patients obtain screening directly from their individual eye care providers or by referral from their primary care providers. Screening can be performed by the approximately 19,000 ophthalmologists and the 38,730 optometrists in practice in the United States.3,4 Rough calculations estimate a daily load of 3 to 15 DR screenings per eye care provider, which may seem feasible given that the average ophthalmologist in the United States sees 30 to 50 patients per day. However, these numbers do not include encounters for the management of DR, or the ophthalmic needs of the rest of the population.

Screening Rates

Despite the alarming number of screenings theoretically needed, the clinical burden of DR has not yet overwhelmed the American eye health system in part because patient adherence to screening guidelines is relatively low. In 2020, only 58.3% of adults diagnosed with diabetes had an eye exam within the last year, down from 64.8% in 2019.5 Low screening rates are of particular concern as DR is a progressive disease, increasing in prevalence and severity with patient age and duration of diabetes.1

Disparities

Increasing the proportion of people with diabetes who obtain an annual eye exam has been identified as a national priority; improving the screening rate to 70.3% is a Healthy People 2030 objective.5 In pursuit of this goal, it is important to investigate the barriers and reasons behind low adherence to screening guidelines. Several factors have been associated with lower screening rates, including lower socioeconomic status, Black race or Hispanic ethnicity, living in rural or disadvantaged communities, and lack of health insurance.6 Lack of health insurance is one of the most salient barriers to DR screening, with 76% of insured Americans obtaining annual screening compared to only 36% of those who are uninsured. Screening rates remain low at 54.1% even for patients with Medicare, under which DR screening is covered, with even lower rates among Black and Hispanic individuals in this group.7

Self-reported barriers to care in one survey included having too many medical appointments, inability to afford screening, and no perceived vision problems.8 Another survey was conducted on a group of patients at high risk of nonadherence to screening. These patients were primarily Hispanic or Black and of lower socioeconomic status at a safety-net clinic in Los Angeles, California. Overall, 55% of respondents had received a screening exam in the last year, despite 93% acknowledging that they were aware that diabetes can cause vision loss.9 The 2 most commonly reported barriers to screening were financial problems (26%) and depression (22%). Interestingly, these responses significantly differed from barriers endorsed by providers at the same clinic, illustrating that there is a disconnect in perception between patients and providers.

Advances in Screening

In other countries, including the United Kingdom, task-sharing has been used to shift some of the burden of DR screening away from eye care professionals. In the United States, primary care providers may be a largely untapped resource in DR screening. Most adults with diabetes, including those at high risk of missing their annual screening, have regular appointments with a primary care physician.10 Primary care providers also tend to be more uniformly distributed around the country and in rural areas, in contrast with ophthalmologists who cluster in urban centers.

However, fundoscopic screening in the primary care setting has not been shown to be effective; a study in 2022 revealed that primary care providers only performed funduscopic examinations on 12% of patients, with a sensitivity for detecting disease of 0%.11 Nurse practitioners make up a significant portion of the primary care workforce, especially in underserved areas, and were even less likely to perform fundoscopy compared to their physician counterparts. These findings indicate that the fundoscopic exam is not optimal for DR screening in the primary care setting.

Teleretina

One proposed method of improving the DR screening rate is the use of teleretina, with or without the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI). Teleretina is an alternative to direct examination by an eye care provider whereby staff take retinal images and transmit them elsewhere for interpretation by a trained grader. This model has been proposed to be cost-effective and rapid, taking only 15 to 20 minutes for retinal imaging and with good sensitivity and specificity compared to the gold-standard dilated fundus examination.

Nonmydriatic fundus photography has been used in the primary care setting and shown to improve adherence to follow-up and reduce the clinical load for eye care providers.12 These teleretina programs have been demonstrated to be cost effective, particularly in rural and low-income settings.13 Teleretina has also been implemented in the emergency department and revealed a high prevalence of previously undiagnosed DR, suggesting that this setting may be another point of contact for screening high-risk individuals.8

In the last 2 years, teleretina has expanded to other outpatient and commercial sites. As of 2022, both CVS Health and Quest Diagnostics offer DR exams (Figure 2). Until August 2023 when the service was discontinued, CVS Health offered teleretina exams at all of the more than 1,200 MinuteClinic locations using the Welch Allyn RetinaVue 700 Imager and an off-site ophthalmologist. Patients could walk in or make appointments online.14 Quest Diagnostics has collaborated with Intelligent Retinal Imaging Systems (IRIS) to expand DR screening at their patient service centers.15 These programs may make screening more accessible to individuals, reducing the barrier of obtaining appointments or referrals from primary care providers, and continue to shift the burden of screening off of more specialized eye care professionals.

Diabetic retinopathy screening centers using a teleretina model have been implemented in the United Kingdom as a method of streamlining the screening process and task-sharing to newly trained staff rather than medical professionals. Screening rates for newly registered patients in this screening pathway are 80% within the first year and up to 88% within 3 years.16

One of the factors that makes this model more feasible in the United Kingdom than the United States is the publicly funded National Health Service. The fractured nature of the payor system in the United States makes establishing and funding screening clinics more complicated, but a screening clinic to serve the publicly funded Medicare, Medicaid, and Veterans Affairs (VA) populations may be worth further investigation. It has already been shown that teleretinal screening is cost effective in the VA setting, while also increasing screening participation and expanding care to more traditionally difficult to reach demographics.17

Similarly, because lack of insurance is such a strong predictor of reduced adherence to screening guidelines, a safety net screening center may be of use in reaching this population. A statewide teleretina program based in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in Kentucky increased the mean screening rate from 29.9% to 47.7% in the first year, sustaining this gain over 4 years, and found that patients preferred the teleretina system to specialist exams.18 In January of this year, a $2 million grant was awarded to launch the interdisciplinary Collaborative UC Teleophthalmology Initiative (CUTI), which will expand and integrate teleretina screening into primary care clinics as well as FQHCs in California.19 These programs are exciting steps toward equitable access to diabetic eye care for underserved populations in the United States.

Artificial Intelligence

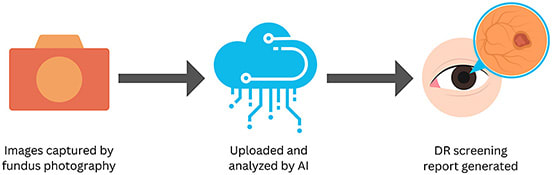

Developments in AI have been promising for the future of DR screening, at least as an adjunct tool (Table 1; Figure 3). Color photographs are taken with a fundus camera and uploaded to the cloud, where the AI algorithm analyzes the images for signs of DR and reports whether DR is detected.20 These AI platforms are designed to allow for autonomous screening, streamlining the process and eliminating the need for a specialist grader. This is of particular significance for increasing access to screening in areas with shortages of trained personnel. Although there are several AI algorithms focused on DR in development around the world, there are currently 3 cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration: LumineticsCore (formerly known as IDx-DR) by Digital Diagnostics, EyeArt by Eyenuk, and Aeye Diagnostic Screening by Aeye Health.21-23 Additionally, Retina-AI Galaxy by Retina-AI Health is reportedly seeking FDA clearance pending the results of its phase 3 trial, which concluded on March 31, 2023 (NCT05368623).24 The introduction of CPT code 92229 in 2021 allows for screening with AI to be reimbursable, reflecting the burgeoning use of this modality in the United States.25

| Algorithm | Company | FDA Cleared | Compatibility | Detection | Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

| LumineticsCore (formerly IDx-DR) | Digital Diagnostics | 2018 | Topcon NW400 | mtmDR | 87.4%(81.9%-92.9%) | 89.5% (86.9%-93.1%) |

| EyeArt | Eyenuk | 2020 | Canon CR-2 AF, Canon CR-2 Plus AF, Topcon NW400 | mtmDR | 95.5% (92.4%-98.5%) |

85% (82.6%-87.5%0 |

| vtDR | 95.1% (90.1%-100%) |

89% (87%-91.1%) |

||||

| Aeye-DS | Aeye Health | 2022 | Topcon NW400 | mtmDR | 93% (83.3%-97.2%) |

91.4% (88.2%-93.7%) |

| mtmDR, more than mild diabetic retinopathy; vtDR, vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy. | ||||||

LumineticsCore

Initially cleared by the FDA in 2018 with the name IDx-DR, this AI platform by Digital Diagnostics was rebranded as LumineticsCore in March 2023 (Figure 4). LumineticsCore is indicated for detection of the presence of more than mild DR.21 In April of 2023, Digital Diagnostics announced its partnership with Labcorp to bring LumineticsCore AI screening to 9 sites across Alabama, where it can be ordered by physicians similarly to other Labcorp tests. This is the first offering of autonomous AI in a patient service center environment, significantly expanding access to this type of screening.

EyeArt

The EyeArt AI Eye Screening System by Eyenuk is the only AI algorithm cleared by the FDA for detection of both more than mild DR and vision-threatening DR (Figure 5).22,26 It was also cleared in June 2023 for use with Topcon NW400 cameras in addition to the Canon CR-2 AF and CR-2 Plus AF models, making it the only algorithm cleared for use with multiple camera models.

Aeye-DS

The newest AI algorithm to the scene, Aeye-DS was cleared by the FDA in 2022 for screening of more than mild DR (Figure 6).23 A unique feature of this algorithm by Aeye Health is that it requires a single image per eye, in contrast to LumineticsCore and EyeArt, which both use 2 images per eye.

Conclusion

Screening for DR in the United States is suboptimal and rife with significant disparities. However, the landscape of DR screening is rapidly changing, with exciting innovations on the horizon in both teleretina and AI. As these fields continue to grow, there is potential for improvement in equitable access to and the overall rate of DR screening nationwide.

References

- National Eye Institute. People with diabetes can prevent vision loss. National Institutes of Health. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.nei.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2019-06/diabetes-prevent-vision-loss.pdf

- Wong TY, Sun J, Kawasaki R, et al. Guidelines on diabetic eye care: the international council of ophthalmology recommendations for screening, follow-up, referral, and treatment based on resource settings. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1608-1622. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.007

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Eye health statistics. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.aao.org/newsroom/eye-health-statistics#_edn25

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages: optometrists. March 2022. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291041.htm

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Increase the proportion of adults with diabetes who have a yearly eye exam. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/diabetes/increase-proportion-adults-diabetes-who-have-yearly-eye-exam-d-04

- Eppley SE, Mansberger SL, Ramanathan S, Lowry EA. Characteristics associated with adherence to annual dilated eye examinations among US patients with diagnosed diabetes. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(11):1492-1499. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.05.033

- Lundeen EA, Wittenborn J, Benoit SR, Saaddine J. Disparities in receipt of eye exams among medicare part B fee-for-service beneficiaries with diabetes — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019. 2019;68:1020-1023. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a3external

- Williams AM, Weed JM, Commiskey PW, Kalra G, Waxman EL. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and self-reported barriers to eye care among patients with diabetes in the emergency department: the diabetic retinopathy screening in the emergency department (DRS-ED) study. BMC Ophthalmology. 2022;22(1):237. doi:10.1186/s12886-022-02459-y

- Lu Y, Serpas L, Genter P, Anderson B, Campa D, Ipp E. Divergent perceptions of barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening among patients and care providers, Los Angeles, California, 2014-2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E140. doi:10.5888/pcd13.160193

- Gibson DM. Estimates of the percentage of US adults with diabetes who could be screened for diabetic retinopathy in primary care settings. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(4):440-444. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.6909

- Song A, Lusk JB, Roh K-M, et al. Practice patterns of fundoscopic examination for diabetic retinopathy screening in primary care. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(6):e2218753-e2218753. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18753

- Liu J, Gibson E, Ramchal S, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening with automated retinal image analysis in a primary care setting improves adherence to ophthalmic care. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(1):71-77. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2020.06.016

- Avidor D, Loewenstein A, Waisbourd M, Nutman A. Cost-effectiveness of diabetic retinopathy screening programs using telemedicine: a systematic review. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2020;18:16. doi:10.1186/s12962-020-00211-1

- Gustaitis J. CVS now offering retinopathy exams. Diabetes Self-Management. March 4, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.diabetesselfmanagement.com/news-research/2022/03/04/cvs-now-offering-retinopathy-exams/

- Quest Diagnostics adds diabetic retinopathy screening through its patient service centers in collaboration with IRIS. April 4, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://newsroom.questdiagnostics.com/2022-04-04-Quest-Diagnostics-Adds-Diabetic-Retinopathy-Screening-Through-its-Patient-Service-Centers-in-Collaboration-with-IRIS

- Lawrenson JG, Bourmpaki E, Bunce C, Stratton IM, Gardner P, Anderson J. Trends in diabetic retinopathy screening attendance and associations with vision impairment attributable to diabetes in a large nationwide cohort. Diabet Med. 2021;38(4):e14425. doi:10.1111/dme.14425

- Kirkizlar E, Serban N, Sisson JA, Swann JL, Barnes CS, Williams MD. Evaluation of telemedicine for screening of diabetic retinopathy in the Veterans Health Administration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2604-2610. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.029

- Bastos de Carvalho A, Ware SL, Lei F, Bush HM, Sprang R, Higgins EB. Implementation and sustainment of a statewide telemedicine diabetic retinopathy screening network for federally designated safety-net clinics. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241767. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241767

- UC Davis Health. UC Davis Health leads $2M program to improve eye care for people with diabetes. January 9, 2023. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/uc-davis-health-leads-2m-program-to-improve-eye-care-for-people-with-diabetes/2023/01

- Grzybowski A, Singhanetr P, Nanegrungsunk O, Ruamviboonsuk P. Artificial intelligence for diabetic retinopathy screening using color retinal photographs: from development to deployment. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12(3):1419-1437. doi:10.1007/s40123-023-00691-3

- Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:39. doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. EyeArt 510(k) Clearance Approval Letter. 2020. Regulatory Requirements for Medical Devices. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf20/K200667.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. AEYE 510(k) clearance approval letter. 2022. Regulatory Requirements for Medical Devices. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf22/K221183.pdf

- RETINA-AI Health, Inc. closes $2.6M bridge round; totaling $8.1M raised to build Galaxy multi-camera-compatible diabetic retinopathy AI system. Starts clinical trial. December 12, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/retina-ai-health-inc-closes-2-6m-bridge-round-totaling-8-1m-raised-to-build-galaxy-multi-camera-compatible-diabetic-retinopathy-ai-system-starts-clinical-trial-301699978.html

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Billing and coding: remote imaging of the retina to screen for retinal diseases. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/article.aspx?articleid=58914#:~:text=CPT%C2%AE%2092229%20allows%20coverage,and%20report%2C%20unilateral%20or%20bilateral

- Ipp E, Liljenquist D, Bode B, et al. Pivotal evaluation of an artificial intelligence system for autonomous detection of referrable and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2134254. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34254

Editor's note: This article was updated October 5, 2023, to reflect that in August 2023, MinuteClinic had discontinued its retinal screening program.