Retina specialists often rely on pattern recognition to initially triage patients. Masquerade syndromes challenge the ability to differentiate pathologies, because symptoms can mimic a uveitic condition, but may herald a concerning systemic diagnosis, such as cancer or a paraneoplastic syndrome.1 These conditions can elude even the most well-versed clinicians, but attention to the clinical course and lack of response to traditional interventions should raise the possibility of a masquerade syndrome. Oncologic conditions include diffuse anterior retinoblastoma, lymphoma, leukemia, and choroidal lesions, such as amelanotic tumors including uveal metastasis or necrotic choroidal melanoma that occasionally presents with sharp pain. Paraneoplastic masquerades include acute exudative paraneoplastic polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy (AEPPVM) and bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP).2 This article will describe important neoplastic and paraneoplastic conditions that can masquerade as uveitis, as well as their differentiating features.

NEOPLASTIC

Diffuse Anterior Retinoblastoma

Diffuse anterior retinoblastoma is a subtype of retinoblastoma in which tumor deposition occurs primarily in the anterior segment with minimal or no retinal involvement.3 Shields et al published 3 cases with the average age at presentation being older than typical retinoblastoma at 5.7 years (median, 7; range, 3-7 years). In these cases, the entire tumor is localized to the anterior segment, often with pseudohypopyon, but unlike endophthalmitis or uveitis, the eye is usually white and quiet without much pain.3

In addition, children with posterior-segment retinoblastoma can present with unilateral pseudohypopyon that mimics anterior uveitis, but again, the eye is usually comfortable, not injected and without posterior synechia.3 In such cases, a solid retinoblastoma might be found posteriorly in the eye on clinical evaluation and with ultrasonography. Cytologic confirmation from an anterior-chamber tap through a clear corneal approach can be done with caution not to seed the tumor outside the eye, but the safest alternative is to refer to an ocular oncologist for final diagnosis and therapy.3 In the past, pseudohypopyon was an indication for enucleation, but now eyes with retinoblastoma pseudohypopyon can often be saved with methods of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Lymphoma

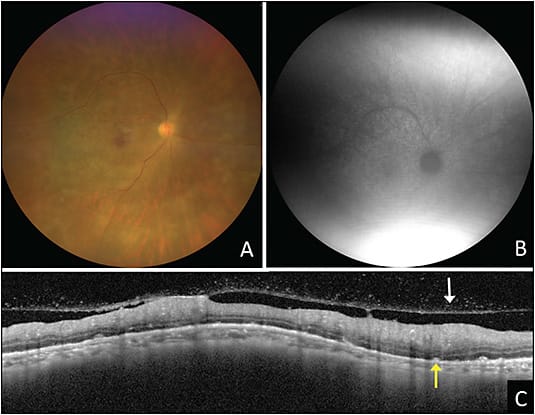

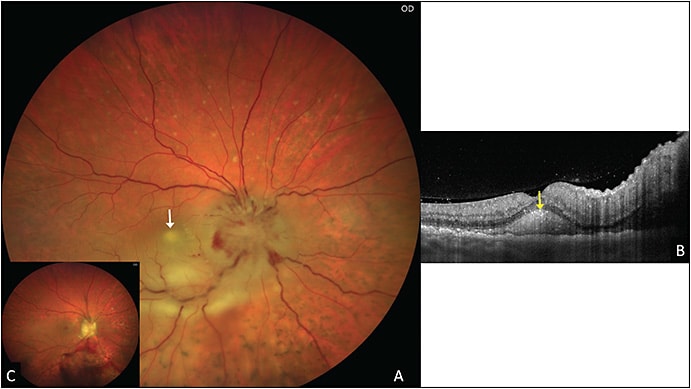

Intraocular lymphoma is subdivided into 3 groups: primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL), choroidal lymphoma, and, rarely, iris lymphoma.2 Classically, PVRL presents with sub–retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) infiltrates and vitreous cells (often with a clumped appearance) (Figure 1). Other findings include keratic precipitates, retinal and/or subretinal infiltrates, cloudy vitelliform submaculopathy (Figure 2), and optic nerve invasion.2,4 Less commonly, PVRL can present with hyphema, pseudohypopyon, exudative retinal detachment, or pseudovasculitis.2 Most cases of PVRL are linked to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with less than 5% representing T-cell lymphoma. Diagnosis can be made with vitrectomy or fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) with cytologic assessment and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. It is not uncommon to require more than 1 vitreous biopsy because sample analysis can be limited by cellular yield and the fragility of lymphoma cells.

Recently, PCR testing for MYD88 from the vitreous and aqueous has emerged as a reliable marker for establishing diagnosis.2 Lymphoma can temporarily respond to corticosteroids initially and can even spontaneously resolve, but this malignancy classically recurs if no treatment is given. In the case of considering a biopsy, oral corticosteroids should be stopped at least 2 to 4 weeks prior to the biopsy to increase the cellular yield of the sample.2 When the diagnosis of PVRL is made, it is crucial to obtain MRI imaging of the brain and lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis to rule out central nervous system disease on a 6-month basis and properly stage the cancer, given its aggressive nature.

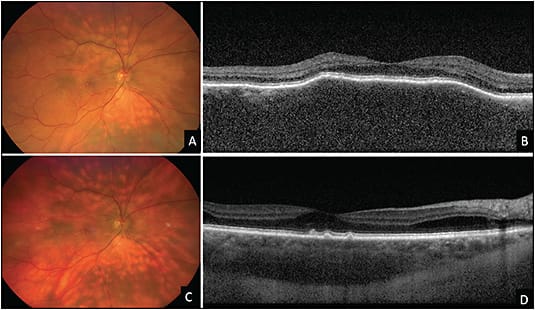

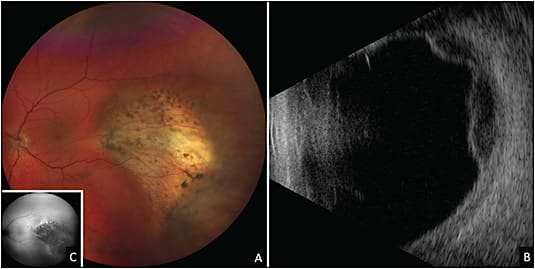

Choroidal lymphoma is a low-grade malignancy with most cases representing extranodal marginal zone lymphoma, otherwise known as mucosa-associated lymphoid tumor. This manifests with diffuse or patchy choroidal infiltration and rarely with nodular choroidal lesions. A classic “seasick” undulating choroidal surface on OCT is suggestive of this condition. On ultrasonography, choroidal lymphoma will show diffuse choroidal thickening within the eye, often with echolucent extrascleral tumor.5 Fine needle aspiration biopsy from the choroidal tumor can establish the diagnosis (Figure 3).5

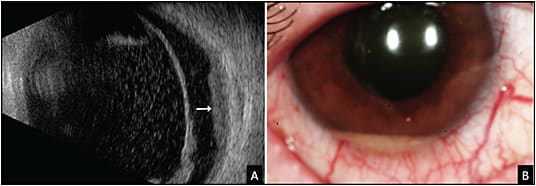

Iris lymphomas manifests with keratic precipitates, pseudohypopyon, hyphema, heterochromia, and diffuse iris thickening, often with congestion of conjunctival and/or episcleral vessels (Figure 4).6 Fine needle aspiration biopsy can help in establishing the diagnosis, and chemotherapy or radiotherapy are effective modes of treatment.

Leukemia

Leukemic retinopathy can masquerade as uveitis. Anterior manifestations include pseudohypopyon, occasionally with a hemorrhagic component.7 Posterior manifestations involve vitreous and/or optic nerve infiltration, serous retinal detachment, and perivascular sheathing.7 Peripheral blood smear examination, bone marrow biopsy, and sampling of the aqueous humor or vitreous tap can help to reach a definitive diagnosis.8

Amelanotic Choroidal Tumors

Amelanotic choroidal tumors, such as melanoma, nevus, osteoma, sclerochoroidal calcification, and hemangioma, can mimic granulomatous inflammatory conditions or posterior scleritis.8 Ultrasonography is instrumental in narrowing the differential diagnosis, with melanoma having low echodensity, nevus with high echodensity, osteoma and sclerochoroidal calcification showing calcium deposits with a shadow posterior to the lesion, and hemangioma with high echodensity of approximately 3 mm thickness.8 Angiography differs in these specific tumors, but is most helpful with circumscribed choroidal hemangioma that demonstrates a classic early hyperfluorescence on fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), which increases in intensity in the later phases, while indocyanine green angiography shows rapid filling of the mass within 1 minute and washout of the dye in the late recirculation phase.8

Metastasis

Uveal metastasis mostly involves the posterior segment, posterior to the globe equator (Figure 5), with rare cases presenting with primarily anterior infiltration or retinal metastases.9 Choroidal metastasis is seen most commonly from breast and lung cancers and less commonly from kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and other tumors.9 This presentation can appear similar to sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, nodular posterior scleritis, and inflammatory/infectious chorioretinal lesions.9 An echodense appearance on ultrasonography and “lumpy bumpy” choroidal contour with compression of choriocapillaris on optical coherence tomography are suggestive of the diagnosis.9 Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the lesion often confirms the diagnosis.9 Anterior-segment metastases are rare (less than 20%) and can present with pseudohypopyon.9

Although rare, retinal metastasis most commonly arises from cutaneous melanoma, breast, lung, and esophageal cancers.9 This malignancy can mimic a retinal infection like viral (cytomegalovirus or herpes virus), or bacterial retinitis, fungal abscess, and other infections. Careful systemic evaluation, and in certain cases, biopsy can confirm the diagnosis (Figure 6).

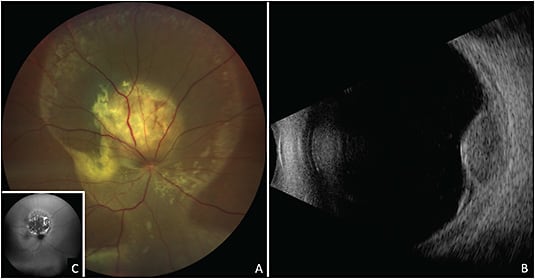

Necrotic Choroidal Melanoma

Rarely, choroidal melanoma can undergo necrosis and lead to a painful red eye with features of scleritis and uveal effusion creating a diagnostic dilemma (Figure 7).10 In such cases, ultrasonography will reveal a mass with low to moderate echolucency and characteristic intrinsic vascular pulsations. On magnetic resonance imaging, the mass will be discrete and show positive gadolinium enhancement on T1 images.10 If doubt remains, FNAB of the mass can be confirmatory.

PARANEOPLASTIC

Acute Exudative Paraneoplastic Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy

Macular vitelliform deposits are associated with both benign and cancerous conditions.4,11 Paraneoplastic conditions associated with AEPPVM include cutaneous melanoma and metastatic carcinomas, and can also be seen in conjunction with PVRL and often have multiple, discrete subretinal vitelliform lesions throughout the fundus.11 Systemic evaluation of cancer can help confirm the diagnosis.

Bilateral Diffuse Uveal Melanocytic Proliferation

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation is a paraneoplastic condition often presenting with multiple orange-red or pigmented subretinal lesions (giraffe-type patches on autofluorescence and angiography), diffuse choroidal thickening, and exudative retinal detachment.2 Other signs includes acquired hyperopia, rapidly developing cataract, raised intraocular pressure, and mucosal hyperpigmentation.12 This condition has been described with primary carcinomas of the lung, ovary, uterus, cervix, colon, gall bladder, kidney, and pancreas.2 Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation can be mistaken for uveal effusion syndrome, multifocal choroiditis, sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, posterior scleritis, and sympathetic ophthalmia.2

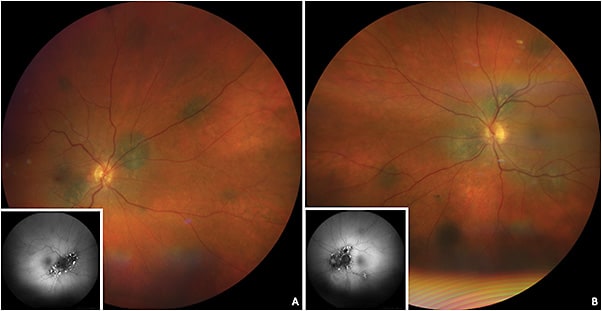

Characteristic features of BDUMP on imaging include hyperfluorescent patches on FFA due to window defects, both hyperautofluorescence and hypoautofluorescence due to RPE irritation and damage seen on fundus autofluorescence, and thickening of the choroid and RPE on OCT (Figure 8).2 A thorough history and systemic evaluation is helpful in determining the primary cause.

CONCLUSION

Various neoplastic disorders can mimic both infectious and noninfectious uveitis. Keeping these neoplastic and paraneoplastic conditions as the differential diagnosis is useful, particularly in patients who do not respond to traditional uveitis therapy. A careful history and ocular examination, as well as the employment of imaging and diagnostic biopsy, can elucidate the diagnosis. RP

REFERENCES

- Rothova A, Groen F, Ten Berge JCEM, Lubbers SM, Vingerling JR, Thiadens AAHJ. Causes and clinical manifestations of masquerade syndromes in intraocular inflammatory diseases. Retina. 2021;41(11):2318-2324. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003171

- Touhami S, Audo I, Terrada C, et al. Neoplasia and intraocular inflammation: From masquerade syndromes to immunotherapy-induced uveitis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;72:100761. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.05.002

- Shields CL, Lally SE, Manjandavida FP, Leahey AM, Shields JA. Diffuse anterior retinoblastoma with globe salvage and visual preservation in 3 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2):378-384. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.040

- Kalafatis NE, Agrawal KU, Ehya H, Shields CL. Cytology-proven primary vitreoretinal lymphoma in a patient with paraneoplastic cloudy vitelliform submaculopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(7):744-745. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.1554

- Mashayekhi A, Hasanreisoglu M, Shields CL, Shields JA. External beam radiation for choroidal lymphoma: efficacy and complications. Retina. 2016;36(10):2006-2012. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001026

- Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Iris involvement by lymphoma: a review of 13 cases. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(1):19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02811.x

- Kim TS, Duker JS, Hedges TR 3rd. Retinal angiopathy resembling unilateral frosted branch angiitis in a patient with relapsing acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(6):806-808. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70329-0

- Welch RJ, Newman JH, Honig SE, et al. Choroidal amelanotic tumours: clinical differentiation of benign from malignant lesions in 5586 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(2):194-201. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313680

- Shields CL, Kalafatis NE, Gad M, et al. Metastatic tumours to the eye. Review of metastasis to the iris, ciliary body, choroid, retina, optic disc, vitreous, and/or lens capsule [published online ahead of print, 2022 Mar 19]. Eye (Lond). 2022;10.1038/s41433-022-02015-4. doi:10.1038/s41433-022-02015-4

- Palamar M, Thangappan A, Shields CL, Ehya H, Shields JA. Necrotic choroidal melanoma with scleritis and choroidal effusion. Cornea. 2009;28(3):354-356. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181875463

- Lambert I, Fasolino G, Awada G, Kuijpers R, Ten Tusscher M, Neyns B. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy during pembrolizumab treatment for metastatic melanoma: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1):250. Published 2021 Jun 5. doi:10.1186/s12886-021-02011-4

- Prasuhn M, Rommel N, Kakkassery V, Grisanti S, Ranjbar M, Rommel F. Rare case of bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation with dermal and mucosal hyperpigmentations. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(11):2052. Published 2021 Nov 5. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11112052