Retinal whitening occurs secondary to a multitude of causes — ischemic, infectious, inflammatory, traumatic, neoplastic, therapeutic, and idiopathic. A patient’s history, demographics, and comorbid medical conditions help inform the diagnosis. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a key component of making a diagnosis and prognostication. This article reviews intralesional OCT findings of various etiologies of retinal whitening, using the proposed lexicon for retinal layers from the 2014 International Nomenclature for Optical Coherence Tomography Panel.1 This review will include several causes of retinal whitening, with an emphasis on clinically pertinent infectious, inflammatory, and ischemic etiologies.

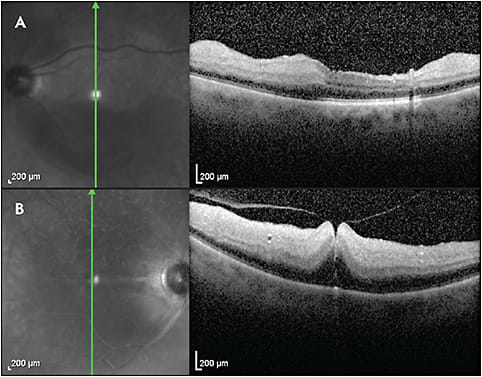

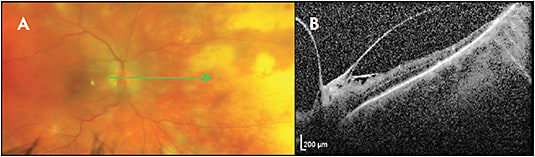

RETINAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSION

Retinal arterial circulation perfuses the inner retina. The outer plexiform layer (OPL) represents a “watershed zone” between retinal and choroidal circulation. Acute retinal arterial occlusions cause hyperreflectivity and thickening of the inner retinal layers (Figure 1). There may also be a loss of identifiable retinal layers, intraretinal fluid, and subretinal fluid.2 In chronic retinal arterial occlusions, thinning of the inner retinal layers, as well as disappearance of the ellipsoid zone (EZ), are possible (Figure 2).3

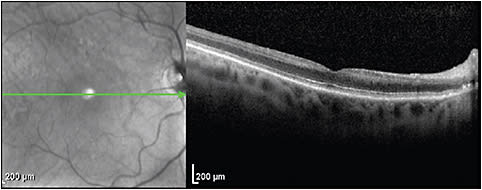

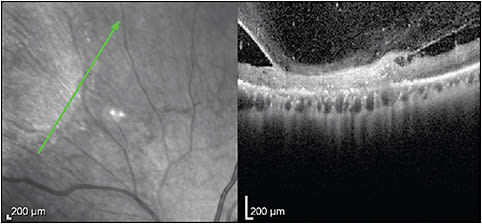

COTTON-WOOL SPOT

Cotton-wool spots (CWS) occur from axoplasmic disruption in the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) secondary to focal ischemia. They acutely present as a focal RNFL thickening and sometimes hyperreflectivity.4-6 Larger CWS may distort the adjacent retinal layers and shadow the outer retinal layers (Figure 3).7 Gomez et al showed that in patients with resolved CWS secondary to HIV, the retinal layers from the inner nuclear layer (INL) to the OPL become thin and that most of the thinning occurs in the ganglion cell layer; the outer nuclear layer (ONL) however may become thickened.6

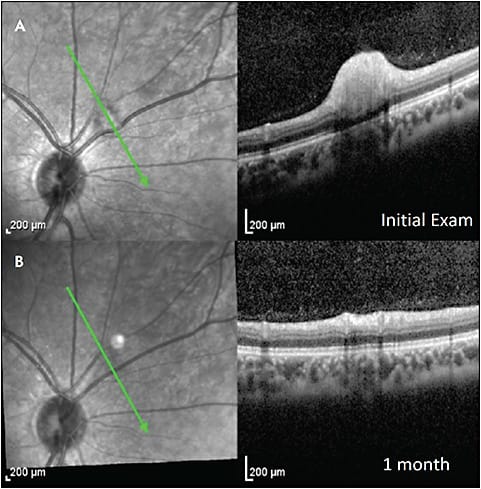

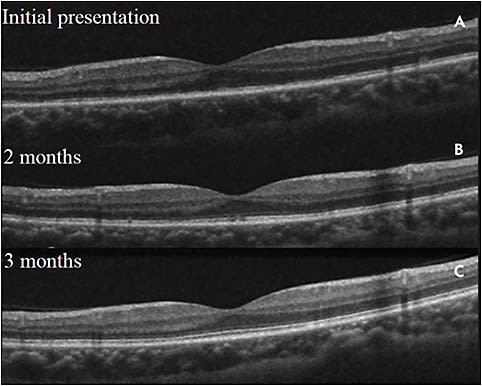

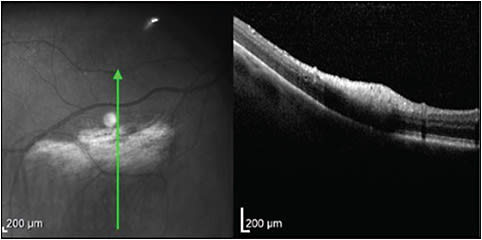

COMMOTIO RETINAE/BERLIN EDEMA

Commotio retinae, also called Berlin edema, is a traumatic retinopathy indicative of damage to the photoreceptors from blunt ocular trauma. In mild cases, there is hyperreflectivity of the EZ without edema, which resolves within days to weeks (Figure 4).8 In severe trauma, there can be acute loss of the EZ with thickening and hyperreflectivity of the overlying retinal layers. Cases of full-thickness retinal hyperreflectivity can progress to atrophic outer retinal layers with hyperreflective aggregates above the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), with lasting vision impairment.9

PROGRESSIVE OUTER RETINAL NECROSIS

Forster et al in 1990 described progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) with a predominance of outer retinal necrosis sparing of the vasculature.10 In early PORN infection, OCT shows inner retinal hyperreflectivity, outer retinal hyporeflectivity, and total retinal thickening.11-15 Progressive outer retinal necrosis is believed to start in the outer retina and progress to involve the full retinal thickness. Margo and Friedman hypothesized that PORN may truly begin in the inner retina, contending that early PORN can resemble arterial occlusion on OCT.16 Intraretinal fluid and schisis can also be seen. Late findings show severe retinal thinning and loss of identifiable retinal layers.

ACUTE RETINAL NECROSIS

Early acute retinal necrosis (ARN) may start as mild hyperreflectivity and thickening in the inner plexiform layer.17 Over days to weeks, the hyperreflectivity and thickening extend to the entire inner retina and can progress to full-thickness retinitis.17-20 Prominent vitritis may limit image quality. Cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membranes, and serous and rhegmatogenous retinal detachments may occur. In the chronic setting, there can be hyporeflectivity, thinning, and loss of identifiability of the retinal layers (Figure 5).17

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS RETINITIS

A longitudinal study by Invernizzi et al in 2018 found 2 broad patterns in active retinitis.21 The first is full-thickness hyperreflectivity and thickening with RPE thickening and choriocapillaris changes; these retinas become thin and lose identifiability of retinal layers with time (Figure 6). The second is cavernous retinitis with inner retinal hyperreflectivity and empty space in the ONL; these are prone to retinal detachments.22 Epiretinal membranes, vitreomacular adhesions, vitreomacular traction, external limiting membrane abnormalities, and EZ zone abnormalities are nonspecific findings in cytomegalovirus retinitis.

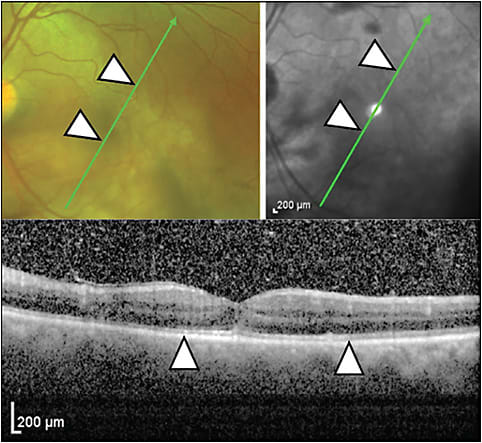

MULTIPLE EVANESCENT WHITE DOT SYNDROME

In multiple evanescent white dot syndrome, the white dots will show patchy hyporeflectivity of the EZ (Figure 7). In recurrent cases, one can see thinning of the ONL.23 Nearly half of patients may have punctate hyperreflective change in the inner choroid on enhanced depth imaging OCT that may precede the EZ disruption.24 Small hyperreflective dots in the ONL can be noted on SD-OCT and are hypothesized to be lipofuscin or damaged photoreceptor debris translocated to the outer retina.25

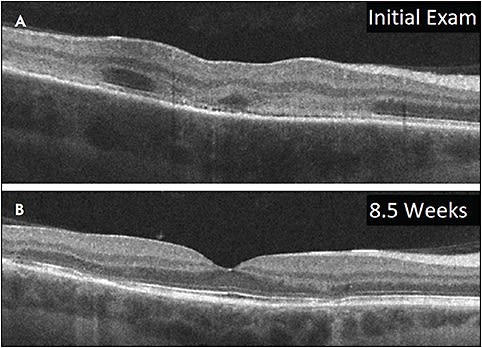

ACUTE POSTERIOR MULTIFOCAL PLACOID PIGMENT EPITHELIOPATHY (APMPPE)

In acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, OCT shows hyperreflectivity which can extend from the OPL to the RPE and can have associated disappearance of the external limiting membrane and EZ (Figure 8). Over time, these changes may resolve, but permanent photoreceptor and RPE atrophy may ensue.26,27 Recovery of the EZ is correlated with improvement of visual acuity.27

MYELINATED NERVE FIBER LAYER

In a patient with myelinated nerve fiber layer, OCT will show dense nerve fiber layer hyperreflectivity in the area of retinal whitening (Figure 9). In severe cases, there can be compression of the adjacent inner retinal layers. These lesions do not change with time.28,29

INTRAOCULAR LYMPHOMA

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma can present in any location, including intravitreal, preretinal, intraretinal, subretinal, and sub-RPE. Infiltrates are hyperreflective and can be focal or diffuse. Vitreous involvement and sub-RPE deposits are the most common, each independently seen in about two-thirds of cases.30 Serial OCT can be useful to monitor disease progression and response to treatment of these lesions.31

CHOROIDAL GRANULOMA

The differential diagnosis for choroidal granulomas can include sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, ocular toxocariasis, cat-scratch disease, focal scleral nodule, choroidal nevi, amelanotic melanoma, choroidal metastasis, and uveal lymphoma.32 They can be typically large homogenous hyporeflective lesions in the choroid, with a smooth dome-shaped change in curvature of the choroid, and can present with subretinal fluid.33-35 Enhanced depth imaging OCT is useful in detecting the change in the lesion over time, but it is not useful in differentiating the etiology of the lesion. Enhanced depth imaging OCT can help evaluate for a focal scleral nodule, which involves the sclera rather than the choroid.32

CONCLUSION

The etiologies of retinal whitening are many and have distinct OCT presentations. Risk factors, clinical history, and multimodal imaging including OCT are instrumental in making the diagnosis and prognosis. RP

REFERENCES

- Staurenghi G, Sadda S, Chakravarthy U, Spaide RF; International Nomenclature for Optical Coherence Tomography (IN•OCT) Panel. Proposed lexicon for anatomic landmarks in normal posterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the IN•OCT consensus. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(8):1572-1578. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.023

- Coady PA, Cunningham ET Jr, Vora RA, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in eyes with acute ischaemic retinal whitening. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(5):586-592. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-304900

- Ahn SJ, Woo SJ, Park KH, Jung C, Hong JH, Han MK. Retinal and choroidal changes and visual outcome in central retinal artery occlusion: an optical coherence tomography study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(4):667-676. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.001

- Kozak I, Bartsch DU, Cheng L, Freeman WR. In vivo histology of cotton-wool spots using high-resolution optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(4):748-750. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.10.048

- Ioannides A, Georgakarakos ND, Elaroud I, Andreou P. Isolated cotton-wool spots of unknown etiology: management and sequential spectral domain optical coherence tomography documentation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1431-1433. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S16272

- Gomez ML, Mojana F, Bartsch DU, Freeman WR. Imaging of long-term retinal damage after resolved cotton wool spots. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(12):2407-2414. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.012

- Mahdjoubi A, Bousnina Y, Barrande G, Bensmaine F, Chahed S, Ghezzaz A. Features of cotton wool spots in diabetic retinopathy: a spectral-domain optical coherence tomography angiography study. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40(7):1625-1640. doi:10.1007/s10792-020-01330-7

- Oh J, Jung JH, Moon SW, Song SJ, Yu HG, Cho HY. Commotio retinae with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2011;31(10):2044-2049. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820f4bb4

- Souza-Santos F, Lavinsky D, Moraes NS, Castro AR, Cardillo JA, Farah ME. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with commotio retinae. Retina. 2012;32(4):711-718. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e318227fd01

- Forster DJ, Dugel PU, Frangieh GT, Liggett PE, Rao NA. Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77012-6

- Almony A, Dhalla MS, Feiner L, Shah GK. Macular optical coherence tomography findings in progressive outer retinal necrosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(6):881. doi:10.3129/i07-171

- Wu CY, Garcia P, Rosen RB. Multimodal imaging of progressive outer retinal necrosis. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(1):41. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2018.10.001

- Broyles HV, Fong JW, Sallam AB. Case series: two cases of herpetic retinitis presenting as progressive outer retinal necrosis in immunocompetent individuals. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2021;23(101119):101119. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101119

- Yeh S, Wong WT, Weichel ED, Lew JC, Chew EY, Nussenblatt RB. Fundus autofluorescence and OCT in the management of progressive outer retinal necrosis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. Published online 2010:1-4. doi:10.3928/15428877-20100216-14

- Chawla R, Tripathy K, Gogia V, Venkatesh P. Progressive outer retinal necrosis-like retinitis in immunocompetent hosts. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216581. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216581

- Margo CE, Friedman SM. Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN): a catchy acronym but is the anatomy correct? The salient observation of Lorenz E. Zimmerman, MD. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(5):651-652. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.120

- Jain A, Anantharaman G, Gopalakrishnan M, Narayanan S. Sequential optical coherence tomography images of early acute retinal necrosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(3):520-522. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_255_19

- Ohtake-Matsumoto A, Keino H, Koto T, Okada AA. Spectral domain and swept source optical coherence tomography findings in acute retinal necrosis. Arbeitsphysiologie. 2015;253(11):2049-2051. doi:10.1007/s00417-015-3051-x

- Murata K, Yamada W, Nishida T, et al. Sequential optical coherence tomography images of early macular necrosis caused by acute retinal necrosis in non-human immunodeficiency virus patients. Retina. 2016;36(7):e55-e57. doi:10.1097/iae.0000000000000972

- Kurup SP, Khan S, Gill MK. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography in the evaluation and management of infectious retinitis. Retina. 2014;34(11):2233-2241. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000218

- Invernizzi A, Agarwal A, Ravera V, Oldani M, Staurenghi G, Viola F. Optical coherence tomography findings in cytomegalovirus retinitis: a longitudinal study. Retina. 2018;38(1):108-117. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001503

- Gupta MP, Patel S, Orlin A, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in macula-involving Cytomegalovirus retinitis. Retina. 2018;38(5):1000-1010. doi:10.1097/iae.0000000000001644

- Nguyen MHT, Witkin AJ, Reichel E, et al. Microstructural abnormalities in MEWDS demonstrated by ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2007;27(4):414-418. doi:10.1097/01.iae.0000246676.88033.25

- Fiore T, Iaccheri B, Cerquaglia A, et al. Outer retinal and choroidal evaluation in multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS): an enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(3):428-434. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1231329

- Pereira F, Lima LH, de Azevedo AGB, Zett C, Farah ME, Belfort R Jr. Swept-source OCT in patients with multiple evanescent white dot syndrome. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2018;8(1):16. Published 2018 Oct 13. doi:10.1186/s12348-018-0159-2

- Oliveira MA, Simão J, Martins A, Farinha C. Management of acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE): insights from multimodal imaging with OCTA. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2020;2020:7049168. doi:10.1155/2020/7049168

- Browne AW, Ansari W, Hu M, et al. Quantitative analysis of ellipsoid zone in acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2020;4(3):192-201. doi:10.1177/2474126420901897

- Ramkumar HL, Verma R, Ferreyra HA, Robbins SL. Myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL): a comprehensive review. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2018;58(4):147-156. doi:10.1097/IIO.0000000000000239

- Chen JJ, Kardon RH. Avoiding clinical misinterpretation and artifacts of optical coherence tomography analysis of the optic nerve, retinal nerve fiber layer, and ganglion cell layer. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016;36(4):417-438. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000422

- Yang X, Dalvin LA, Mazloumi M, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography features of vitreoretinal lymphoma in 55 eyes. Retina. 2021;41(2):249-258. doi:10.1097/iae.0000000000002819

- Liu TYA, Ibrahim M, Bittencourt M, Sepah YJ, Do DV, Nguyen QD. Retinal optical coherence tomography manifestations of intraocular lymphoma. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2012;2(4):215-218. doi:10.1007/s12348-012-0072-z

- Fung AT, Waldstein SM, Gal-Or O, et al. Focal scleral nodule: a new name for solitary idiopathic choroiditis and unifocal helioid choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(11):1567-1577. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.018

- Hage DG, Wahab CH, Kheir WJ. Choroidal sarcoid granuloma: a case report and review of the literature. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2022;12(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12348-022-00309-y

- Salman A, Parmar P, Rajamohan M, Vanila CG, Thomas PA, Jesudasan CAN. Optical coherence tomography in choroidal tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(1):170-172. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.071

- Modi YS, Epstein A, Bhaleeya S, Harbour JW, Albini T. Multimodal imaging of sarcoid choroidal granulomas. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):58. doi:10.1186/1869-5760-3-58