Although pediatric patients account for only 5% to 30% of the uveitis referrals at tertiary care centers, complications are higher in children than adults.1-4 In children, uveitis is difficult to diagnose and manage for multiple reasons. Pediatric disease can be asymptomatic and often is more chronic, recurrent, and treatment resistant than in adults.5 The onset of early disease carries an increased risk of amblyopia and socioeconomic ramifications that accompany visual decline; severe vision loss occurs in approximately 1 in 4 patients.6 The classification of pathology depends on the main site of ocular involvement and helps develop a differential diagnosis as well as investigations into systemic findings (Tables 1 and 2).

ANTERIOR UVEITIS

Anterior uveitis is the most common form of uveitis in children, with rates ranging from 35% to 62%.5,7,8 The most common causes of anterior uveitis include juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (also known as juvenile idiopathic arthritis or JIA), juvenile onset spondyloarthropathies (JOSPAs), juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, Posner-Schlossmann syndrome (PSS), tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU), familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Jabs-Blau syndrome) pediatric sarcoidosis, Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI), poststreptococcal uveitis, trauma, and Beçhet disease.

| Disease | Anterior | Intermediate | Posterior | Panuveitis |

| ANCA associated vasculitis | X | |||

| Bartonella | X | |||

| Beçhet | X | X | X | |

| Endophthalmitis | X | X | X | X |

| FHI | X | |||

| Herpesvirdae | X | X | X | X |

| Jabs-Blau | X | X | X | |

| JAS | X | |||

| JIA | X | |||

| JOSPAs | X | |||

| JXG | X | X | ||

| LCMV | X | |||

| Leukemia | X | X | X | |

| Multiple sclerosis | X | |||

| Pars planitis | X | |||

| Poststreptococcal | X | X | ||

| PSS | X | |||

| Retinoblastoma | X | X | X | |

| Retinitis pigmentosa | X | |||

| Sarcoidosis | X | X | X | X |

| SLE | X | |||

| SO | X | X | X | |

| Syphilis | X | X | X | X |

| TINU | X | X | X | X |

| Toxoplasmosis | X | X | X | |

| Trauma | X | X | X | X |

| Tuberculosis | X | X | X | X |

| VKH | X | X | ||

| WDS | X | X | ||

| ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; FHI, Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis; JAS, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; JOSPAs, juvenile onset spondyloarthropathies; JXG, juvenile xanthogranuloma; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; PSS, Posner-Schlossmann syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SO, sympathetic ophthalmia; TINU, tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis; VKH, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome; WDS, white dot syndrome. | ||||

| Feature | Diseases |

|---|---|

| Joint pain | JIA, JOSPAS, JAS |

| Skin changes | Jabs-Blau, pediatric sarcoidosis, syphilis, SLE, Ricksetta |

| Neurologic changes | MS, Beçhets, VKH, APMPPE, congenital viral, toxoplasmosis, LCMV |

| Trouble breathing | Pediatric sarcoidosis |

| Systemic illness, fever | TB, poststreptococcal syndrome, endophthalmitis |

| Oral or genital ulcers | Syphilis, Beçhet, herpes |

| Trauma | Traumatic iritis, ruptured globe, SO |

| Iris heterochromia | Trauma, IOFB, FHI, leukemia, JXG |

| Iris nodules | Many inflammatory causes, trauma, IOFB, FHI, leukemia, JXG, retinoblastoma |

| APMPPE, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy; FHI, Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis; IOFB, intraocular foreign body; JAS, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis; JIA, juvenile rheumatoid (idiopathic) arthritis; JOSPAS, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; JXG, juvenile xanthogranuloma; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; MS, multiple sclerosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SO, sympathetic ophthalmia; TB, tuberculosis; VKH, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. | |

INTERMEDIATE UVEITIS

Intermediate uveitis impacts between 15% and 30% of pediatric uveitis patients. Most cases in children are idiopathic, also known as pars planitis. When evaluating for causes, inflammatory etiologies, such as JIA, sarcoidosis, and multiple sclerosis, as well as infectious causes, such as toxoplasmosis, syphilis, bartonella, tuberculosis, and endophthalmitis should be considered. Additionally, masquerade syndromes, such as leukemia and retinoblastoma, can cause intermediate uveitis-like changes. Intermediate uveitis tends to be asymptomatic more often in children, making it more difficult to detect. Common findings include vitreous cell, snowballs, peripheral retinal vasculitis, and snowbanks. Chronic snowbanks can lead to peripheral neovascularization and vitreous hemorrhage, and vitreous traction overlying these areas can lead to retinal detachment. Dilation in these patients is essential to rule out posterior involvement, which may be clouded by the overlying vitreous cell and haze.

POSTERIOR AND PANUVEITIS

Posterior uveitis and panuveitis are the least common forms of pediatric uveitis. Infectious uveitis is always a concern in the evaluation for posterior uveitis, and should be ruled out, especially when considering local steroid therapy. The most common causes of infectious uveitis include toxoplasmosis and viral etiologies. Common immune causes include pediatric sarcoidosis, Jabs-Blau syndrome, Beçhet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, sympathetic ophthalmia, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH), and white dot syndromes.

WORKUP

A complete medical history, ocular history, and familial history are necessary, as well as potential exposures, such as trauma or exposure to infectious agents. As a baseline, most patients are evaluated for 3 common etiologies: sarcoidosis, syphilis, and tuberculosis. In children, angiotensin-converting enzyme levels are not as useful because they tend to be higher in children than adults; however, chest x-ray can be helpful. A full examination can require an examination under anesthesia (EUA) and allows for the collection of intraocular samples. Aqueous samples can detect infections or masquerade etiologies. The remainder of this article will detail the common etiologies of uveitis in children.

JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

The most common systemic association with anterior uveitis in children is JIA.9 Chronic, asymptomatic anterior uveitis usually occurs in females with oligoarticular disease, especially when the arthritis sets in before the age of 6, and with positive antinuclear antibodies. In contrast, older males who are HLA-B27 positive tend to develop acute, episodic and symptomatic uveitis. On occasion, patients can also have intermediate findings. Patients generally respond well to topical treatment but can require long-term immunosuppression.

JUVENILE ONSET SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

Juvenile onset spondyloarthropathies include reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease related arthritis, and juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, all of which contribute to anterior uveitis flares in children. A careful review of systems should be done to elucidate systemic symptoms and narrow the diagnosis. Treatment is aimed at both the systemic symptoms and the quiescence of intraocular inflammation.

POSNER-SCHLOSSMANN SYNDROME

Posner-Schlossmann syndrome can also present with episodic increases in intraocular pressure and nongranulomatous anterior-chamber inflammatory episodes. This can be differentiated from other types of anterior inflammation with increased intraocular pressure by its intermittent nature. Other etiologies, such as FHI and viruses tend to have a more chronic presentation.

TUBULOINTERSITITAL NEPHRITIS AND UVEITIS

Another etiology for anterior uveitis is TINU, with the highest incidence of the disease in children and adolescents.10 Although definite diagnosis requires a renal biopsy, several ancillary tests can help anchor the diagnosis, such as urinalysis with elevated urine beta-2 microglobulin, elevated glucose, protein, and red or white blood cells. Additionally, abnormalities in the serum can show blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels. In cases of suspected TINU where the labs are not consistent, it may be prudent to retest the patient in a few months, because uveitis can precede development of kidney issues. Tubulointersitital nephritis and uveitis tends to be a predominantly anterior, bilateral, nongranulomatous process, but it has been reported to have granulomatous and/or posterior involvement. Abnormal renal function can occur in other uveitis conditions, including sarcoidosis, and evaluation should include a nephrologist.

JABS-BLAU SYNDROME AND PEDIATRIC SARCOIDOSIS

Familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Jabs-Blau syndrome) and pediatric sarcoidosis often present with granulomatous anterior inflammation but can also involve the posterior segment with vitritis, chorioretinitis, retinal vasculitis, and optic neuropathy.11 In pediatric sarcoidosis, patients younger than 5 tend to have extrapulmonary involvement, such as skin changes and arthritis, while older children often have multisystemic disease and the typical hilar enlargement. Both pediatric sarcoidosis and Jabs-Blau syndrome are associated with CARD15/NOD2 mutations. The gold standard of diagnosis for sarcoidosis is noncaseating epithelioid granulomas on biopsy.

FUCHS HETEROCHROMIC IRIDOCYCLITIS

Other etiologies for infectious uveitis include FHI, which has been linked to the rubella virus. Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis may cause as many as 7% of the anterior uveitis cases in North America, and onset is often in young adulthood. A strong suspicion for this diagnosis is important in patients who present with unilateral anterior inflammation, elevated intraocular pressure, and stellate keratic precipitates throughout the cornea, especially with a lack of posterior synechiae. Posterior subcapsular cataracts are also common with this disease. When treating FHI, it is important to remember that topical steroids do not usually help the inflammation, but management of the glaucoma is crucial.

POSTSTREPTOCOCCAL SYNDROME

In children with a history of streptococcal pharyngitis, poststreptococcal syndrome uveitis is a possibility, and this can have anterior and posterior findings, such as granulomatous or nongranulomatous anterior uveitis and phlebitis. Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers can be elevated for up to 6 weeks following infection.12 Treatment involves monitoring of the ASO titers and treatment of the streptococcal infection.

TRAUMA

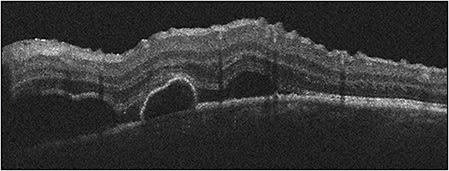

Trauma is a cause of uveitis, with one series attributing almost 5% of cases of uveitis at a referral center to a traumatic incident.13 Traumatic iritis commonly responds to topical steroids; however, in cases of trauma, penetrating ocular injury and intraocular foreign body should be ruled out with appropriate imaging and EUA as necessary (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A 16-year-old patient referred for traumatic iritis. Examination the cornea shows a full-thickness corneal wound that has sealed, with 4+ cell and no view of the lens. Computed tomography showed a retained intraocular foreign body, and the patient underwent a pars plana vitrectomy with foreign body removal and lensectomy.

BEÇHET DISEASE

Beçhet disease most commonly presents with posterior findings, such as retinal vasculitis, but severe anterior uveitis with a hypopyon can occur in unison. Beçhet disease is of utmost importance to recognize, as extraocular manifestations include devastating complications, such as cerebral lesions. Involvement in the pediatric patient is rare, with an average of 5% of cases occurring in children.14 Systemic findings also include ulcers of the mouth and genitals and skin pathergy.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multisystemic disease that can occur in any age group, but in children, the disease tends to be aggressive and can have atypical presentations. Along with the more common retinal vasculitis picture, optic nerve involvement and retinal and choroidal changes have been reported.15

ANTINEUTROPHIL CYTOPLASMIC ANTIBODY ASSOCIATED VASCULITIDES

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides mainly impact small and medium-sized vessels. Etiologies in this group include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). These diseases rarely impact children, and of these, granulomatosis with polyangiitis is the most common, with orbital involvement, episcleritis and scleritis more prevalent than the posterior findings of optic neuropathy and retinal vasculitis.

Tips for Evaluating Pediatric Patients

- Have a low threshold for scheduling an examination under anesthesia.

- In a history of trauma, evaluate thoroughly for a penetrating globe injury, retained foreign body, or possibility of sympathetic ophthalmia.

- Many pediatric uveitis conditions have systemic manifestations, and a physical examination can help elucidate the diagnosis.

- Early referral to a uveitis specialist is encouraged as chronic undertreated inflammation can result in amblyopia and irreversible complications.

SYMPATHETIC OPHTHALMIA

Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is linked to a T-cell response to antigens within the retina and uvea, often in the setting of penetrating ocular trauma or ocular surgery. The exposure of the uveal antigens to the immune system generates inflammation in both eyes. Patients can present with anterior inflammation, posterior inflammation, or panuveitis. Debate exists on the management of the injured eye. Initially, practice patterns dictated that if an eye has no light perception vision, it should be removed within 2 weeks. However, there are reports of inflammation impacting the contralateral eye in shorter periods and inflammation that occurs even after the injured eye was enucleated. Long-term management usually requires immunosuppression.

WHITE DOT SYNDROMES

The conglomerate of white dot syndromes includes inflammatory disorders of the outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and choroid and is comprised of multiple evanescent white dot syndrome, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE), multifocal choroiditis (MFC) with or without panuveitis, punctate inner choroiditis (PIC) and acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. White dot syndromes generally present similarly in adults and children. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome produces a granular macular appearance with tiny subretinal white or yellow lesions, while APMPPE typically has larger lesions that block early on fluorescein angiography. As with adults, neurologic symptoms can accompany the diagnosis of APMPPE and a neurological review of system is essential. MFC and PIC both have distinct subretinal lesions; MFC has vitritis and PIC does not. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy tends to impact young women with an enlarged blind spot and ellipsoid zone changes (Figure 3). Autoflouresence can reveal zonal areas of hyperautofluorescence and hypoautoflouresnce. Patients should be monitored for the development of choroidal neovascular membranes in any of these etiologies.

VOGT-KOYANAGI-HARADA SYNDROME

Like SO, VKH is a T-cell mediated response to retinal and uveal antigens. It occurs more often in Asians, Hispanics, and Native Americans. Systemic findings include central nervous system changes, including aseptic meningitis, and cutaneous manifestations, such as vitiligo and poliosis. Pediatric cases comprise up to 15% of VKH cases and often the disease is more aggressive in children than in adults (Figure 2).16

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Depending on the geographic location, infectious uveitis in children accounts for up to 30% of the of pediatric uveitis cases and is imperative to rule out before starting high-dose steroids.8,17 Pediatric infectious uveitis can be congenital or acquired, and the most common pathogens are toxoplasmosis and viral etiologies.18 When considering viral etiologies, the Herpesviridae family is the most common cause, and these include human herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, human herpes virus, and Epstein-Barr virus.

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Toxoplasmosis can present with a variety of inflammatory findings ranging from anterior uveitis to panueveitis. Especially in cases of suspected congenital infection, a systemic workup is warranted, because the organisms can migrate to neural tissue and rupture. Congenital toxoplasmosis can be asymptomatic to severe, with microphthalmia, hydrocephalus, and developmental issues. Acquired toxoplasmosis is more common than congenital. Typically, reactivation of the infection occurs on the margins of the old chorioretinal scar with overlying inflammation and possible vasculitis. Serum antibody testing for toxoplasmosis as well as ocular PCR can confirm the diagnosis. Multiple treatment regimens aimed at the organism exist.

HERPESVIRIDAE

Common findings with viral infections include ocular hypertension, corneal dendrites, keratic precipitates that do not respect Arlt’s triangle, iritis, and iris atrophy. A dilated eye examination is crucial to rule out retinitis posteriorly, which can sometimes mimic toxoplasmosis. Congenital infections also pose devastating systemic implications. In particular, cytomegalovirus, the most common intrauterine infection, can result in intrauterine growth restriction, sensoneural hearing loss, and microcephaly.19 Congenital varicella-zoster virus can result in cerebral atrophy, seizures, and growth deformities, along with striking white centered chorioretinal scars with a black ring.20 Congenital herpes simplex virus infections can present in 3 ways: (1) with disseminated infection, (2) encephalitis, or (3) skin, eye, and mouth infection. In skin, eye, and mouth infection, conjunctivitis may be the only finding, or posterior involvement can include retinitis, or with punctate white and yellow lesions in the posterior pole along with hemorrhage, or panuveitis.20 An EUA may be necessary in these cases to rule out posterior involvement as well as aid in obtaining intraocular samples to test for viral PCR. Treatment includes systemic and intraocular antivirals, along with cautious use of topical steroids, especially in cases of corneal dendritic involvement.

LYMPHOCYTIC CHORIOMENINGITIS VIRUS

Congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus can result in defects in the central nervous system, developmental issues, and chorioretinal lesions that appear similar to toxoplasmosis. Treatment is usually supportive.

SYPHILIS

With rates of syphilis increasing, the rates of congenital syphilis are also expected to rise. Congenital findings include rhinitis, pneumonia, desquamating skin rash, and deafness, along with any variation of intraocular inflammation including chorioretinitis, retinitis, or retinal vasculitis. Congenital syphilis can also produce a “salt and pepper fundus” in young children. Acquired syphilis also presents in a myriad of ways, but placoid chorioretinitis should raise concern for the disease. Evaluation involves treponemal and nontreponemal testing, and treatment should adhere to the guidelines for central nervous system syphilis.

MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS

Like syphilis, tuberculosis can present in a variety of ways. In particular, granulomatous uveitis, serpigneous like changes, or choroidal granulomas raise the concern for the disease, and quantiferon testing can confirm the diagnosis, along with chest imaging. Antituberculosis therapy should be initiated with infectious disease.

BARTONELLA HENSELAE

While most classically associated with a neuroretinitis, Bartonella henselae also produces a retinitis and choroiditis, along with vascular occlusions. The diagnosis is confirmed by antibody testing, and treatment involves antibiotics such as doxycycline, erythromycin, or azithromycin.21

RICKETTSIA

Rickettsia can cause profound systemic effects, including fevers, rashes, and flu-like symptoms. Evaluating for recent travel or outdoor activities which may predispose to tick bites is essential in these patients. Patients can develop a multitude of posterior uveitis findings, including retinal vasculitis, retinal lesions, and choroiditis. Antibiotics targeting the bacteria, including doxyclycine or macrolides, are typically used.22

TOXOCARA

Classically, the lesions in toxocara are associated with peripheral or central granulomas surrounded by retinal traction and pigmentary changes. Rarely, the patient can have diffuse inflammation without a specific lesion. Serologic testing is of low utility in these patients. Antihelminthic treatment can be helpful, and surgical intervention is necessary in the cases of tractional retinal detachments.23

ENDOPHTHALMITIS

Exogenous endophthalmitis is always a risk of intraocular procedures, while endogenous endophthalmitis usually occurs in the setting of a systemically ill patient. A careful medical and surgical history examination should be done to assess for risk factors. Treatment is aimed at irradiation of systemic risk factors and treating the intraocular pathogens.

DIFFUSE UNILATERAL SUBACUTE NEURORETINITIS

Subretinal nematodes, such as Bayliascaris procyonis, can cause widespread retinal degeneration and atrophy following areas of outer retinal and choroidal multifocal lesions, vitritis, and optic disc edema followed by pallor. Ideally, identification of the worm on fundoscopy and treating with photocoagulation is the preferred treatment, but albendazole can also be used.

MASQUERADE

Masquerade syndromes can often muddy the differential diagnosis for a child, particularly in the cases where examination is difficult or limited in the clinic. As with all cases of uveitis, a careful medical history, family history, and dilated eye examination are necessary to help make the diagnosis.

LEUKEMIA

Leukemia is the most common malignancy of childhood, and anterior inflammation most often occurs in the setting of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Patients can have either unilateral or bilateral anterior chamber involvement, with a pseudohypopyon (usually creamy white in color with shaggy material that does not neatly settle or has a lumpy appearance). Patients can also present with a hyphema. These can initially respond to topical steroids but will fail to resolve the collection completely. Iris infiltration can result in iris nodules, heterochromia, or elevated intraocular pressure from trabecular meshwork invasion.24 An anterior chamber collection with cytologic evaluation can help make the diagnosis with the help of oncology for further management.

RETINOBLASTOMA

Retinoblastoma remains the most common intraocular malignancy of childhood, usually impacting children under the age of 5 years. Anterior chamber inflammation can either occur in setting of tumor necrosis or from circulating malignant cells. Uveitis has been reported in up to 40% of patients with retinoblastoma, and iris infiltration has also been noted.25 The enrollment of an ocular oncologist and systemic oncologist are mandatory in the management of these patients.

JUVENILE XANTHOGRANULOMA

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is primarily a cutaneous disorder, but involvement of ocular structures can include the uvea, cornea, conjunctiva, retina, and optic nerve. Patients with juvenile xanthogranuloma are usually under the age of 2 years. Anterior-chamber involvement can involve circulating white blood cells, hyphema, iris nodules, heterochromia, and/or elevated intraocular pressure from invasion of the angle.26 Aqueous samples can aid in the diagnosis, with histology showing various inflammatory cells, foamy histocytes, and staining with Oil Red O for fatty deposits.

RETINITIS PIGMENTOSA

Retinitis pigmentosa has an overlapping clinical picture with chronic uveitis, including posterior subscapular cataracts, mild vitreous cell, cystoid macular edema, and peripheral perivascular pigmentary changes. Electroretinogram can help elucidate the diagnosis, and fluorescein angiography should not have an inflammatory pattern of leakage.

SUMMARY

The differential for pediatric uveitis is large. However, careful attention to location, onset, exposures, and systemic manifestations can help narrow the diagnosis. RP

REFERENCES

- Cunningham ET Jr. Uveitis in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8(4):251-261. doi:10.1076/ocii.8.4.251.6459

- Nagpal A, Leigh JF, Acharya NR. Epidemiology of uveitis in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48(3):1-7. doi:10.1097/IIO.0b013e31817d740e

- BenEzra D, Cohen E, Maftzir G. Uveitis in children and adolescents. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(4):444-448. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.050609

- Edelsten C, Reddy MA, Stanford MR, Graham EM. Visual loss associated with pediatric uveitis in english primary and referral centers. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(5):676-680. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02148-7

- Chan NS, Choi J, Cheung CMG. Pediatric uveitis. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2018;7(3):192-199. doi:10.22608/APO.2018116

- Thorne JE, Suhler E, Skup M, et al. Prevalence of noninfectious uveitis in the United States: a claims-based analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(11):1237-1245. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.3229

- Rosenberg KD, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Ocular complications of pediatric uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(12):2299-2306. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.014

- Smith JA, Mackensen F, Sen HN, et al. Epidemiology and course of disease in childhood uveitis [published correction appears in Ophthalmology. 2011 Aug;118(8):1494]. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(8):1544-1551.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.002

- Petty RE, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Arthritis and uveitis in children. A pediatric rheumatology perspective. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(6):879-884. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00104-1

- Clive DM, Vanguri VK. The syndrome of tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis (TINU). Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):118-128. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.013

- Hoover DL, Khan JA, Giangiacomo J. Pediatric ocular sarcoidosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;30(4):215-228. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(86)90118-9

- Ur Rehman S, Anand S, Reddy A, et al. Poststreptococcal syndrome uveitis: a descriptive case series and literature review. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(4):701-706. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.12.024

- Rosenbaum JT, Tammaro J, Robertson JE Jr. Uveitis precipitated by nonpenetrating ocular trauma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(4):392-395. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76245-2

- Batu ED. Diagnostic/classification criteria in pediatric Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(1):37-46. doi:10.1007/s00296-018-4208-9

- Brunner HI, Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MD, Silverman ED. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(2):556-562. doi:10.1002/art.23204

- Khalifa YM, Bailony MR, Acharya NR. Treatment of pediatric Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome with infliximab. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(3):218-222. doi:10.3109/09273941003739910

- Kump LI, Cervantes-Castañeda RA, Androudi SN, Foster CS. Analysis of pediatric uveitis cases at a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(7):1287-1292. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.044

- Hettinga YM, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Rothova A, de Boer JH. Infectious involvement in a tertiary center pediatric uveitis cohort. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(1):103-107. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305367

- Mets MB, Chhabra MS. Eye manifestations of intrauterine infections and their impact on childhood blindness. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(2):95-111. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.12.003

- Yoser SL, Forster DJ, Rao NA. Systemic viral infections and their retinal and choroidal manifestations. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;37(5):313-352. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(93)90064-e

- Biancardi AL, Curi AL. Cat-scratch disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(2):148-154. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.833631

- Kahloun R, Gargouri S, Abroug N, et al. Visual loss associated with rickettsial disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(5):373-378. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.848907

- Woodhall D, Starr MC, Montgomery SP, et al. Ocular toxocariasis: epidemiologic, anatomic, and therapeutic variations based on a survey of ophthalmic subspecialists. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(6):1211-1217. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.013

- Sharma T, Grewal J, Gupta S, Murray PI. Ophthalmic manifestations of acute leukaemias: the ophthalmologist’s role. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(7):663-672. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6701308

- Stafford WR, Yanoff M, Parnell BL. Retinoblastomas initially misdiagnosed as primary ocular inflammations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82(6):771-773. doi:10.1001/archopht.1969.00990020763008

- DeBarge LR, Chan CC, Greenberg SC, McLean IW, Yannuzzi LA, Nussenblatt RB. Chorioretinal, iris, and ciliary body infiltration by juvenile xanthogranuloma masquerading as uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;39(1):65-71. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80046-3.