Floaters are a common complaint in a retina practice, as they can be very concerning to patients. Symptoms range from a sense of bothersome insects to blurred vision. These entopic phenomena require intervention that varies from simple reassurance to urgent laser or surgical repair, or even workup for potentially lethal systemic etiologies. An organized methodology of differential diagnosis, examination, and testing — updated with recent literature — benefits the retinal physician and patient alike. Broadly, the pathologic causes of floaters may be subdivided into 3 categories based on the specific cause of the floater: (1) posterior vitreous detachment, (2) hemorrhage without retinal tear, or (3) lymphocytes. These etiologies are reviewed below.

POSTERIOR VITREOUS DETACHMENT

Posterior vitreous detachment is the most common source of symptomatic floaters. By the ninth decade of life, 87% of patients have undergone posterior vitreous detachment, increasing steadily from 24% in the sixth decade.1 Classically, patients complain of increased floaters with a central floater temporal to the fovea corresponding to the location over the optic nerve. The flashes seen by patients, often explained as the vitreous pulling on the retina as it releases, are thought to initiate from mechanosensitive potassium channels in the retinal ganglion cells.2 Significant historical features about which to inquire include trauma or high myopia. During careful scleral-depressed examination with overlapping views, the physician should note lattice degeneration and other peripheral pathology. Other peripheral features impact likelihood of retinal tear. Most importantly, 14% of all patients evaluated with symptomatic flashes and floaters ultimately were found to have a retinal tear in a meta-analysis of presenting patients, whereas the presence of hemorrhage significantly increases the likelihood.3-7 If the retinal tear is chronic, loosed retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells can be found intermixed with the vitreous hemorrhage, producing a positive “tobacco dust” Shafer sign. This contributes further to the sense of floaters in some patients.

HEMORRHAGE WITHOUT RETINAL TEAR

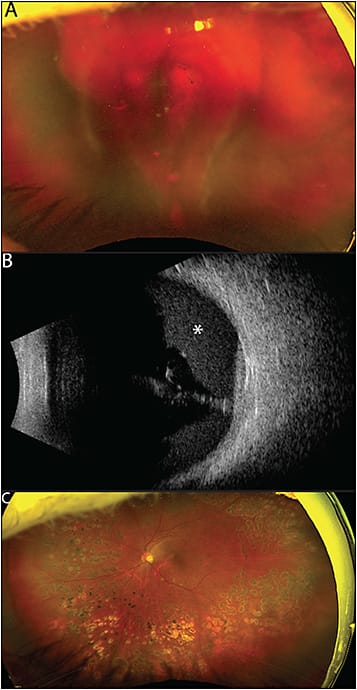

The presence of hemorrhage devoid of retinal tear, as often seen in diabetic vitreous hemorrhage, can present simple yet challenging diagnostic dilemmas for the practicing clinician. A frequent presentation for the patient progressing to diabetic retinopathy, vitreous hemorrhage is even more common among patients already on hemodialysis. A recent retrospective review of 145 eyes found that 23.4% of patients on hemodialysis presented with a vitreous hemorrhage within 1 year, with that rate being reduced by prompt panretinal photocoagulation.8 Often the clinical question in mind is twofold for a new patient with vitreous hemorrhage: is there an occult break or retinal detachment in the peripheral retina, and what degree of posterior traction is obscured by this vitreous hemorrhage? To augment a careful examination with slit lamp and indirect ophthalmoscopy, widefield funduscopic photography and B-scan ultrasonography may prove useful.

The vitreous hemorrhage featured in Figure 1 demonstrates utility of B-scan ultrasonography in preoperative evaluation of dense diabetic vitreous hemorrhage. In this case, a 56-year-old type 1 diabetic female patient presented with acute vision loss that began with floaters and progressed to decreased acuity of count fingers at 2 feet, down from 20/60 baseline in the left eye. B-scan ultrasonograpny helped exclude an occult retinal tear or component of significant posterior tractional retinal detachment, allowing for safe series of intravitreal injections in attempt of conservative management. Further, the subhyaloidal compartment of this patient’s hemorrhage can be seen clearly in this case. After three months without resolution, vitrectomy was performed without issue and panretinal photocoagulation was completed with endolaser. Two months postoperatively, she returned to baseline 20/60 vision and was happy with the outcome.

A recent review of 111 eyes with vitreous hemorrhage were evaluated by B-scan ultrasonography to determine presence of tractional retinal detachment. Of the 88 eyes with vitreous hemorrhage caused by diabetes, 26.2% were determined to have tractional retinal detachment,9 which can significantly change surgical planning. B-scan ultrasonography is crucial to consider when planning preoperatively to minimize risk of iatrogenic damage to a covertly elevated retina during vitrectomy. Details about the position of the hemorrhage, such as whether subhyaloidal hemorrhage is present, can also be determined prior to the operating room. If the retina cannot be sufficiently visualized on examination with light, ultrasound can determine anatomic features to the greatest extent possible at initial presentation.

LYMPHOCYTES

The third category of vitreous opacity, often perceived as floaters by patients, includes infiltrating lymphocytes from a variety of etiologies. Intermediate and posterior uveitic entities result in condensation of white blood cells, which can coalesce into typical “string of pearls” configuration along with snowballs and snowbanks in the peripheral anterior retina and vitreous. The wide list of these underlying etiologies is beyond the scope of this review. Bacterial endophthalmitis can typically be distinguished from other etiologies based on prior surgery or injection as well as more robust inflammation and ocular pain. If the patient has painless endophthalmitis, sterile postinjection inflammation as well as fungal etiologies come to the fore. Aspergillus has been noted recently as the cause of a painless presentation in the setting of an aspergilloma.10

Neoplastic processes also present in this third category as painless floaters and subsequent blurred vision in the setting of vitreoretinal lymphoma (VRL; formerly referred to as primary intraocular lymphoma). This critical cause of floaters is associated with high mortality if associated with central nervous system involvement.11,12 The most common underlying etiology of VRL is non-Hodgkin diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, comprising 95% of intraocular lymphoma cases.13 Easily overlooked on initial presentation with vitritis and symptomatic floaters, the clinician is wise to recall that VRL typically presents in the fifth and sixth decade of life, but can present in younger patients as well. Bilateral presentation, albeit usually asymmetric, is common in 67% to 83% of cases,14 and should prompt reconsideration of a vitritis differential diagnosis if unresponsive to antibiotic or steroid therapy.

SUMMARY

There are a variety of underlying etiologies that can present as entopic phenomena, specifically as floaters. While there are causes not highlighted in this review, such as asteroid hyalosis, pathologic causes may be considered within the diagnostic framework of (1) posterior hyaloid face and Weiss ring, (2) blood or loosed RPE cells, or (3) leukocytes. Because retina specialists always endeavor to explain a patient’s vision with diagnoses, the treating physician must discern the cause of the patient’s floaters because management ranges from careful observation to urgent surgery or even workup for lethal systemic pathology. As always, careful history and examination bear the most fruit in these patient encounters, at times supplemented with targeted imaging such as widefield fundus photography and B-scan ultrasound. With this framework in mind, the retina specialist may proceed with confidence the next time a patient presents with bothersome floaters. RP

REFERENCES

- Hikichi T, Hirokawa H, Kado M, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of posterior vitreous detachment in whites and Japanese. Ophthalmic Surg. 1995;26(1):39-43.

- Xia J, Lim JC, Lu W, Beckel JM, Laties AM, Mitchell CH. Mechanosensitive channels in isolated rat retina ganglion cells: response to strain from within neurons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(14):6603.

- Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment?. JAMA. 2009;302(20):2243-2249. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1714

- Boldrey EE. Risk of retinal tears in patients with vitreous floaters. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96(6):783-787. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71924-5

- Brod RD, Lightman DA, Packer AJ, Saras HP. Correlation between vitreous pigment granules and retinal breaks in eyes with acute posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(9):1366-1369. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32124-9

- Sharma S, Walker R, Brown GC, Cruess AF. The importance of qualitative vitreous examination in patients with acute posterior vitreous detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(3):343-346. doi:10.1001/archopht.117.3.343

- Tanner V, Harle D, Tan J, Foote B, Williamson TH, Chignell AH. Acute posterior vitreous detachment: the predictive value of vitreous pigment and symptomatology. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(11):1264-1268. doi:10.1136/bjo.84.11.1264

- Kameda Y, Hanai K, Uchigata Y, Babazono T, Kitano S. Vitreous hemorrhage in diabetes patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy undergoing hemodialysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(3):688-692. doi:10.1111/jdi.13161

- Demir G, Arici M, Alkin Z. Preoperative evaluation of tractional retinal detachment with B-mode ultrasonography in diabetic vitreous hemorrhage. Beyoglu Eye J. 2021;6(1):49-53. doi:10.14744/bej.2021.58561

- Kiang L, Pirouz A, Grant S, Adrean SD, Malihi M, Lin P. Aspergillus endophthalmitis resulting in development of retinal aspergilloma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017;48(8):680-683. doi:10.3928/23258160-20170802-13

- Carbonell D, Mahajan S, Chee SP, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(3):507-520. doi:10.1080/09273948.2021.1878233

- Chan CC, Sen HN. Current concepts in diagnosing and managing primary vitreoretinal (intraocular) lymphoma. Discov Med. 2013;15(81):93-100.

- Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36(6):564-578. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01843.x

- Sagoo MS, Mehta H, Swampillai AJ, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(5):503-516. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.12.001