Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy and macular edema (DR/DME), and retinal vein occlusion (RVO) significantly impact functioning and quality of life and thus have a substantial global burden.1–5 Effective management of these conditions requires good patient adherence to available standard-of-care treatment, including intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF therapy. Nevertheless, research suggests that nearly one-quarter of patients treated for AMD6 or DR7 may be lost to follow-up beyond 12 months.

Gaps in patient understanding of the importance of treatment and patient-provider communication can be a barrier to patient adherence to therapy.8 Shared decision-making (SDM) is an approach through which clinicians and patients work collaboratively work to evaluate the available evidence and make care-related decisions. Significantly, SDM depends on informing patients about their options and puts their priorities and values front and center.9 Evidence shows that the use of SDM strengthens the positive impact of the patient-provider relationship on patient adherence to therapy.8

This brief report summarizes survey findings regarding gaps in understanding care among patients with AMD, RVO, or DR/DME, areas of alignment and discordance between patients and providers, and the impact of a patient-provider collaborative learning program aimed at improving SDM.

STUDY DESIGN

This study included patient-provider collaborative learning sessions in retinal centers with significant AMD, DR, and RVO patient populations in geographically diverse regions of the United States. The AMD patient-provider sessions were held in person, whereas the RVO and DR/DME sessions were held virtually due to COVID-19 restrictions. The AMD and RVO sessions were held at 5 clinics each, while the DR/DME sessions were conducted at 6 participating clinics. Each session had multiple patients, with about 10 to 15 patients per group. The sessions were held during separate hours (not during regular exam visits) and arranged during lunch or after hours in each clinic or virtually.

Participants

Clinics enrolled in the study invited members of their patient community and their retina care teams to participate in surveys and group education. Each patient attended one educational session. Retina care teams included retina specialists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and others who provide health care at the respective clinics. Providers participating in the educational session received continuing education credits. The participating patient and provider demographics are presented in Table 1.

| AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION | RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION | DIABETIC RETINOPATHY/DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA | |

| Participating clinics | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Number | 51 | 53 | 120 |

| Average age | 78 | 63 | 54 |

| Female sex (%) | 26 (51%) | 36 (68%) | 68 (57%) |

| Provider characteristics | |||

| Number | 45 | 8 | 35 |

| Specialty (%) | Retina specialist: 17 (38%)Nurse: 24 (53%) Other: 4 (9%) |

Retina specialist: 6 (75%) Nurse practitioner: 2 (25%) |

Retina specialist: 14 (40%) Nurse practitioner/physician assistant: 10 (11%) Nurse: 4 (29%) Other: 7 (20%) |

| Average years caring for AMD/RVO/DR-DME patients (range) | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Average number of AMD/RVO/DR-DME patients seen per week | 46 | 13 | 60 |

Educational Format

An expert retina specialist conducted the 1-hour collaborative face-to-face group session during lunch or after hours in each clinic or virtually. The instructional design consisted of a patient-centered digital slide presentation with discussion opportunities for the participants. The sessions were designed to be informal and interactive to increase participation from patients. Educational topics included understanding the condition, goals, risks, and benefits of treatment; SDM to improve visual outcomes; and overcoming challenges in medication adherence.

Surveys

Participants completed a pre-survey before the group sessions and a post-survey after. The patient pre-surveys included questions on knowledge about their retinal condition, communication with their retina specialist, and their views about SDM. The provider pre-survey asked about patient care, communication with patients, and SDM. The post-surveys assessed the impact of learning, any changes in perceptions and attitudes, and action plans participants intend to set.

RESULTS

Patient-identified vs Provider-identified Challenges

The challenge reported most often by patients was difficulty understanding their treatment options (36% of AMD patients; 47% of RVO patients; 39% of DR/DME patients). The top 2 provider-identified challenges were patient adherence to anti-VEGF therapy (33% in AMD; 38% in RVO; 36% in DR/DME) and engaging patients in SDM (13% in AMD; 37% in RVO; 25% in DR/DME).

Patient and Provider Perspectives on Anti-VEGF Nonadherence

When asked the main reason for stopping anti-VEGF injection in the past (without plans to switch to a new anti-VEGF injection), AMD (45%) and RVO (43%) patients chose perceived lack of vision improvement as the main reason. In comparison, DR/DME patients (36%) reported stopping anti-VEGF treatment due to side effects. But, in all 3 disease areas, providers believed that treatment fatigue was the main reason for patients to stop anti-VEGF therapy.

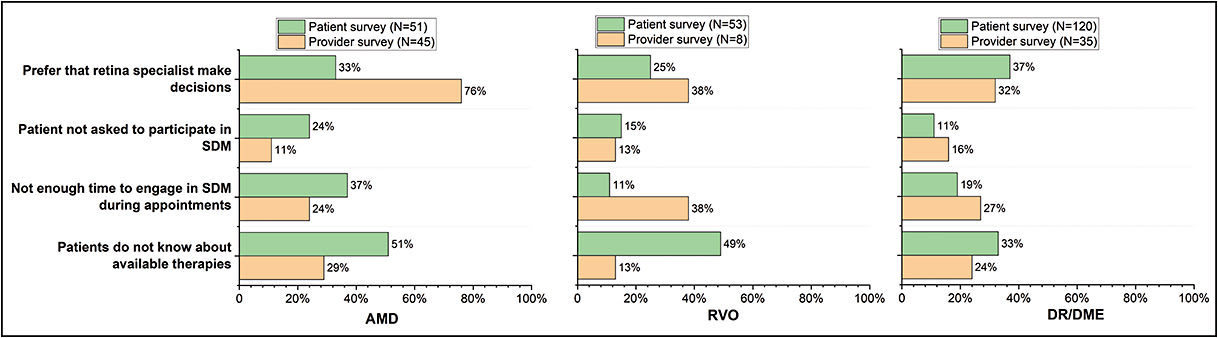

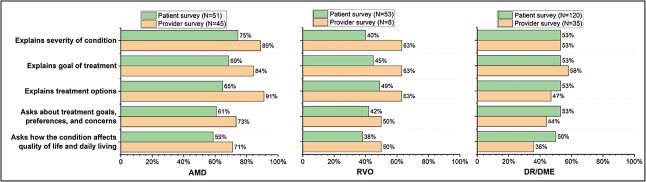

Patient-identified vs Provider-identified Preferences in Decision-making

In the AMD setting, 76% of providers reported they think patients would prefer their specialist to make the decisions, but only 33% of patients said they felt this way. Conversely, 32% of DR/DME providers believe patients want the specialist to make treatment decisions, an opinion that was reflected by 37% of patients. Among RVO patients, 24% reported they prefer their specialist to make the decisions, while 37% of the providers felt that was the case (Figure 1).

Patient-identified vs. Provider-identified Engagement in SDM

In both the AMD and RVO groups, providers were consistently more likely than patients to say that they had engaged in shared decision-making activities. However, this pattern did not appear in the DR/DME group (Figure 2).

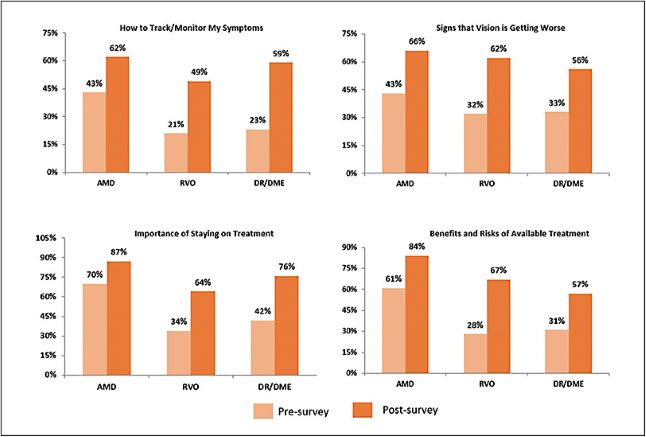

Impact of Educational Session

Patients reported that the program increased their knowledge base in all 3 disease categories. This included significant increases in the proportion of patients who reported increased knowledge on how to track their symptoms, how to identify signs their vision was getting worse, the importance of staying on treatment, and the benefits/risks of available treatment (Figure 3).

Following the program, 81% of AMD patients, 38% of RVO patients, and 57% of DR/DME patients reported that they planned to talk with their provider about their treatment options. The program also increased the proportion of AMD patients (69% to 83%), RVO patients (22% to 48%), and DR/DME patients (52% to 89%) who planned to tell their providers their concerns about treatment.

Providers expressed commitment to conducting small group education sessions with their patients following the program (63% in AMD; 100% in RVO; 36% in DR/DME sessions) and engaging their patients more frequently in SDM (46% of AMD providers; 62% of DR/DME providers). In addition, 29% of providers in the AMD sessions, 60% in the RVO sessions, and 46% in the DR/DME sessions pledged to train colleagues to conduct small-group educational sessions.

DISCUSSION

The goals of the educational program were to enhance cooperation and communication between retina providers and their patients and identify areas of alignment, discordance, and gaps in care. These collaborative sessions were also an opportunity for providers to understand their patients’ knowledge, beliefs, and challenges.

The surveys revealed that many patients with retinal diseases desire greater knowledge about their condition and treatment options. Addressing this knowledge gap can be a significant step to improve patient communication. While there are various sources for gaining information, patients often prefer getting health-related information directly from their providers. For example, in a previously published survey of more than 7,000 patients at a tertiary eye care center, a majority of patients (55%) said that they preferred learning about eye health and disease in a one-on-one session with their provider and through resources recommended by them (both printed and websites).10 The same study also reveals that patients learning from their provider were older (average age 59 years) than patients learning from the internet (average age 49 years).

Retina providers can also supplement verbal communication with patient education materials, such as informational handouts and patient-oriented websites. However, providers need to be mindful of the readability of these materials, because they often convey complex information at an advanced reading level.11 A systematic review of 13 studies that evaluated a total of 950 educational materials revealed that ophthalmic patient education materials are consistently written at a level that is too high for many patients to understand.12

Additionally, retina providers could connect their patients with patient education and support groups, which are usually offered though medical organizations, foundations, and patient advocacy groups. These in-person and online groups create multiple forums where patients can share their stories and engage in educational and informational meetings. Patients with vision impairment who participate in support groups and rehabilitation feel successful in coping with their vision loss and generally have a positive outlook on life.13

These surveys also point to discordance between patients with retinal diseases and their providers regarding patient concerns about their condition, therapy, and barriers to care. Many AMD and RVO patients expressed their interest in SDM, but more DR/DME patients preferred their providers to make treatment decisions. The DR/DME group results conflict with a previous survey of more than 800 patients that showed that most DR patients (74.3%) preferred SDM between ophthalmologist and patient.14 The same study also indicates that older DR patients with low educational attainment wanted to delegate the decision-making process to the ophthalmologist.

Although many patients and providers in this study believe in the benefits of SDM, significant barriers exist to its effective implementation, such as patients’ lack of knowledge about the condition and treatment options, communication barriers, and time restrictions. Our collaborative learning program designed to promote SDM showed an increase in patients’ knowledge base related to their disease and its treatment. The patients also expressed increased willingness to be more involved in their care decisions. Although our group-learning model requires investing time and effort for the participating clinics and their patients, it can be helpful for busy retina practices where providers feel that appointment times are short to engage in patient education. Selecting appropriate patients who would most benefit from this or other direct educational methods must be considered. Older patients and adults with lower health literacy are especially vulnerable to inadequate collaboration with providers15 and may be best suited for this type of learning intervention.

LIMITATIONS

This analysis was conducted over multiple clinics in the United States and comprised a diverse sample of patients and retinal specialists. Nevertheless, it is limited by its small sample size and the self-reported nature of its findings. The surveys designed to assess gaps in care and patient and provider discordances are not validated research tools. Selection bias may also affect the study results, because there were no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria for clinics and participants. Because the participation in the learning sessions was voluntary, there could be an over-representation of patients and providers who wish to collaborate and partake in SDM.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that a collaborative patient-provider learning program designed to promote SDM can improve patients’ knowledge about their condition and providers’ understanding of barriers to care from their patients’ perspectives. In addition, a better understanding among patients of the reasons to stay on treatment and among providers of the challenges their patients face may promote better adherence to therapy and a more positive patient-provider relationship. RP

REFERENCES

- Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Strategies to tackle the global burden of diabetic retinopathy: from epidemiology to artificial intelligence. Ophthalmologica. 2020;243(1):9-20. doi:10.1159/000502387

- Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2014;2(2). doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1

- Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40-50. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024

- Song P, Xu Y, Zha M, Zhang Y, Rudan I. Global epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. J Glob Health. 2019;9(1). doi:10.7189/jogh.09.010427

- Laouri M, Chen E, Looman M, Gallagher M. The burden of disease of retinal vein occlusion: review of the literature. Eye. 2011;25(8):981. doi:10.1038/EYE.2011.92

- Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up among patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration who received intravitreal anti–vascular endothelial growth factor injections. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(11):1251-1259. doi:10.1001/JAMAOPHTHALMOL.2018.3578

- Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy after panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal anti-vegf injections. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(9):1386-1392. doi:10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2018.02.034

- Deniz S, Akbolat M, Çimen M, Ünal Ö. The mediating role of shared decision-making in the effect of the patient-physician relationship on compliance with treatment. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:23743735211018064. doi:10.1177/23743735211018066

- Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301-312. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010

- Rosdahl JA, Swamy L, Stinnett S, Muir KW. Patient education preferences in ophthalmic care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:565-574. doi:10.2147/PPA.S61505

- Muir KW, Lee PP. Health literacy and ophthalmic patient education. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55(5):454-459. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.03.005

- Williams AM, Muir KW, Rosdahl JA. Readability of patient education materials in ophthalmology: a single-institution study and systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:133. doi:10.1186/s12886-016-0315-0

- Van Zandt PL, Van Zandt SL, Wang A. The role of support groups in adjusting to visual impairment in old age. J Vis Impair Blind. 1994;88(3):244-252. doi:10.1177/0145482X9408800309

- Marahrens L, Kern R, Ziemssen T, et al. Patients’ preferences for involvement in the decision-making process for treating diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):139. doi:10.1186/s12886-017-0526-z

- Graumlich JF, Wang H, Madison A, et al. Effects of a patient-provider, collaborative, medication-planning tool: a randomized, controlled trial. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2129838. doi:10.1155/2016/2129838