Standard of care for patients with symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment?

A patient is referred to you with photopsias and floaters; does this sound familiar?

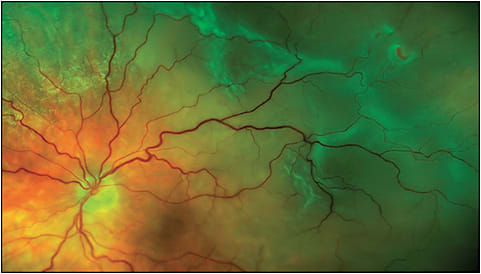

With the knowledge that between 8% and 46% of patients with acute posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) symptoms have a retinal tear,1-5 you are tasked with finding and treating any retinal tear to prevent a vision-threatening retinal detachment. An exam of the vitreous base is indicated, because this is where the vast majority of tractional retinal tears occur induced by the vector forces occurring during an acute PVD. The vitreous base examination is critical, because this 3- to 6-mm diameter region that straddles the ora serrata is where the vitreous collagen fibrils firmly attach at right angles with an intervening extracellular matrix to the internal limiting membrane of the peripheral retina6 — tractional forces here may overcome retinal integrity forces, resulting in a retinal tear (Figure 1).

Does this dilated fundus examination of the vitreous base require the performance of a scleral depressed examination with binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy? Scleral depression allows us to examine the peripheral retina in profile, highlighting an elevated flap tear in an area of vitreoretinal traction. Is scleral depression a “standard of care” (ie, what a similarly trained practitioner would do under similar circumstances7,8) maneuver in these circumstances, or would other methods (eg, 3-mirror or widefield lens ophthalmoscopy with the slit lamp biomicroscope) suffice?

Many have interpreted the “Preferred Practice Pattern” (PPP) statement of the American Academy of Ophthalmology on posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks and lattice degeneration9 to declare that indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression is a requirement and a necessity for correct diagnosis of patients with photopsias and floaters, to rule in or rule out the presence of an acute retinal tear. This position, especially if taken by leaders in the field, obviously has important medicolegal implications- and could very well be cited in the future by lawyers representing plaintiff patients in legal actions if documentation of scleral depression is not found in the medical record.

A recent diagnostic error study by the Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company (OMIC) found that 38% of all claims closed between 2008 and 2014 involved a retinal condition: retinal detachment accounted for 79% of those retina claims and 48% of the payments.10 Therefore, the issue addressed in this column is an important one.

Because there are no published randomized controlled studies comparing indirect ophthalmoscopy with or without scleral depression for diagnoses in this clinical scenario, what other data do we have to address the issue?11 The PPP statement notes that scleral depression in this circumstance is supported by the “lowest strength of evidence.”9 Despite this, should the performance of scleral depression in conjunction with binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy in this situation be considered the “standard of care?” If the presence of a retinal tear or detachment appears likely to have been missed at a particular visit where there is no documentation of scleral depression, is this sufficient to prove “negligence?”

We are fortunate to have the commentary of Seenu M. Hariprasad, MD, Shui-Chin Lee Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Science and chief of the vitreoretinal service and director of clinical research at the University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences; and Pauline T. Merrill, MD, uveitis section director at Rush University and a vitreoretinal surgeon with Illinois Retina Associates, S.C., in Chicago, to address this important issue.

REFERENCES

- Tasman WS. Posterior vitreous detachment and peripheral retinal breaks. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1968;72(2):217-224.

- Tani P, Robertson DM, Langworthy A. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment without macular involvement treated with scleral buckling. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90(4):503-508.

- Coffee RE, Westfall AC, Davis GH, Mieler WF, Holz ER. Symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment and the incidence of delayed retinal breaks: case series and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):409-413.

- Benson WE, Grand MG, Okun E. Aphakic retinal detachment. Management of the fellow eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(4):245-249.

- Scott IU, Smiddy WE, Merikansky A, Feuer W. Vitreoretinal surgery outcomes. Impact on bilateral visual function. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(6):1041-1048.

- Hogan MJ. The vitreous, its structure, and relation to the ciliary body and retina. Proctor award lecture. Invest Ophthalmol. 1963;2:418-445.

- Sampson LF. Encyclopedia of Health Services Research, vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009.

- Walston-Dunham B. Medical Malpractice Law and Litigation. United States: Thomas Learning, Inc; 2006.

- AAO Retina/Vitreous PPP Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Preferred practice pattern. Posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration. San Francisco, California: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at aao.org/ppp .

- Menke AM. Failure to diagnose retinal detachments. The OMIC Digest. 2017;27(1):1,4,5,7. Available at https://www.omic.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Digest-No-1-10-10-17-entire-for-web-1.pdf

- Shukla SY, Batra NN, Ittiara ST, Hariprasad SM. Reassessment of scleral depression in the clinical setting. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):2360-2361.

Comments from Seenu M. Hariprasad, MD

Shui-Chin Lee Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Science and chief of the vitreoretinal service and director of clinical research at the University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences

A timely and thorough dilated fundus exam with indirect ophthalmoscopy is of utmost importance in detecting important peripheral vitreoretinal pathology in symptomatic patients. Is the “standard of care” to perform a dilated fundus exam with scleral depression in every patient? There is little objective evidence in the literature supporting that scleral depression improves the detection of peripheral vitreoretinal pathology. In 2008, the American Academy of Ophthalmology published guidelines regarding the examination and treatment of patients with symptoms of peripheral retinal pathology. An expert panel consisting of retina specialists extensively reviewed the literature at the time and formulated the PPP for examination and treatment of patients with symptoms of peripheral retinal pathology. Indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression was considered vital to the exam, though only supported by “lowest strength of evidence.”1

As Flynn et al state,2 there may be more than one unique standard of care in a situation. The patient with an acute, symptomatic PVD should be diligently and thoroughly examined, and this examination traditionally includes indirect ophthalmoscopy often but not necessarily with scleral depression. There are few published reports in the literature on the topic of scleral depression for the detection of peripheral vitreoretinal pathology. These articles describe in detail the technique of scleral depression when used with indirect ophthalmoscopy, but they do not provide any objective comparison to alternative examination techniques, such as fundus examination without scleral depression.2-7

Our group studied 50 eyes of 25 patients without symptoms of flashes and floaters, and 50 eyes of 25 patients with symptoms of flashes and floaters. No statistically significant difference in peripheral vitreoretinal pathology was detected by the use of scleral depression in any of the 100 eyes of the total 50 patients enrolled in the study. Within the symptomatic group, 4 patients had peripheral retinal holes, 2 patients had sickle cell retinopathy (one active, one not), and 1 patient had a peripheral horseshoe tear. The remainder of pathology detected within this group was confined to the posterior pole and included posterior vitreous detachments, traction retinal detachments, and diabetic retinopathy. Based on our study, we found that a fundus exam using a 28D lens with scleral depression did not provide any additional benefit to an exam without depression during indirect ophthalmoscopy.8

In our study, patients reported a significantly higher level of discomfort with scleral depression than without (pain scale score of 4.68 with scleral depression vs 1.84 without). In our survey of practicing vitreoretinal specialists, we found that the majority of respondents do not use topical anesthesia prior to fundus exam with scleral depression (60%), suggesting that patient discomfort associated with scleral depression may be underappreciated amongst providers.8

In conclusion, “standard of care” is a legal term, not a medical term, and therefore it varies in different locations and settings and evolves over time.2 The standard of care does not mandate scleral depression in all patients or even just because a patient has retinal detachment “risk factors.”2 Undoubtedly, the use of scleral depression often adds another perspective to suspicious areas in the retina and may help clarify if a particular area is the cause of the associated symptoms and warrants further evaluation or treatment.

REFERENCES

- AAO Retina/Vitreous PPP Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Preferred practice pattern. Posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration. San Francisco, California: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at aao.org/ppp .

- Tran KD, Schwartz SG, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW. The role of scleral depression in modern clinical practice. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;195:xviii-xix.

- Townsend WD. Scleral depression. Optom Clin. 1992;2(3):127-144.

- Brockhurst RJ. Modern indirect ophthalmoscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41(2):265-272.

- Walters GB. The technique of scleral indentation. J Am Optom Assoc. 1982;53(7):569-573.

- Krausher MF. Learning scleral depression with binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87(1): 97-99.

- Schepens CL. Techniques of examination of the fundus periphery, in Symposium on retina and retinal surgery. Transactions of the New Orleans Academy of Ophthalmology. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1969;39-51.

- Shukla SY, Batra NN, Ittiara ST, Hariprasad SM. Reassessment of scleral depression in the clinical setting. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):2360-2361.

Comments from Pauline T. Merrill, MD

Uveitis section director at Rush University, vitreoretinal surgeon with Illinois Retina Associates, S.C., and OMIC committee member

For the first time in many years of practice, I recently met a patient whom I could not scleral depress. He was referred for a possible superior macula-on retinal detachment. As soon as I walked into the room, he apologized for being a “wimp” about his eyes. In reality, he had the strongest orbicularis oculi muscles I have ever encountered. So, as a staunch advocate of scleral depression, what did I do? First, as recommended in any patient with a “media opacity” (whether vitreous hemorrhage or squeezed-shut lids), I performed an ultrasound to look for any retinal tears. This confirmed superior retinal elevation in the both eyes, with no identifiable tears. I also obtained peripheral OCT scans, which fortunately confirmed the presence of superior retinoschisis with no subretinal fluid. Most importantly, I then discussed with the patient the fact that he could still have or develop a retinal tear or detachment, and the signs and symptoms to watch for. He expressed full understanding, and also suggested that he would take diazepam prior to his next visit. I documented all of this carefully in his chart.

Since meeting this patient, I am more sympathetic to colleagues who protest that scleral depression for every patient with flashes and floaters is too onerous, and not proven in the literature. Nonetheless, it is important for everyone to be familiar with the statement in the AAO PPP for posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration, updated in 2014: “The preferred method of evaluating patients for peripheral vitreoretinal pathology is by using an indirect ophthalmoscope combined with scleral depression. … Slit-lamp biomicroscopy with a mirrored contact lens … may complement a depressed indirect examination of the peripheral retina.” The Academy does make the disclaimer that the PPP “guidelines are not medical standards to be adhered to in all individual situations.”1

When possible, however, scleral depression is an excellent technique for identifying retinal tears, which may only become apparent with the unique dynamic movement of scleral indentation. In addition, even when you can’t visualize the ora for 360 degrees, simply taking the time to look with depression is likely to ensure a more thorough exam. With regard to patient discomfort, proper depression usually requires minimal force, and topical anesthetic can be utilized. The patient will remember, however, that you performed a careful and thorough exam.

As Dr. Colucciello notes above, the importance of identifying and treating retinal tears is underscored by a recent study by Dr. Anne Menke of OMIC. Dr. Menke looked at claims alleging diagnostic error over 7 years. Of these 223 claims, 65 (29%) involved retinal detachments.2 Factors contributing to diagnostic error included deficiencies in exams, documentation, and communication. Defense experts who reviewed the retinal detachment cases felt that documentation of scleral depression “would have significantly helped defend the care.”3 As Dr. Menke noted in an interview last year, it is important for the ophthalmologist to know the PPP recommendations, because the plaintiff’s attorney will. “Understanding and implementing these recommendations will protect your patient and may keep you out of court,” she said.4

The standard of care, or what a similarly trained practitioner would do under similar circumstances, depends on the details of each situation. Most retina specialists would agree that in a patient with flashes and floaters, the standard of care includes a full evaluation of the peripheral retina. As recommended by the AAO’s PPP, scleral depression is generally an ideal method to accomplish this. The findings of scleral depression, or the reason why it was not done, should be fully documented and communicated with the patient. Performing scleral depression will maximize your ability to identify retinal tears, will reassure the patient that you are doing your utmost to help them, and will help minimize your risk of medicolegal claims. RP

REFERENCES

- AAO Retina/Vitreous PPP Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Preferred practice pattern. Posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration. San Francisco, California: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at aao.org/ppp .

- Menke AM. Diagnostic error: types and causes. The OMIC Digest. 2016;26(1). Available at https://www.omic.com/diagnostic-error-types-and-causes/

- Menke AM. Failure to diagnose retinal detachments. The OMIC Digest. 2017;27(1):1,4,5,7. Available at https://www.omic.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Digest-No-1-10-10-17-entire-for-web-1.pdf

- Mott M. Malpractice risk: retinal detachment. Eyenet Magazine. 2018 April;49-53.