MELANOMA

UPDATE

Ocular

Oncology Essentials

Recognizing

and managing posterior uveal melanoma, pseudomelanomas and vascular tumors of the

retina and choroid.

During the 2006 Retinal Physician Symposium, (May 31-June 3, Atlantis, Paradise Island, Bahamas), Jerry A. Shields, MD, director of the Wills Eye Institute Oncology Service in Philadelphia, presented updates on the diagnosis and management of posterior uveal melanoma, pseudomelanomas of the posterior uvea and vascular tumors of the retina and choroid.

|

|

|

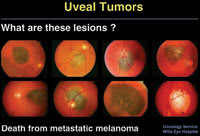

Figure 1. In each of these eight cases, the nevus or borderline lesion was observed for a short period of time and treated at the first evidence of growth. Each of the patients subsequently died of metastatic melanoma. |

POSTERIOR UVEAL MELANOMA

In his presentation on posterior uveal melanoma, Dr. Shields addressed the timing of treatment for small, presumed choroidal melanomas. In some cases, he said, observation can be risky (Figure 1). He cited select cases where small pigmented choroidal lesions were observed only and treated when growth was detected, and that subsequently metastasized and caused death.1 "This raises the intriguing question of whether we should treat choroidal nevi prophylactically," Dr. Shields said.

Arguments for treating all choroidal nevi exist, he said, namely: They are potentially malignant; small lesions can metastasize; and metastasis usually causes death. However, for several reasons, he does not recommend treating small asymptomatic nevi. First, they occur in only 5% of the population, so thousands of patients would be treated unnecessarily. Second, most small nevi have an excellent prognosis; growth and metastasis are rare overall. And third, treatment often causes vision loss.

Also, in a retrospective study of 1329 lesions <3 mm thick conducted by Carol Shields, MD, and colleagues,2 3% of the lesions metastasized (comparable to that seen in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study). In the study, four characteristics were statistically significantly related to eventual metastasis: thickness >2 mm at the initial visit; presence of symptoms from the lesion; proximity to the optic disc; and documented growth. "Docu-mented growth proved to be a very significant factor in this study for metastatic disease," Dr. Shields said. "If none of these risk factors is present, the chances of meta-stasis are <1%. If one factor is present, the likelihood is 5%; two factors, 10%; three factors, 15%; and if you wait for all four factors to be present, including growth, the risk of metastasis is higher than 20%." Dr. Shields advises patients about treatment based on these percentages.

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Classic peripheral disciform hemorrhages (peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy) simulating a melanoma. | |||

He and other physicians in his practice also take into account the mnemonic TFSOM (to find small ocular melanomas) proposed by Dr. Carol Shields when deciding the best management for small presumed choroidal melanomas — thickness >2mm, fluid (subretinal), symptoms, orange pigment and margin closer than 3 mm to the optic disc. "If the patient has three or more of the TFSOM risk factors, the chance of nevus growth and progression to melanoma is 50%," Dr. Shields said.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

When the decision is made to treat a small, presumed choroidal melanoma, several therapies are available. "The most common way of treating uveal melanomas today is with plaque radiotherapy," Dr. Shields said. "We generally see a nice regression of the tumors after therapy, which is interpreted as a good result, but may not necessarily portend a better prognosis."

Dr. Shields said plaque radiotherapy can be used to treat juxtapapillary, subfoveal, ciliary body and iris melanomas as well as melanomas with extraocular extension. "Concerning juxtapapillary melanoma, plaque radiotherapy can induce some optic atrophy," he said. A study of juxtapapillary melanomas by Dr. Shields and colleagues found patients' survival rates to be equal whether plaque treatment or enucleation was used.3 The study also showed a trend toward a better survival rate in patients older than 50 when plaque rather than enucleation was used.

Dr. Shields and colleagues have performed plaque radiotherapy and achieved favorable results for large melanomas in patients who have refused enucleation. However, he said, "most of these patients eventually have more severe complications, and 20% come to enucleation within 5 years."

|

|

|

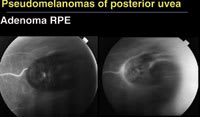

Figure 3. Adenomas of the retinal pigment epithelium appear black and pedunculated, but fluorescein angiography typically shows a feeder vessel, which would not be seen with a melanoma. |

Transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT), despite some criticisms about complications, is also an effective treatment, Dr. Shields said, citing a large case series he and colleagues reported.4 For example, they used TTT to treat a patient with a 3-mm thick melanoma above the disc, an impending break through Bruch's membrane, subretinal fluid and 20/40 vision. "Seven years later, the tumor is completely eradicated," Dr. Shields said. "The subretinal fluid resolved. The patient has 20/20 vision and is flying commercial airplanes. If we had treated that same lesion with proton beam or plaque, the patient would not have had such a good outcome."

Local resection is another treatment option for uveal melanoma. "We do this for selected ciliary body and peripheral choroidal melanomas that are localized with a small base," Dr. Shields said. "We try to leave the retina intact in these cases."

Combination therapies, such as plaque radiotherapy and thermotherapy, plaque and resection, and external radiation and enucleation, are used frequently in Dr. Shields' practice. "We often recommend enucleation because we feel morbidity from radiotherapy is so great for patients with certain large tumors that overhang the disc that enucleation is best," he said. "Also, if a larger melanoma is more than 8 mm to 10 mm thick, we generally lean more toward enucleation."

Primary orbital exenteration for uveal melanoma may be necessary for massive orbital extension of the tumor. "We perform the lid-sparing exenteration, removing the orbital contents and suturing the lids together. They heal rapidly, and the patient can be fitted with a prosthesis in 5 or 6 weeks."

MELANOMA PROGNOSIS

|

|

| Figure 4. This uveal prolapse following otherwise successful cataract surgery was first thought to be an extraocular extension of a ciliary body melanoma. |

Turning to the prognosis for melanoma, Dr. Shields talked about genetic abnormalities, particularly those linked to chromosome 3. "Patients with uveal melanoma have been found to have either a monosomy pattern associated with a much higher 5-year death rate or a disomy pattern associated with a much lower 5-year death rate," he said. Dr. Carol Shields is spearheading a study in which tumor tissue is being obtained for genetic studies. This tissue is being obtained by opening the globe after enucleation or by fine-needle aspiration technique in patients receiving a radioactive plaque. Patients with the chromosome 3 monosomy are assigned to a more rigid follow-up protocol, including interferon therapy. Patients with the disomy pattern undergo standard screening for metastatic melanoma.

PSEUDOMELANOMAS OF THE POSTERIOR UVEA

Dr. Shields also discussed pseudomelanomas of the posterior uvea. He described a review of 12,000 consecutive cases that were referred to the Wills Eye Institute Oncology Service for the purpose of confirming or ruling out melanoma. Among those cases, 1739 (14%) were actually pseudomelanomas. He described the ophthalmoscopic features of several of the 54 conditions that were determined to be pseudomelanomas.

■ Choroidal nevus. This condition was the most commonly mistaken for melanoma among the 12,000 cases (49% of the pseudomelanomas). While nevi can be slightly elevated, they are rarely more than 2 mm thick. Although most have some pigment, others are entirely amelanotic. In such cases, close examination often reveals a small amount of inherent pigment, suggesting it is a melanocytic lesion, rather than a metastasis or granuloma.

■ Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), or peripheral disciform lesion. PEHCRs produce much more exudation and hemorrhage, sometimes massive, than a comparable size melanoma (Figure 2).

■ Congenital hyperplasia of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) CHRPEs have a black appearance, a depigmented halo, and depigmented lacunae through which choroidal vessels can be seen.

■ Hemorrhagic detachment of the RPE. Some of these contain a layering of blood within the cavity, which would not be seen with a melanoma. "We often see these with turbid pigment epithelial detachments," Dr. Shields explained.

■ Choroidal hemangioma. The typical orange color differentiates these from most melanomas. Fluorescein, indocyanine green and ultrasound are helpful in the differential diagnosis.

|

|

|

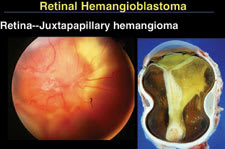

Figure 5. Juxtapapillary hemangioblastomas tend to be much more aggressive in young patients, particularly those who have von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. This eye with a hemangioblastoma on the optic disc was eventually enucleated after failed retinal detachment surgery. |

■ Hemorrhage due to age-related macular degeneration. Dr. Shields and associates see several patients per year with a disciform hemorrhage in the macular region, and compared with a similar size melanoma, these lesions exhibit much more hemorrhage and blood in various stages of resolution.

■ Metastasis. Metastasis can be similar to amelanotic melanoma but is usually amelanotic and has a homogeneous, creamy-yellow color. In the Wills Eye review of 1739 pseudomelanomas, 34 cases (2%) of metastasis were referred with the diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma. During that time, more than 1000 patients with uveal metastasis were seen on the Oncology Service.

■ Vasoproliferative tumor. These tumors produce an elevated mass, but they produce more hemorrhage and exudation than a melanoma, and they have feeder vessels from the sensory retina.

■ Adenoma of the RPE. While these tumors are dark, black and pedunculated, with time they produce a dilated feeding artery and draining vein and Coats-like exudation (Figure 3). "This would not be seen with a melanoma but is very typical of pigment epithelial tumors," Dr. Shields said.

■ Sclerochoroidal calcification. Characteristics include a yellow-orange geographic mass, often along the superior arcades. The calcifications are often bilateral and associated with certain congenital renal diseases, such as Bartter Syndrome and Gitelman Syndrome.

■ Adenoma of the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium. These tumors can be fleshy and have a white-gray appearance. Resection by iridocyclectomy, taking out the tumor with a wide margin, is often an effective treatment.

■ Vortex vein varix. A vortex vein varix, which can grow to tumorous proportions, can appear to be a melanoma because it is a dark, elevated mass. "This may not be visible if you have the patient look in another direction, or if you gently compress the globe," Dr. Shields said.

|

|

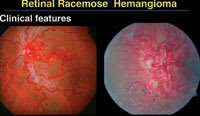

| Figure 6. A racemose hemangioma can be very complex, creating a snake-like red growth throughout the entire fundus. |

■ Choroidal hemorrhage. A choroidal hemorrhage can simulate melanoma, but it is usually hypofluorescent on angiography. "It can occur after cataract surgery, even when the surgery is uncomplicated," Dr. Shields said, "so you have to consider [choroidal hemorrhages] if you see what looks like a melanoma after cataract surgery."

The final pseudomelanoma that Dr. Shields discussed was a case of uveal prolapse following otherwise successful cataract surgery (Figure 4). The referring doctor had suspected extraocular extension of a ciliary body melanoma. Transillumination rules out melanoma in this case, he said, because the uvea would transmit light.

VASCULAR TUMORS OF THE RETINA AND CHOROID

When diagnosing vascular retinal tumors, it is important to be specific, Dr. Shields said. He advised physicians to go beyond the diagnosis of "retinal hemangioma" and classify tumors as hemangioblastoma, cavernous hemangioma, racemose hemangioma or vasoproliferative tumor because each type has its own clinical significance, systemic associations and treatment. "Hemangioblastoma is a more appropriate term that I hope retinal specialists will begin to adopt, rather than retinal capillary hemangioma, in keeping with the neurosurgical and neuropathology literature," he said.

|

Cases from the Wills Eye Institute Oncology Service |

|

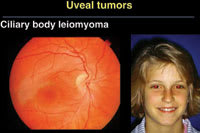

As part of his presentations on ocular oncology

at the 2006 Retinal Physician Symposium, Jerry A. Shields, MD, director of the Wills

Eye Institute Oncology Service in Philadelphia, highlighted a case of an intraocular

leiomyoma that simulated a uveal melanoma (Figures A and B). |

HEMANGIOBLASTOMA

A retinal hemangioblastoma often assumes a dilated retinal feeding artery, draining vein and yellow exudation. It can be located over the optic disc, where it has the same clinical significance as a tumor in the periphery and also can be associated with von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. Hemangioblastomas can be classified as one of two types, exudative or tractional. The exudative type is a red-yellow lesion with a large amount of exudation and subretinal fluid but no significant vitreous traction. The tractional type develops vitreous condensation, haze and a pulling on the retinal vessels. Sometimes, both conditions occur together.

The management of retinal hemangioblastoma can be observation if it is a small, localized lesion without von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. Active treatment options are laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy and sometimes, vitrectomy and endolaser if there is vitreous traction. Dr. Shields explained how to treat small hemangioblastomas with laser photocoagulation. "Mainly, close the feeding retinal artery," he said. "Also treat around it; otherwise, some of the small vessels that are present will take over and become the feeding artery. During a second session, begin to treat the vein. We treat the artery first because treating the vein first might cause backup and vitreous hemorrhage."

Juxtapapillary hemangioblastomas are the most difficult to treat, Dr. Shields said (Figure 5). They tend to be much more aggressive in young patients, particularly those who have von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome.

CAVERNOUS HEMANGIOMA

"Cavernous hemangiomas are really quite different," Dr. Shields continued. They have been described as resembling a cluster of grapes in the retina. They are usually located along the epicenter of a vein, and they do not have a feeder artery. They do not produce exudation, but may have white fibroglial tissue near their surface. Complications can include vitreoretinal traction, tractional retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage.

The hereditary pattern for this condition is known. "It is an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with low penetrance," Dr. Shields said. "An unusual change has been identified in chromosome 17 and the KRIT 1 gene."

Retinal cavernous hemangiomas are generally managed by observation. According to Dr. Shields, they are relatively asymptomatic or present with some foveal traction that may be difficult to treat. Laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy can be used when the tumor causes recurrent vitreous hemorrhage. For tumors creating dense vitreous hemorrhage, vitrectomy and endolaser can be used.

RACEMOSE HEMANGIOMA

Racemose hemangioma is associated with midbrain lesions in Wyburn-Mason Syndrome, for which no genetic abnormalities have been recognized. "A race-mose hemangioma can create a dramatic retinal picture of arteriovenous communication," Dr. Shields said (Figure 6). Similar findings can be present in the central nervous system and on the skin as part of a neurooculocutaneous syndrome.

Management of racemose hemangiomas is generally observation. "On rare occasions, we have seen them cause a branch retinal vein obstruction or significant vitreous hemorrhage," Dr. Shields said. "The hemorrhage generally resolves without treatment."

RETINAL VASOPROLIFERATIVE TUMOR

Dr. Shields described the two types of vasoproliferative tumors, primary and secondary. The primary type usually occurs at the equator, most often inferotemporally, as a dome-shaped waxy mass. It develops retinal feeder vessels, which are not as dilated and torturous as those seen with hemangioblastoma. It often produces extensive hemorrhage and exudation. "Unlike the hemangioblastoma, where one sees circinate or stellate exudates in the fovea, remote from the lesion, the exudate from these primary vasoproliferative tumors tends to creep back toward the fovea as a wall, which is a different pattern of progression," Dr. Shields explained.

The secondary type can occur following a variety of ocular insults. "We see it most often with pars planitis and retinitis pigmentosa," Dr. Shields said. It has also been seen with toxocariasis, Coats disease, chronic retinal detachment of any cause and dominant exudative vitreoretinopathy.

| Choroidal Hemangioma |

|

Dr. Shields also addressed choroidal hemangioma, which occurs in two types, diffuse and circumscribed. The diffuse type is associated with facial nevus flammeus and variations of Sturge-Weber Syndrome. The circumscribed type is seen more often by retinal specialists. In general, it is unilateral, nonfamilial and characterized by a red-orange mass in the posterior fundus, almost never anterior to the equator. Circumscribed choroidal hemangioma often produces a secondary retinal detachment in young or middle-age patients. "Lesions of this type can be managed with observation when they are asymptomatic, but laser photocoagulation and radiotherapy using proton beam or plaques have been highly successful treatments," Dr. Shields said. "Use of thermotherapy has been reported, and photodynamic therapy has recently gained popularity." |

The management of vasoproliferative tumors is complex, Dr. Shields said. This type of lesion with exudation should prompt a lipid profile study because some are associated with hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia. Often, small tumors in the periphery are only observed, but laser photocoagulation can be used, as can cryotherapy for larger tumors. "We have had considerable experience with radioactive plaques for the larger ones that are more difficult to treat," Dr. Shields said. "And photodynamic therapy has been used in some patients."

REFERENCES

1. Eskelin S, Pyrhonen S, Summanen P, et al.Tumor doubling times in metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea: tumor progression before and after treatment. Ophthalmol. 2000;107:1443-1449.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Kiratli H, et al. Risk factors for metastasis of small choroidal melanocytic lesions. Ophthalmol. 1995;102:1351-1361.

3. DePotter P, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Enucleation versus plaque radiotherapy in the management of juxtapapillary choroidal melanoma. Brit J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:109-114.

4. Shields CL, Shields JA, Perez N, et al. Primary transpupillary thermotherapy for choroidal melanoma in 256 consecutive cases. Outcomes and limitations. Ophthalmol. 2002;109:225-234.