Improvements in the Detection and Management

of Choroidal Melanoma

CAROL

L. SHIELDS, MD • JERRY A. SHIELDS, MD

There have been several new developments in the management of patients with choroidal melanoma over the past decade. Depending on the clinical circumstances, observation, photocoagulation, transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT), plaque radiotherapy, charged particle irradiation, local resection, enucleation, orbital exenteration, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy have been employed.1-19 There has been a trend away from photocoagulation, with increasing interest in TTT alone for small melanomas or TTT in combination with radiotherapy for small, medium, and some large melanomas. The recently recognized clinical risk factors for growth and metastasis of small melanocytic tumors allows for earlier detection and treatment of small choroidal melanoma. Consequently, there is a trend away from observation and a focus toward earlier treatment of small melanocytic lesions that possess risk factors.

Historically, enucleation of the affected eye was once considered to be the only appropriate management for the patient with a uveal melanoma. Several years ago some authorities challenged the effectiveness of enucleation for preventing metastatic disease and even proposed that enucleation may somehow promote or accelerate metastasis. This was known as the Zimmerman hypothesis. The validity of these arguments was challenged by others, who believed that early enucleation offered the patient the best chance of cure. This controversy over enucleation was responsible for initiating a trend away from enucleation towards more conservative therapeutic methods.

Depending upon several clinical factors, management options today include observation, TTT, radiotherapy, local resection, enucleation, and various combinations of these methods. The 2 most frequently employed treatment methods today are enucleation and plaque radiotherapy. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) was organized and funded in 1985 to address several issues related to the management of choroidal melanoma.3-5 More recently, there has been a trend towards detection of smaller choroidal melanomas and increasing use of conservative treatment methods like plaque radiotherapy.6,7

HOW CAN WE JUDGE IF A CHOROIDAL NEVUS WILL EVOLVE INTO MELANOMA?

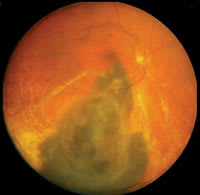

Approximately 6% of the Caucasian population manifest a choroidal nevus.8 Choroidal nevi are managed by periodic observation. It is estimated that 1 in 5000 choroidal nevi will evolve into choroidal melanoma. Risk factors predictive of growth of small melanocytic lesions into melanoma are listed in Table 1 (Figure 1).

WHAT IS TTT AND HOW WELL DOES IT WORK?

Transpupillary thermotherapy is a recently popularized method of treating selected small choroidal melanomas. With this technique, infrared radiation, using a modified diode laser system, delivers heat to the tumor, causing tumor necrosis. Transpupillary thermotherapy is typically delivered in 3 sessions and, at completion, leaves an atrophic chorioretinal scar at the site of the previous tumor. Tumor control is found in over 90% of properly selected cases.9 The tumors most suitable for TTT are small, heavily pigmented, less than 3 mm in thickness, with minimal or no suberetinal fluid, and located in the extramacular region, not touching the optic disc. Tumors at the optic disc show greater recurrence and are best managed with plaque radiotherapy combined with TTT.

WHAT IS THE LOCAL SUCCESS RATE OF PLAQUE RADIOTHERAPY AND CHARGED PARTICLE RADIOTHERAPY?

|

| Figure 1. Small choroidal melanoma with 4 risk factors for growth including symptoms of photopsia, shallow subretinal fluid, overlying orange pigment, and tumor margin near the disc. |

Radiotherapy is still the most widely employed treatment for posterior uveal melanoma. The most commonly employed form of radiotherapy is brachytherapy, using a radioactive plaque. Radioactive isotopes for plaque radiotherapy include Iodine-125 and Ruthenium-106 and these have replaced Cobalt-60 at most institutions. Plaque radiotherapy can be used for small, medium, and even large melanomas (Figure 2).10,11 Plaque radiotherapy can be custom designed for treatment juxtapapillary melanoma using a notched plaque, ciliary body melanoma using a round or curvilinear plaque, iris melanoma using a curvilinear plaque, and even extrascleral extension of uveal melanoma.

Another method of radiotherapy is charged particle irradiation.12-14 This technique provides a focused beam of radiotherapy to the region of the tumor from an external source. Local tumor control following plaque radiotherapy and charged particle radiotherapy is similar at 97%. All patients treated with plaque or charged particle radiotherapy should be monitored for tumor control and visual acuity loss. The main cause of visual loss is radiation maculopathy, papillopathy, cataract, and secondary glaucoma.

WHAT WERE THE MAIN RESULTS OF THE COMS?

The COMS was designed to evaluate management of choroidal melanoma in a prospective fashion. The COMS included 2 major studies including: the large choroidal melanoma trial comparing enucleation vs. enucleation preceded by external beam radiotherapy and the medium choroidal melanoma trial comparing enucleation vs. plaque radiotherapy. The results of the large tumor trial showed no difference in patient survival between enucleation and pre-enucleation radiation groups.3 Five year Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival was 57% for the enucleation group and 62% for the pre-enucleation radiation group. The medium tumor trial showed no difference in patient survival between enucleation and plaque radiotherapy.4 Five year Kaplan-Meier estimates for histopathologically-confirmed melanoma metastasis were 11% in the enucleation group and 9% in the plaque radiotherapy group.

WHAT ROLE DOES LOCAL RESECTION PLAY IN THE MANAGEMENT OF UVEAL MELANOMA?

Local resection is reserved for small to medium melanomas involving

the iris, ciliary body, and anterior choroid using a partial lamellar sclerouvectomy

technique.16 This technique

involves microsurgically dissecting a scleral flap over a tumor to allow safe removal

of the tumor intact with tumor free margins on the base (normal sclera), at the

margin (normal choroid), and at the apex (normal retinal pigment epithelium). Local

resection is designed to immediately remove the tumor with preservation of vision

without cosmetic deformity of the eye. If the tumor proves to have epithelioid melanoma

cells or tumor close to the margin, the surgical wound is treated with a dose of

plaque radiotherapy. Potential complications of resection include vitreous hemorrhage,

retinal detachment and cataract. Patient survival following local resection is

similar to enucleation and radiotherapy.

DO WE STILL ENUCLEATE EYES WITH MELANOMA?

Enucleation is indicated for advanced melanomas that occupy 40% or more of the intraocular structures and for those that have produced secondary glaucoma (Figure 3). Another relative indication for enucleation is melanoma with optic nerve invasion. However, many juxtapapillary melanomas that abut the optic nerve and show no evidence of invasion can be managed by a custom-designed notched radioactive plaque rather than enucleation. The enucleation technique for intraocular tumors involve a gentle surgical approach of identification, tagging, and detachment of the 4 rectus muscles and detachment of the 2 oblique muscles. A long section of optic nerve should be achieved without clamping prior to cutting it. There have been advances in the types of orbital implants used following enucleation. The hydroxyapatite and polyethylene (Medpor) implants are the 2 most popular motility implants whereby motility is achieved by attaching the 4 rectus muscles to their anatomic location on the implant.

|

|

| Figure 2. Plaque

radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma. Top: Before treatment, the large choroidal melanoma and extensive retinal detachment is noted. Bottom: Following plaque radiotherapy (10 months later), the tumor has regressed and the subretinal fluid has resolved. |

ARE THERE ANY EFFECTIVE SYSTEMIC THERAPIES FOR METASTATIC MELANOMA?

Ideally, the best management of uveal melanoma would be to use methods of preventing metastasis in the early stages of the intraocular disease. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that chemotherapy or immunotherapy is effective in the primary management of uveal melanomas. Options for improving life prognosis without cure for patients with systemic metastases include immune therapy using vaccines or immune-boosting medications such as interferon or granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor (GMCSF), chemotherapy, chemoembolization, immune embolization, or local resection.17,18

WHAT ARE FUTURE DIRECTIVES FOR MANAGEMENT OF UVEAL MELANOMA?

Some chromosomal abnormalities have been identified in uveal melanoma on chromosome3, 6, 8, 9,19 Monosomy of chromosome 3 imparts a particularly worse prognosis and such patients are followed for metastatic disease more aggressively. High risk patients are considered for inclusion in clinical trials for prevention of metastasis.

REFERENCES

1. Shields JA, Shields CL..The management of posterior uveal melanoma In Shields JA, Shields CL, eds. Intraocular Tumors. A Text and Atlas. Philadelphia. Pa: Saunders; 1992:191-192.

2. Shields JA, Shields CL. The management of posterior uveal melanoma. In Shields JA, Shields CL, eds. Atlas of Intraocular Tumors. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:113-140.

3. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The collaborative ocularmelanoma study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma II: initial mortality findings. COMS report no. 10. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126: 779-796.

4. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The COMS randomized trial of Iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma, III: Initial mortality findings. COMS report no. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119: 969-982.

5. Benson WE. The COMS: Why was it not stopped sooner? Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:672.

6. Shields CL Shields JA, Kiratli H, Cater JR, De Potter P. Risk factors for growth and metastasis of small choroidal melanocytic lesions. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1351-1361.

7. Shields CL, Cater JC, Shields JA, Singh AD, Santos MCM, Carvalho C. Combination of clinical factors predictive of growth of small choroidal melanocytic tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118: 360-364.

8. Sumich P, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Choroidal nevi in a white population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:645-650.

9. Shields CL, Shields JA, Perez N, Singh AD, Cater J. Primary transpupillary thermotherapy for small choroidal melanoma in 256 consecutive cases: outcomes and limitations. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:225-234.

10. Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA, et al. Combined plaque radiotherapy and transpupillary thermotherapy for choroidal melanoma in 270 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:933-940.

11. Shields CL, Naseripour M, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for large posterior uveal melanoma (>8 mm in thickness) in 354 consecutive patients. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1838-1849.

12. Gragoudas ES, Goitein M, Verhey L, Munzenreider J, Suite HD, Koehler A Proton beam irradiation. An alternative to enucleation for intraocular melanomas. Ophthalmology. 89:571-581, 1980.

|

| Figure 3. Enucleation for large choroidal melanoma. |

13. Seddon JM, Gragoudas ES, Albert DM, Hseih CC, Polivogianis L, Fridenberg GR: Comparison of survival rates for patients with uveal melanoma after treatment with proton beam irradiation or enucleation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:282-290.

14. Char DH, Kroll SM, Castro JK. Ten-year follow-up of Helium ion therapy of uveal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:81-89.

15. Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma. Long-term visual outcome in 1106 patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1219-1228.

16. Shields JA, Shields CL, Shah P, Sivalingam V. Partial lamellar sclerouvectomy for ciliary body and choroidal tumors. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:971-983.

17. Aoyama T, Mastrangelo MJ, Berd D, et al. Protracted survival following resection of metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1561-1568.

18. Mavligit GM, Charnsangevej C, Carrasco H, et al. Regression of ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver after hepatic arterial chemoembolization with cisplatin and polyvinyl sponge. JAMA.1988;260:974-976.

19. Shields JA. Future management of posterior uveal melanoma. Editorial. Ophthalmic Practice. 2001;19;4.

Jerry Shields, MD, is director, oncology services at Wills Eye Hospital and professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University. Carol Shields, MD, is co-director, oncology services at Wills Eye Hospital and professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University. Support provided by the Macula Foundation, New York, NY and the Eye Tumor Research Foundation, Philadelphia, PA. Neither author has any financial interest in the information contained in this article.