PEER REVIEWED

Uveitis: Clinical Assessment and Treatment

GRACE A. LEVY-CLARKE, MD, LEILA I. KUMP, MD and ROBERT B. NUSSENBLATT, MD

A careful and detailed medical history combined with a comprehensive review of systems is one of the keys to correctly identifying the underlying etiology in patients with uveitis. In the clinical assessment one can simplify the process if a 3-tier approach is utilized. First obtain the medical history with a comprehensive review of systems, second do the clinical examination, and third formulate a working differential diagnosis. After this is accomplished, a therapeutic paradigm can be developed.

The detailed medical history should include documentation of the patient's age, sex, race, ethnicity, and occupation. Family, social, sexual, and surgical history should also be disclosed. A detailed past ocular history should include the history of the present illness, with documentation of onset, duration, course, inciting agents, surgical intervention, as well as previous therapy and response in chronological order.

We will not discuss anterior uveitis in this article.

CLASSIFICATION SCHEMA

After a detailed medical history and ophthalmic examination, an attempt should be made to classify the uveitis, to begin the process of developing a working differential diagnosis. We recommend a classification schema based on duration, characteristics, laterality, location, demographics, associated signs, and therapeutic response:

Duration. For disease duration, a distinction should be made between acute and chronic disease. Acute being disease that is sudden in onset with a duration of 6 weeks or less. Chronic should include disease that is insidious in onset and persisting for >6 weeks. Common causes of acute uveitis are most anterior uveitis, toxoplasmosis, white-dot syndromes, acute retinal necrosis (ARN), and trauma. Common causes of chronic uveitis are juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis, birdshot choroidopathy, serpiginous choroidopathy, tuberculous uveitis, intraocular lymphoma, sympathetic ophthalmia, multifocal choroiditis, sarcoid uveitis, intermediate uveitis, and pars planitis.

Characteristics. The inflammation can be classified based on the type of inflammatory cells that are noted on clinical examination. Fine, white-colored keratic precipitates (KPs) characterize nongranulomatous inflammation. Large, greasy appearing KPs ("mutton fat" KPs), iris nodules, or choroidal granulomas usually characterize granulomatous inflammation. Importantly, the finding of granulomatous inflammation is usually suggestive of a unique set of etiologic agents. Causes of granulomatous uveitis are sarcoidosis, sympathetic ophthalmia, uveitis associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), lens-induced uveitis, intraocular foreign body, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, syphilis, tuberculosis, or other infectious agents.

Laterality. Most types of uveitis tend to become bilateral, as it evolves over weeks to months, even though the initial presentation may be unilateral. Therefore, the history that the disease remains unilateral can be an important diagnostic clue. Causes of unilateral uveitis are sarcoidosis, postsurgical uveitis, intraocular foreign body, parasitic disease, ARN, and Behçet's disease.

Anatomic location. The anatomic classification of uveitis that we utilize, is the classification proposed by the International Uveitis Study Group. Anterior uveitis is inflammation primarily involving the iris and ciliary body. Intermediate uveitis is inflammation primarily involving the vitreous, pars plana, and the peripheral retina. Posterior uveitis is inflammation involving the retina and choroid. Panuveitis is inflammation involving the entire uveal tract and adjacent structures. The common causes of uveitis are in the Table.

Demographics. The following demographic features will be helpful in the assessment of patients with intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis:

► Race and Ethnicity:

- Sarcoidosis epidemiologic studies indicate that in the United States, the age-adjusted annual incidence of sarcoidosis in African-Americans is 82 per 100 000 and in Caucasians it is 8 per 100 000

- VKH a high percentage of cases reviewed by the National Eye Institute (NEI) were of American-Indian heritage

- VKH this is a common type of endogenous uveitis in Japan

► Gender:

- VKH 79% of the cases reviewed by the NEI were females

- Behçet's disease a review of the patients at the NEI revealed a male propensity.

► Geographic location:

- Lyme disease should be taken into consideration with patients who give a history of hiking in wooded areas, mostly in Northeast (MA to MD), Midwest (WI and MN), and West Coast (CA and OR).

► Lifestyle:

- Sexual promiscuity should alert physicians to consider syphilis and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related ocular complications

- Intravenous drug abuse should raise suspicion for fungal endophthalmitis and AIDS

Associated signs. The 2 types of associated signs of uveitis are ocular and systemic.

► The ocular signs are:

- Type of KPs: "mutton fat" KP with granulomatous disease

- Presence of hypopyon: Behçet's disease, endophthalmitis, sarcoidosis

- Iris atrophy: herpetic disease

- Iris nodules: granulomatous disease

- Dalen-Fuchs nodules (peripheral, small, discrete, deep, yellow-white chorioretinal lesions): sarcoidosis, sympathetic ophthalmia

- Papillitis: VKH, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, MS, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis

- Secondary glaucoma: herpetic disease

- Retinal granuloma: toxocariasis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, syphilis.

► The systemic signs are:

- Nyctalopia with posterior uveitis: birdshot retinochoroidopathy

- Vertigo or dysacusis: VKH, MS

- Diarrhea: inflammatory bowel disease or Whipple's disease

- Headaches and neurologic complaints: VKH, Behçet's disease, polyarteritis nodosa, central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, cryptococcosis, Lyme disease, or herpes uveitis

- Oral or genital ulcers: Behçet's disease, Reiter's syndrome (anterior uveitis)

- Skin rashes: lupus, Lyme disease, Behçet's disease, sarcoidosis, or onchocerciasis.

Therapeutic response. Infectious uveitis may initially be responsive to anti-inflammatory therapy, but can later worsen, such as postsurgical endophthalmitis caused by propionibacterium acnes. Masquerade syndromes are syndromes that simulate chronic inflammatory disorders. They may be malignant or nonmalignant. These disorders typically are chronic, and medically unresponsive to therapy, or promptly recur when therapy is discontinued. The most common malignant masquerade syndrome is intraocular lymphoma. While intraocular foreign body is a common nonmalignant masquerade to rule out.

|

Table. Common Causes of Uveitis |

||

| Intermediate Uveitis | Panuveitis | Posterior Uveitis |

| Sarcoidosis | Syphilis | Taxoplasmosis |

| Inflammatory bowel syndrome | Sarcoidosis | Herpetic virus |

| Multiple sclerosis | Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) | Sarcoidosis |

| Lyme disease | Infectious endophthalmitis | Taxocariasis |

| Pars planitis* | Behçet's disease | Histoplasmosis |

| * Intermediate uveitis with no known etiology, this subtype tends to have a worse prognosis. | ||

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH AND MANAGEMENT OF INTERMEDIATE UVEITIS

The International Uveitis Study Group has defined intermediate uveitis as an inflammatory syndrome, affecting anterior vitreous, peripheral retina, and ciliary body with minimal or no involvement of the anterior segment or choroid. There can also be an associated peripheral perivasculitis.

Intermediate uveitis1-7 is estimated to represent 8%22% of all uveitis patients and one fifth of all cases of pediatric uveitis. Most cases are bilateral; however, about one third of patients may initially have only unilateral involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Patients generally present with complaints of floaters and blurred vision. Vitreous cells and haze are the most important finding in patients with intermediate uveitis. Vitreous "snowballs" may be seen in the inferior vitreous, and represent aggregates of inflammatory cells. Cellular exudates on the pars plana may be seen on a depressed, peripheral-retinal examination. The accumulation of old cellular debris and crenated residua of prior vitreal exudates may form a band along the pars plana and ora serrata. This has been termed "snowbanks." The extent of the "snowbanks" may vary from a few clock hours, mostly inferiorly, to 360š of the retinal periphery. The term pars planitis is also used to describe the subset of patients with intermediate uveitis with "snowbank". The presence of "snowbanks" is associated with worse visual prognosis.

Patients typically have a "quiet" and white eye. Pain, redness, tearing, and photophobia are less common and present when there is an accompanying anterior uveitis, which is seen more commonly in children with pars planitis than in adults. Children presenting with idiopathic pars planitis have a worse visual acuity both at initial diagnosis and at follow-up than do adults.

Common sequelae of intermediate uveitis include cystoid macular edema, cataract, glaucoma, retinal neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, as well as tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. In patients with pediatric onset, the associated anterior uveitis may result in band keratopathy.

Diagnosis

Clinical investigation should start with careful history taking, and a review of systems in conjunction with the examination.

Neurologic signs and symptoms may be associated with MS. The diagnosis of pars planitis may precede the diagnosis of MS, found concurrently or in later years. These patients are usually white females with bilateral intermediate uveitis/pars planitis. The reported incidence of uveitis in MS varies in different studies from 1%33%. Neurology consultation with brain magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) would be indicated. One should also consider HLA-typing; there is an association between intermediate uveitis, MS, and positive HLA-DR2 haplotype.

Exposure to ticks, the presence or history of a rash, or arthritis may suggest a possibility of Lyme disease. Serologic testing can be done to aid in the clinical diagnosis. A history of chronic or bloody diarrhea, or abdominal cramping should alert the clinician to inflammatory bowel disease. In addition to treating the ocular disease, early treatment for the gastrointestinal complications, which can occur is also critical to the patient's care.

It is important to exclude infectious causes of intermediate uveitis if the suspicion arises. If serologic tests for Lyme disease are negative, then other infectious entities should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting, such as Whipple's disease, human T-cell leukemia virus type1 (HTLV-1), West Nile virus, peripheral toxocariasis (unilateral intermediate uveitis in childhood), syphilis, and tuberculosis.

Treatment

Although intermediate uveitis is often considered one of the most benign forms of uveitis, accurate statistics about the overall prognosis of patients with this disease are not available. The severity of intermediate uveitis that occurs in the chronic phase of inflammation does lead to significant visual impairment.

Stepladder Approach

We use a stepladder approach for treatment of intermediate uveitis; after treatable infectious or malignant entities are excluded, we use the following algorithm for treatment of intermediate uveitis.

The first step is administration of regional corticosteroid injections (triamcinolone, 40 mg). Periocular injections may be safely performed in the office in children as young as 10 years of age with good cooperation. This is deemed a failure if the inflammation is still uncontrolled after 2 or 3 injections given over 69 weeks.

Step 2 is a short course of systemic corticosteroids for persisting inflammation in spite of periocular therapy. Prednisone is prescribed at a dose of 0.51.0 mg/kg/d PO, with the initiation of tapering guided by clinical response. We limit the oral steroid therapy to no more than 3 months of a tapering regimen.

Step 3 is immunosuppressive chemotherapy (corticosteroid sparing agents), including cyclosporine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil as a first choice. Azathioprine is used as a second choice, and cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil are used a last resort.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH AND TREATMENT OF POSTERIOR UVEITIS

Posterior uveitis1-3, 8-19 is a common form of uveitis. Frequently it is associated with an infectious or systemic underlying etiology.

SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder that can affect almost every organ in the body. The organs most commonly involved are the lungs, thoracic lymph nodes, and skin.

Clinical Manifestations

Ocular Manifestations

Many patients are asymptomatic at the time of their presentation and are diagnosed after an abnormal chest x-ray or laboratory test. Some patients with sarcoidosis may present with respiratory symptoms; however, some patients may have generalized symptoms such as fever, fatigue, or weight loss.

Ocular disease is usually bilateral, but may be asymmetrical or unilateral. Ophthalmic involvement includes 25%50% of patients. In up to 17% of patients palpebral conjunctiva contains sarcoid granulomas and lacrimal gland involvement is present in 26% of patients.

Posterior Pole Involvement

Inflammation of the vitreous, retina, and choroid is more visually disabling and occurs in up to 33% of patients. "Snowballs" (candle wax drippings) along the retinal veins can be seen, as well as perivenous sheathing. Periarterial sheathing is rare. Small areas of peripheral venous occlusion may be observed. Dalen-Fuchs nodules, yellow choroidal lesions, and mottling of retinal pigment epithelium occur in 36% of patients. Choroidal granulomas may also develop. They are hypofluorescent in the early stage of an angiogram, and hyperfluorescent in the late stage. Optic nerve involvement includes granuloma (with or without disc edema), papillitis (secondary to the posterior uveitis), and unspecified hyperemia.

Common sequelae for posterior uveitis include chronic cystoid macular edema, cataract, glaucoma, hypotony, phthisis, subretinal neovascular membrane (granulomas located in proximity to macula may give a rise to neovascular net and development of neovascular membranes), optic disc neovascularization (occurs in about 15% of ocular sarcoidosis patients with panuveitis or posterior uveitis), and peripapillary fibrous ring (secondary to resolved optic disc edema).

Systemic Manifestations

Skin lesions. Biopsies of these nodules reveal noncaseating granulomas.

Arthritis. Can be acute or chronic.

Neurologic signs and symptoms. About 5% of patients with sarcoidosis will have neurologic involvement, including cranial nerve palsies, neuropathy, myopathy, and aseptic meningitis.

Hilar adenopathy. Occurs in 74% of sarcoidosis patients. Splenomegaly and peripheral lymphadenopathy also occur frequently, and should be sought on physical and radiologic examinations.

Diagnosis

Serological Tests

Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels are elevated in 60% 90% of patients with active sarcoidosis. Patients previously treated with steroids may have suppressed ACE levels, thus having false-normal levels in sarcoidosis. Lysozyme levels may be also elevated, but are less specific than ACE. Elevated lysozyme levels may be found in the serum of patients with other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis and leprosy.

Radiographic Studies

► Chest x-ray

► Computer tomography of the chest is more sensitive than chest x-ray and thus may be more diagnostic for sarcoidosis.

►The gallium scan can be useful in detecting inflammation in lungs, lacrimal glands, and parotid glands.

► Transbronchial lung biopsy

► Pulmonary function tests can be used for evaluation of patients with suspected sarcoidosis. Limited diffusing capacity may be detected before the development of radiographic abnormalities on chest x-ray films.

► Tissue biopsy is required to make a definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

► The skin, conjunctiva, and lacrimal gland can be examined for possible biopsy. Positive biopsy will show noncasseating granulomas diagnostic of sarcoidosis. The incidence of positive biopsy: conjunctival is 27%55% and lacrimal gland is up to 22%.

|

|

|

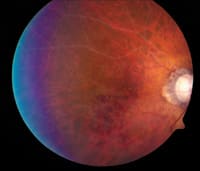

Figure 1. Ocular sarcoidosis associated with posterior uveitis. |

|

Treatment of Sarcoidosis

Major indications for therapy in patients with sarcoidosis are symptomatic pulmonary disease and uveitis. Corticosteroids remain the first line of therapy for systemic and ocular sarcoidosis. Bilateral disease most often requires systemic therapy as well. The doses of corticosteroids are adjusted based on clinical response. Patients with ocular sarcoidosis (Figure 1) may require higher daily oral doses of steroids than pulmonary sarcoidosis patients. Two or 3 high doses of intravenous pulse corticosteroids may induce a more rapid remission.

Methotrexate is being used more frequently as a steroid-sparing agent; however, it can take up to 6 months for methotrexate to become effective. Cyclosporine is being used with success in patients with ocular sarcoidosis at the NEI. Newer therapeutic modalities include daclizumab, etanercept (Enbrel), and infliximab.

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Toxoplasmosis is one of the most frequently encountered types of posterior uveitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Ocular Manifestations

With focal retinitis the active lesion can greatly vary in size, but it is commonly oval or circular and rarely bullous. New active lesions will frequently arise next to the old atrophic scars. The retina appears thickened during the acute stage and has a yellow-creamy color. The number and size of old chorioretinal scars varies from 1 or 2 small lesions to large ones that involve several clock hours of peripheral retina. Old macular scars are more suggestive of congenital toxoplasmosis than of the acquired form. Vitreous cells vary in their numbers, being denser over the active lesion. Vitreal haze and cellular reaction can be very profound and cause significantly decreased vision. Associated retinal vasculitis can be seen. As the lesion becomes less acute, the area of retinal involvement becomes less bright-yellow, more atrophic looking, and often with pigment heaping around its edges. Pigment does not surround all the old lesions, and should not be used as the sole clinical sign that detemines disease resolution.

Ocular toxoplasmosis can present in a variety of ways besides the classic manifestation:

► White punctate lesions in deep retina with little vitreous activity

► Acute retinal necrosis-like picture

► Papillitis

► Bullous lesions in retinal mid-periphery.

Immuno-compromised Patients

AIDS Patients

► Large areas of retinal necrosis

► Lesions arising perivascularly and not from old scars

► Bilateral inflammation

► Inflammation extending into the orbit and causing cellulitis and panophthalmitis.

Intraocular Surgery

► There is a risk of reactivation of ocular toxoplasmosis after cataract surgery.

► Prophylactic anti-toxoplasma therapy may be warranted.

Pregnancy

► It has been postulated that pregnancy may be a triggering factor in recurrence of ocular toxoplasmosis.

Systemic Manifestations

Immunocompetent Adults

► Lymphadenopathy in 90% of patients

► Fever, malaise, and sore throat sometimes occurring. More severe disease can occur, but is not common.

Immunocompromised Patients

► Fulminant CNS disease that is rapidly fatal.

Diagnosis

The presence of IgM titers suggests a recently acquired infection, while IgG titers are positive in reactive diseases. A negative serum titer should alert the clinician to consider other etiologies in their differential diagnosis. We feel that serolic tests should be supportive of clinical diagnosis and not definitive by themselves.

Polymerase chain reaction is becoming increasingly popular when diagnostic aqueous or vitreous taps are indicated. Intraocular IgG was found more commonly in recurrent forms of ocular toxoplasmosis than in recently acquired toxoplasmosis. However, DNA of the organism was found more frequently in recently acquired disease compared with the recurrent form.

Treatment

Our preferred initial drug regimen is: sulfadiazine 1 g taken orally 4 times a day and pyrimethamine 50 mg/d (a loading dose is usually given at the initiation of therapy) with concomitant folinic acid 35 mg 3 times/wk. Additionally we generally add 2040mg/d of prednisone, 1224 hours after initiating antimicrobial therapy. If there is an allergy or intolerance to pyrimethamine, we use clindamycin 150300 mg orally 3 or 4 times daily, or atovaquone 750 mg 3 times daily supplemented with folinic acid 5 mg every other day. For prophylaxis of recurrence of ocular toxoplasmosis, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has proven to be effective.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH AND MANAGEMENT OF PANUVEITIS

Panuveitis20-23 usually refers to uveitis that involves all of the segments of the eye. These disease entities have all the features of anterior, intermediate, and posterior uveitis combined. In this regard the features of this entity are very disease specific. In general this type of uveitis typically involves severe, sight-threatening disease. The 2 most common etiologic categories to rule out are infectious etiologies and systemic rheumatologic disorders.

Behçet's disease will be discussed as one of the systemic disorders that can cause severe, sight-threatening panuveitis. In the appropriate setting endophthalmitis needs to be ruled out. A comprehensive review of endophthalmitis will not be addressed in this review.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Behcet's disease associated with panuveitis. |

|

BEHÇET'S DISEASE

Behçet's disease is a multisystem disorder, affecting eyes that may have a devastating visual outcome. (Figure 2) This disease has a high prevalence in the Middle and Far East. Japan appears to have the highest incidence of the disease, with prevalence of 7085 cases/1 000 000 population.

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnosis of Behçet's disease is based on clinical manifestations. For the diagnosis at the NEI, we have adapted the criteria established by the Behçet's Disease Research Committee of Japan in 1974.

Recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. An almost universal finding. The lesions are usually small, painful and nonscarring.

Skin lesions. These include erythema nodosum-like lesions. Commonly seen on the anterior surface of the legs.

Acne-like lesions or folliculitis. Another common dermatologic manifestation.

Thrombophlebitis. Can be seen in the extremeties, it can be migratory, and may follow an injection or a blood draw.

Genital ulcers. May appear on the scrotum and penis in males, and on vulva or vaginal mucosa in females. Lesions can also be perianal. Genital lesions can be deep and scarring.

Ocular inflammatory disease.

Ocular Manifestations

|

|

|

Figure 3. Hypopyon uveitis associated with Behçet's disease. |

|

Ocular Behçet's disease may affect anterior and posterior segments of the eye. The disease is mostly bilateral and has a recurrent explosive course. Anterior uveitis is seen frequently with an associated hypopyon (Figure 3) in about one third of patients. Retinal involvement, which may lead to blindness is the most concerning aspect of Behçet's disease. Recurrent retinal vasoocclusive episodes may lead to macular ischemia. Bilateral central retinal vein thrombosis has been described. Areas of retinal hemorrhages and edema, with intense vitritis can be seen. The retinitis often has the appearance of a virally induced lesion. Fluorescein angiography may show areas of capillary dropout and vascular tree rearrangement. The loss of a clearly defined capillary-free zone is common.

Other Systemic Manifestations

Arthritis. Nonmigrating, nondestructive, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint. Some patients would predict an inflammatory ocular episode after their joints become inflamed.

Aortitis. Vessels of all sizes can be involved, it carries a bad prognosis. Aneurisms can occur and may rupture. Thrombosis of deep vessels, such as vena cava, may also develop.

Neuro-Behçet's. An uncommon, but grave complication. Various neurologic and psychiatric symptoms may appear. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis shows pleocytosis with predominance of neutrophils in the acute stage. Computed tomography and MRI show abnormalities in a large number of patients.

Diagnosis

HLA typing may be helpful in the diagnosis of Behçet's disease. HLA-B5, is found to be associated with the disease.

Treatment

Although initially the disease may respond to systemic corticosteroids, it becomes invariably resistant with drop in vision and the need for alternative therapeutic modalities. Our experience at the NEI has been that cyclosporine improved the visual outcomes of patients with Behçet's disease. Doses of 5mg/kg/d were found to be effective in controlling disease in 70% of patients. There is clinical evidence that supports the use of infliximab in patients with Behçet's disease. It can be given intravenously on a monthly basis. Interferon-alpha has been used with some success in various studies, but multiple side effects, such as immune reactivity, thyroiditis and retinopathy are limiting its use. Colchicine is used in Behçet's disease based on its ability to inhibit leukocyte migration. It is used mostly to prevent recurrences of the disease and not for treatment. It has been shown to reduce the incidence of genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, and arthritis. Cytotoxic agents, such as cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil have been used with varied success in treatment of Behçet's disease. Our experience has not been very promising. Severe side effects also limit the use of these drugs.

Address correspondence to: Grace Levy-Clarke, MD, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, Building 10, Room, 10N112, Bethesda, MD 20892-3655, Telephone: (301) 402-3254, Fax: (301) 480-1122, E-mail: clarkeg@nei.nih.gov

From the Laboratory of Immunology, National Eye Institute, National Eye Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. None of the authors has a financial interest in the information presented in this article.

REFERENCES

1. Bloch-Michel E, Nussenblatt RB. International Uveitis Study Group recommendations for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:234-235.

2. Nussenblatt RB, Whitcup SM, Palestine AG. Intermediate uveitis. In: Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2004.

3. Jabs DA, Johns CJ. Ocular involvement in chronic sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol.1985;102:297-301.

4. Guest S, Funkhouser E, Lightman S. Pars planitis: a comparison of childhood onset and adult onset disease. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2001;29:81-84.

5. Davis JL, Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB: Neovascularization in uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:171.

6. Prieto JF, Dios E, Gutierrez JM, Mayo A, Calonge M, Herreras JM. Pars planitis: epidemiology, treatment, and association with multiple sclerosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2001;9:93-102.

7. Malinowski SM, Pulido JS, Goeken NE, Brown CK, Folk JC. The association of HLA-B8, B51, DR2, and multiple sclerosis in pars planitis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1199-1205.

8. Silveira CM, Belfort R Jr, Burnier M, Nussenblatt RB. Acquired toxoplasmosis infection as the cause of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in families. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:362-364.

9. Melamed JC. Acquired ocular toxoplasmosis-Late onset. In: Nussenblatt RB, ed. Advances in Ocular Immunology: Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on the Immunology and Immunopathology of the Eye. New York, NY: Elsevier: 1994: pp 449- 452.

10. Mets MB, Holfels E, Boyer KM, et al. Eye manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol.1996;122:309-324.

11. Holland GN, O'Connor GR, Belfort R, Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, eds. Ocular Infection and Immunity. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby-Year Book, Inc.1996:1183-1223.

12. Friedman CT, Knox DL. Variations in recurrent active retinochoroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;81:481-493.

13. Bosch-Driessen LE, Berendschot TT, Ongkosuwito JV, Rothova A. Ocular

toxoplasmosis: clinical features and prognosis of 154 patients. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:869-878.

14. Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis in the immunocompromised host. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:399-402.

15. Holland GN, Engstrom RE, Glasgow BJ, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:653-667.

16. Moorthy RS, Smith RE, Rao NA. Progressive ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:742-747.

17. Johnson MW, Greven GM, Jaffe GJ, et al. Atypical, severe toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in elderly patients. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:48-57.

18. Labalette P, Delhaes F, Margaron F, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis after the fifth decade. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:506-515.

19. Siveira C, Belfort R Jr., Muccioli C, et al. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:41-46.

20. Mishima S, Masuda K, Izawa Y, et al. Behçet's disease in Japan: ophtalmologic aspects. Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;76:225-279.

21. Behcet's Disease Research Committee. Clinical research section recommendations. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1974;18::291-294.

22. Whitcup SM, Salvo EC, Nussenblatt RB. Combined cyclosporine and corticosteroid therapy for sight threatening uveitis in Behcet's disease. Am J Ophthalmology. 1994;118:39-45.

23. Kotake S, Ichiishi A, Kosaka S, et al. Low dose cyclosporine treatment for ocular lesions of Behcet's disease. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1290-1294.